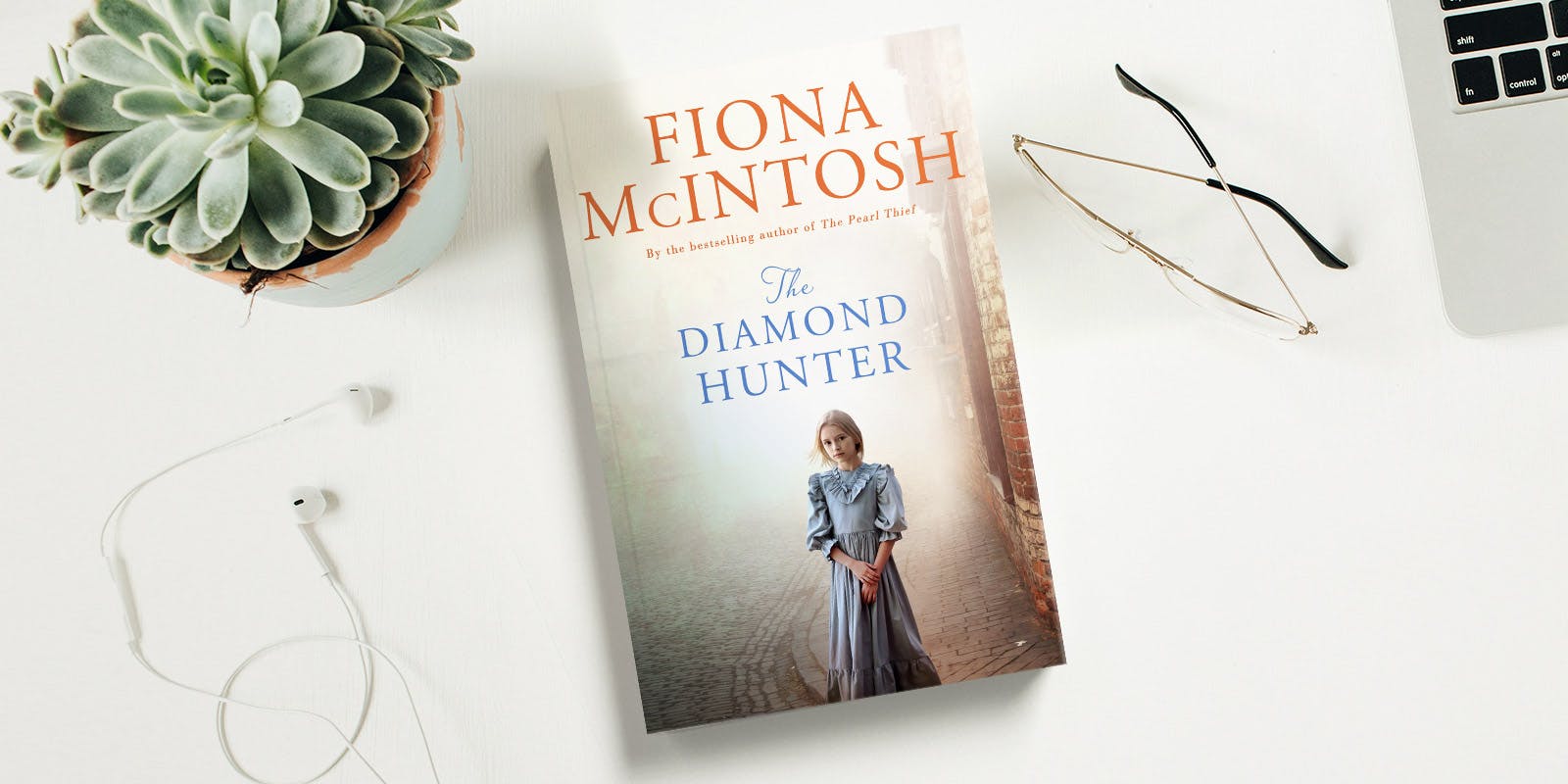

We sat down with Fiona McIntosh to hear all about bringing the 1870s to life in The Diamond Hunter.

Why diamonds?

