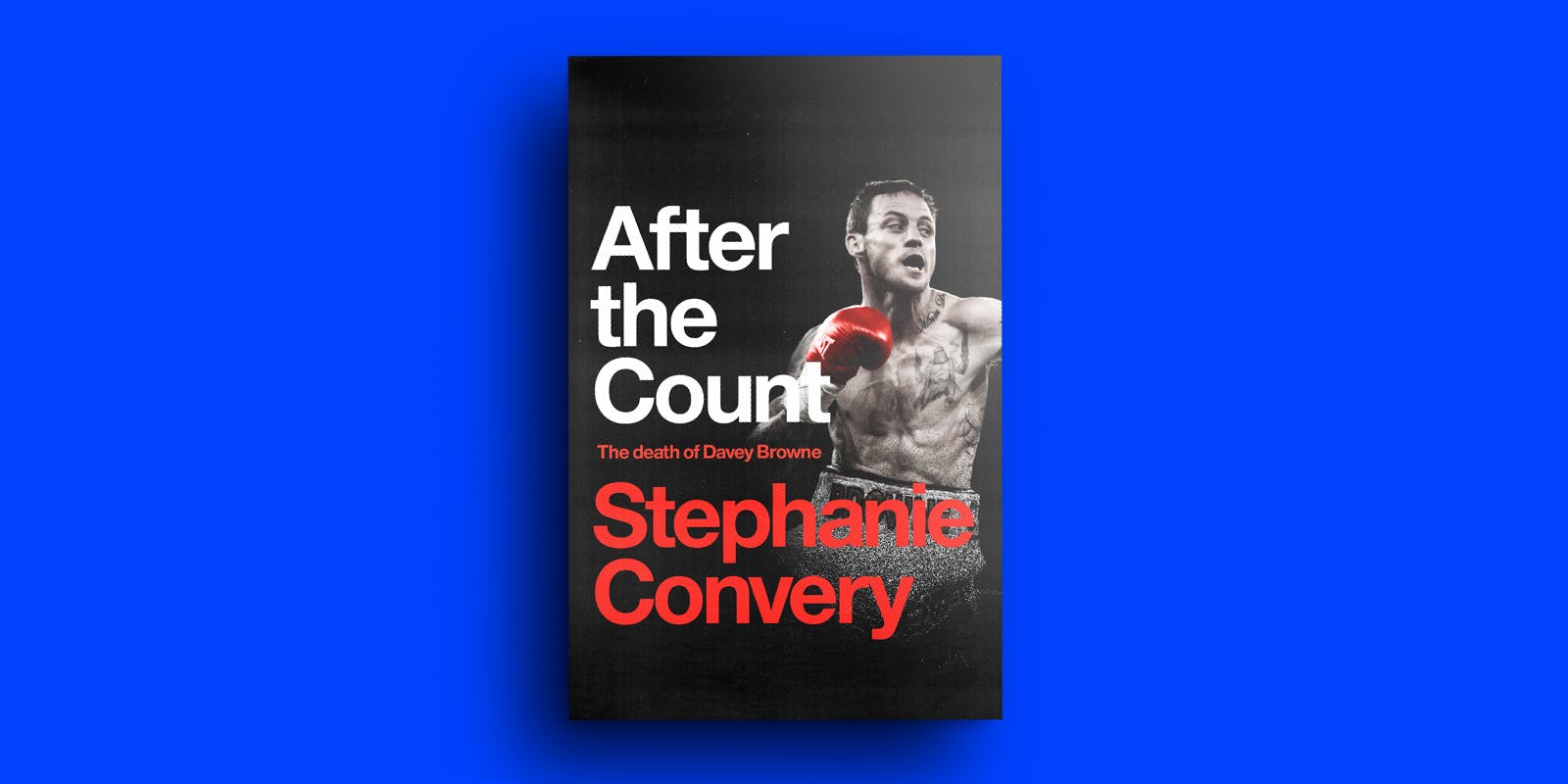

In After the Count, Stephanie Convery compares perspectives of a tragic event.

When Sydney boxer Davey Browne died after being knocked out in 2015, journalist Stephanie Convery took notice. Not only was Browne’s story compelling on the grounds of him being a young father, an up-and-comer within the boxing fraternity killed in the prime of his life. At the time Browne died, Convery herself was in training for her debut boxing contest. Her brother was also a boxer. So when questions were raised over the safety of the sport, and accountability for these rare, yet devastating, events, Convery was personally invested in finding answers.

After the Count is Convery’s exploration of what happened the night Davey Browne died. But it’s also an interrogation of boxing itself – the sport’s inherent contradictions, and the relationship between violence, masculinity and physical power. During her research for the book, Convery spoke to several attendees on the night of the fight, she attended the inquest into Browne’s death and spoke to members of his family, including his wife, Amy. In the passage below, Convery meets with the President of the Australian National Boxing Federation, John McDougall, and has a surprisingly frank conversation about the night in question, and the state of the sport in general.

John McDougall’s memory of Davey Browne’s fight accorded broadly with the story I had read in the papers – indeed, it seemed likely that McDougall had been the journalists’ primary source. He certainly had a good view: ‘I was right under Davey’s corner when he took the last blow,’ he said. Despite the way the newspapers had spun the narrative McDougall, like Amy, traced the beginnings of Davey’s disintegration in the fight at least back to the eleventh round, if not earlier.

