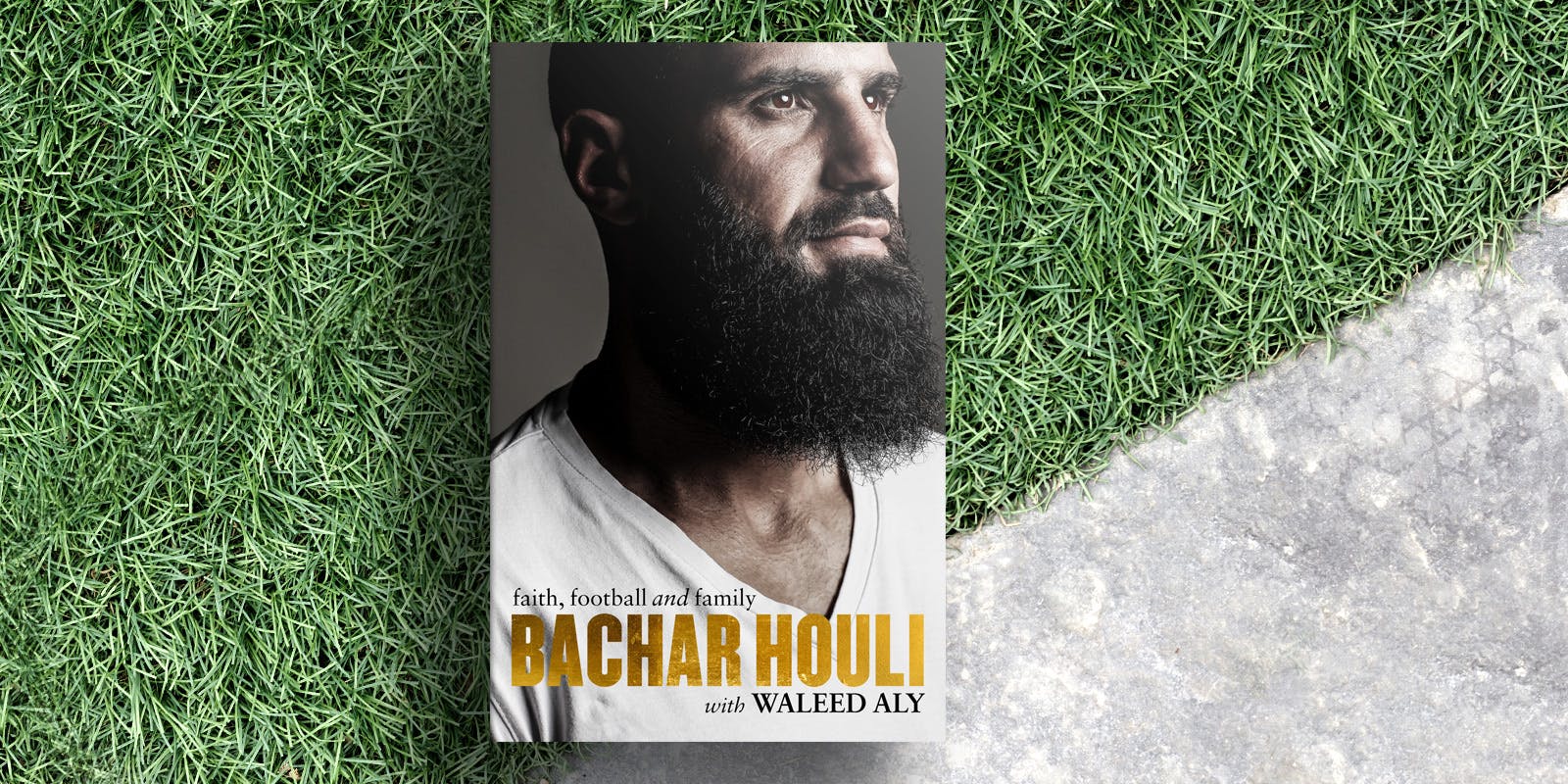

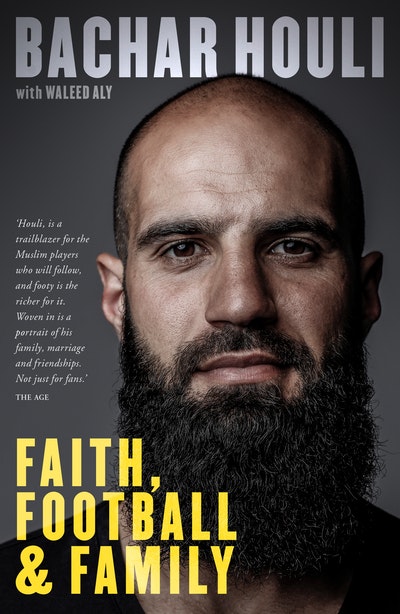

In Bachar Houli: Faith, Football and Family, AFL star Bachar Houli reveals how little by little he found his voice as an advocate for inclusion, understanding and tolerance.

‘We’re lucky he was the first,’ writes Waleed Aly in the foreword to AFL superstar Bachar Houli’s memoir, Bachar Houli: Faith, Football and Family. ‘It might have been someone less talented, someone clubs saw as too much trouble and simply discarded. It might have been someone less confident, too timid to mention those moments when football and Islamic practice intersect, leaving the next Muslim AFL player to explain why they’re raising issues their predecessor didn’t. It might have been someone less trusted and trustworthy, suspected of using a religious practice such as, say, fasting as a way of taking shortcuts with training. Or it might have been someone whose approach to Islam is less traditional, engendering an expectation that every other Muslim should be willing to make compromises.’