It was a combination of elements that coalesced in a single bright moment of clarity. I was looking for a story that would follow my previous book in a wildly different way and yet would somehow complement it. The way I tackled that was to work with an entirely different era and setting to any of my previous novels while switching it up not to have a traditional love story as its core. This time I decided to have a love story around friendship. Once I’d decided how to make it different, I then began to think about how to give it some sort of pairing with the previous novel so readers would recognise it as one of mine. Given the previous book used pearls as a theme, it felt logical to continue in that vein, so diamonds roared into my mind as having plenty of potential as a match.

Around the time I was thinking this, a cousin Andrew, who had spent his entire working career with De Beers, suddenly contacted me and said let’s meet. We hadn’t seen each other for 20 years, but we organised to see one another when I returned to Yorkshire to research some final scenes for The Pearl Thief. Over an afternoon tea in the city of York, Andrew convinced me to write a book using diamonds as the premise. When he offered to meet me in Africa and open some doors into the history of De Beers and those very early days of ‘The Rush’, I found the topic irresistible.

How did you research what life was like in the 1870s?

I found this extremely challenging. Not only is this era well out of my comfort zone, but it’s not the most written about time. I struggled to find a ‘personality’ of that time and any books left me cold. I found it much easier to pack my suitcase and get myself to London to begin immersing myself in museums, libraries, galleries, homes, streets and talking to people. It wasn’t easy even then, but I did begin to get a far stronger flavour of the era, and with that came confidence. Once I landed in Africa and made the trek to Kimberley it was like being flung back in time. The museum and library there were brilliant in re-enacting those early diamond rush years, and I found it easier to absorb life as a digger once I was on location. Finding the house in Northumberland where my character’s family is situated brought their background alive for me, and that was really the turning point. Once I had Cragside under my belt as the model to use for the Grants, I was off and running. It was then a case of finding some fresh, new locations that I haven’t used in other stories that were popular in that mid to late Victorian era. It all began to flow from there, so for me, the best research was done on the run as opposed to behind my screen or with my nose buried in a research tome.

What was the most surprising aspect of your research?

So much is a surprise when you’re researching a new topic. Learning how diamonds develop, how they reflect millennia, what they look like in the rough and how clever people are in working out how to cut and polish them to their dazzling best was a wonderfully surprising education. However, I think the size and scale of the diamond mine known as The Big Hole was my great surprise. I had no idea until I stood next to it. This is the largest hole anywhere on the planet dug by hand… and it is huge. Standing above it and staring down, it’s jaw-dropping to imagine men dug this monstrous gash in the earth with little more than picks, shovels and straining muscles. When I see photographs of how it looked during the diamond mania of the late 1800s, it looks like an ant nest. People are dwarfed by its size. Learning about the rivalries, squabbles and traumas within that big hole each day as bone-weary, tired, hungry, often drunken men raced to beat their neighbour in finding the big cache… well, it’s well beyond modern understanding with all our machinery and working protocols. These men toiled all hours and they often dragged their families into the madness, which is essentially the premise of my story. Helpless wives and sisters found themselves living in a tented city with no facilities; children being born, raised, schooled in the desert with no infrastructure; and a sort of lawlessness that these pioneer places possess is hard to counter, but of course, makes for a great story.

Did you travel to research the story?

Yes, I always travel to every location for every story I write, sometimes two or three times to the same place to ensure I get it right.

For The Diamond Hunter I travelled all around London but with particular emphasis on Hatton Garden, Primrose Hill, Chalk Hill, Mayfair, and the City of London. Then I headed to Northumberland in search of one of the most important locations. For my education about diamonds, I travelled to Amsterdam and Antwerp – this is more for the modern knowledge that I needed, but I decided not to use these cities in the story. The most demanding travel I did for this book was going to Africa: first to Cape Town to learn about life as the arriving diamond rush diggers spilled off boats from all over the world and leaped onto ox wagons that would take them into the Little Karoo Desert and the alluvial deposits in and around the Boer farms that would ultimately reveal a single whopping diamond on a tiny hillock that would become Kimberley. In the time of my story it is known as New Rush. That hillock on a farm owned by the De Beers brothers became The Big Hole.

.jpg?w=690&h=344)