‘Davey got hurt with a punch about the fifth round that had him in a bit of trouble,’ McDougall said. ‘But he stormed his way out of it, defended his way out of it, and for the next three rounds he come out and boxed brilliantly. And in the eleventh round he copped another one. And he did get a bit of a battering.’

What McDougall remembered as a hard punch in the fifth round, Amy remembered as a knockdown in the sixth. How our memories vary! Either way, it was clear that there had been a notable incident somewhere in the middle of the match. But that wasn’t the critical bit as far as McDougall was concerned. For him, as for Amy, the most important incident had occurred in the eleventh round, although they had different takes on how that had happened.

McDougall was working off his memory of an incident that had occurred more than a year earlier – he hadn’t seen the fight footage, and as far as he knew, I hadn’t either. He remembered Davey being escorted to the corner by the referee at the end of the eleventh round, though the video didn’t show that happening at all. But his assessment of Davey’s state seemed accurate nevertheless.

‘I think Davey was hurt,’ he said. ‘And it’s very easy to be knowledgeable in hindsight. In hindsight, the doctor should have got up and had a look of his own accord. Perhaps the referee, if he had any doubts, should have called the doctor up. But they normally only call the doctor up when there’s a cut. And the fact that Davey had fought [Magali] off before and they only had one round to go…’

There was, he seemed to be implying, ample reason for everyone involved to assume that Davey was just shaken; that he wasn’t seriously hurt and that he’d be right for one more round. It had its own kind of logic, I could see that, but it still seemed to me like a strange assumption to make, even in a boxing match, given he had just been punched off balance twice in the space of a minute.

I liked John McDougall. He was affable and open. But more than that, I also got the sense that for all the politics he must have been involved in over the years – and some of the stories that he told about the wild old days were blood-curdling – he had his own sense of what was fair and just, and whatever you thought about the details of that belief system, he was solid and unwavering within it.

And he was clearly in his element when he talked about boxing. While his stories often spiralled out widely from their point of origin, he never seemed to completely lose his train of thought. The narrative always doubled back to its original objective, and I rather got the sense that he was answering my questions via the scenic route.

We got up from the couches and made our way over to the kitchen. McDougall put the kettle on and placed a tray of sandwiches and a sponge cake on the table in front of me. It was such a disarming situation. I had never known either of my grandfathers, but I imagined that if I had, we might have done things like this – sit at a laminated kitchen table and eat sponge cake while talking about a mutual interest. Unfortunately, what John McDougall and I had in common was a man who died and the sport that killed him.

As we ate, McDougall asked me what I thought about the case, and how Amy was taking it. Conscious that the inquest was only a few days away, I didn’t want to betray her confidence: I wanted her to have her chance to say what she thought first, in court. So I stuck with generalities that I thought were honest while also fairly obvious: she had found it incredibly hard, I said, especially because the boys were small; she believed something had gone very wrong that day. My instinct was the same, I admitted, but I was trying to get all the information I could before I came to any firm conclusions.

After lunch, we headed upstairs to McDougall’s library: a stuffy, dark room absolutely packed with boxing memorabilia. It wasn’t just posters and fight cards; the man had more boxing books than I’d ever seen in one place. They lined three walls of the room, in shelves reaching to the ceiling. There were magazines, too – whole series of bound volumes. He proudly showed me his collection of autographs, including not one but three from Muhammad Ali. And lying idly on top of a pile of DVDs, as if providence had placed it there – a flyer for Davey Browne’s final fight.

It was a cheap A4 colour print job, the usual biff-ready photos of each boxer from previous fights – sweaty, beaten-up, fists aloft – cut out and pasted next to each other, separated only by those two letters: ‘VS’. The flyer incorrectly said the title under contention was for the World Boxing Council; perhaps the sanction hadn’t been secured when they started advertising, I thought. But it was eerie, catching sight of it there – it snapped me to attention, like a splash of cold water to the face.

I had one more key question for John McDougall. What did he think about the rumour that the outcome of the fight was inevitable – that Davey was going to win no matter how he boxed, because he was the local kid? That boxing was highly susceptible to corruption was well-known, but even if corruption itself wasn’t present here, it didn’t necessarily need to be. The judges and officials all knew or knew of Davey; they knew the Brownes by name if not to say hello to – in some cases, they had long personal associations with the family. How badly would Davey have had to fight to lose a match against a foreign opponent in front of people who wished him so well?

‘That’s a common train of thought in boxing worldwide,’ said McDougall: ‘You don’t get no favours in someone else’s backyard. I’ve supervised world title fights and I’ve supervised fights overseas where I’ve been totally neutral but you could see the promoter of the fight – it’s usually the promoter – is the boy’s manager as well or connected pretty close. And they bring in three judges from different countries, and they’re put up in a very fine hotel… Whether consciously or subconsciously, [that fighter] gets the benefit of any doubt. And in some cases there are some awful rorts.’

While he said he didn’t think Davey’s fight was fixed, he did think that his opponent, Magali, had been chosen so that Davey would be most likely to win the title. And the assumption that the local kid would have the upper hand was widespread enough that Davey and his corner believed it was likely that if he made it through the final rounds, he was likely to win.

McDougall was a true believer in the fight game, part of a coterie of men – and they were almost all men – that became smaller by the day. Boxing was his life, and I realised then how threatening this inquest must have seemed to him. He had watched the sport go from packing out stadiums every weekend to barely filling RSL halls. He had worked for decades to both protect and improve the sport in his home town in the ways that he believed were right. Now Davey Browne had died, and there was a real risk that the sport as McDougall knew it might be about to die too.