Perhaps the most-hyped 42nd pick of the AFL draft ever, Bachar Houli had trails to blaze. As the first practising Muslim to make the first grade, he had to teach clubs – coaches, administrators, teammates – about things like fasting and daily prayers. He had to prove to people around him that his faith was no hindrance to his football; instead, a gift. And he had to break down the media-fuelled stereotypes in 2006 of young Muslim men as terrorists and antagonistic to the Australian way of life. He did all of the above in spades. And throughout a dazzling 14-year career, which encompassed two Premiership flags for Richmond and All-Australian selection in 2019, he proved to young Muslims everywhere that being true to your identity and beliefs can be the ultimate pathway to success and respect.

‘It was destined to be Bachar,’ Aly continues. ‘He ended up exactly where he should be, where he needed to be… Sometimes it takes someone of extraordinary talent to allow their people the chance to be ordinary.’

In the passage from Bachar Houli: Faith, Football and Family below, Houli reveals an early turning point that taught him to be outwardly confident in his faith as an inherent quality of himself.

I’d always prayed as a kid, but by the time I was 14 or 15 I was taking salat [daily prayers] really seriously. I went to Werribee Islamic College, so for me – unlike for a lot of other Muslim kids in Australia – figuring out how to pray at school never presented a problem. But as I went further in football, it became clear that I’d be interacting more and more with people who’d never even seen a Muslim pray. That forced me into a position where I needed to become more confident in my faith, more ready for the questions that would inevitably come my way. The turning point happened in 2004, when I was 16.

I was captaining the under-16 Vic Metro squad in Adelaide for the national carnival, and rooming with two teammates, Daniel Beckwith and James Arundale. Previously on these sorts of tours I’d roomed with my dad, who’d take the week off work to come with me. But this time that wasn’t an option.

Daniel was a fairly quiet kid who was about my size, but James was a man-child – thickset, tall and very strong – who played the game hard. He was from the Dandenong Stingrays, so I figured he’d grown up in a pretty tough area. Above all, he was intimidating. And he was the kind of kid who was always the life of the party, who’d have the music blaring at the first available opportunity.

How was I going to pray in front of these guys? How would I even explain the basic concept to them? What possible explanation could I give for performing these strange movements which they’d probably only ever seen on some bad news story, except by connecting it to the concept of a god they probably didn’t believe in? I don’t think they even knew I was a Muslim, so I was coming from a long way back.

Our hotel room was an open space with our beds, with a bathroom attached. Salat has to be performed somewhere clean, so I could hardly use the toilet, and there were no other quiet or secluded areas I could use. The afternoon was rushing along, and it was time to pray. I was getting that feeling. Time was running out. And eventually I’d had enough. For my prayer to have any point, I knew, I needed to feel comfortable. I had to front-foot it and discuss with Daniel and James what I was about to do. So I did.

I was captain of the squad, and had been for a few years. Yet although I was never the most vocal, I had the respect of my teammates. That made the prospect of talking about my prayer with them slightly easier. But I’d also never done anything like this before. When I played club footy, my prayer ritual on match days consisted of going to that quiet spot behind the changerooms. During footy camps I’d run off into the bushes to pray. This was the first time I had no escape.

We sat on the edge of the sofa bed. Daniel was listening, but the conversation naturally went mostly in James’s direction. First I explained the basics of Islam, and eventually I got to the point of explaining the daily prayers. I told James that when I pray I need quiet so I can focus, and I asked if he wouldn’t mind turning the music down. Now I wasn’t just letting him know what I was doing – I was asking him to be quiet!

‘Do you mind us watching?’ James asked.

I couldn’t say no, so away we went. And I felt the pressure to put on a show. Make it really sincere, I told myself – which of course makes little sense, given that praying sincerely to God is the opposite of a performance for a roommate. Should I make it a long one? I wondered. Or would that make things more uncomfortable? And once I’m finished, should I just sit in contemplation for a while, or should I get up straightaway and ask James what he reckons?

In the end, I just did it. Luckily, the direction of Mecca was towards the door, not towards them. I’m not sure I had complete concentration in my prayer because I was so conscious of James and Daniel watching me.

Being watched doesn’t bother me so much now, but at the time it brought home to me just how much in life seems to be about how people see us – how obsessed we are with others’ perceptions. These days I want people to see what they don’t know: that the practice of praying is an inherently humble, peaceful one; that it’s defined by placing yourself at the lowest possible level in front of the One who is Highest. That’s who I am. That’s who we are. Our actions should emanate peace and submission. Prostration is an expression of the sincerity in a person’s heart, and points to something greater. It’s quite a thing to experience. I think that, on some level, open-hearted people pick that up.

‘That was amazing!’ James said when I had finished. ‘That was so peaceful, what you just did. Do people know about what you do?’

‘Nah,’ I said. ‘This is really the first time I’ve ever exposed what I do.’

‘Why are you shy about this?’ he went on. ‘It’s who you are! You should be proud of that. Why don’t you start teaching people this stuff? I think it’s important.’

James’s reaction is probably still the best review I’ve had. The fact that it was coming from the mouth of a 16-year-old – and specifically a straight-down-the-line, tell-it-like-it-is, rough-as-guts 16-year-old – meant that it affected me profoundly. It was a genuine turning point in my life.

Suddenly I felt confident that I could handle this from now on. And I accepted that my life was forcing me to learn more about my religion and myself. If I was going to be open about being a Muslim, I decided, I’d have to be up to the task.