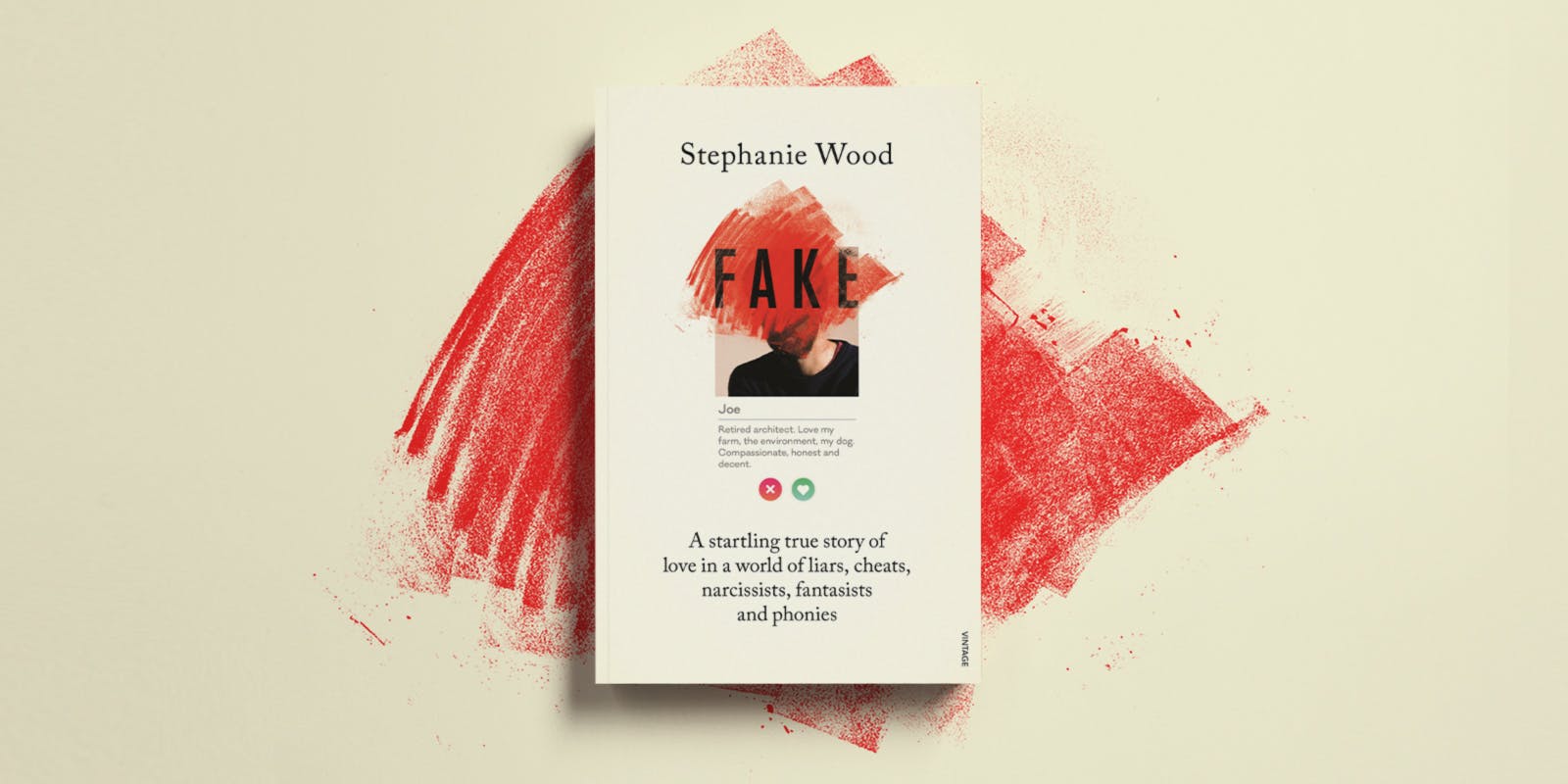

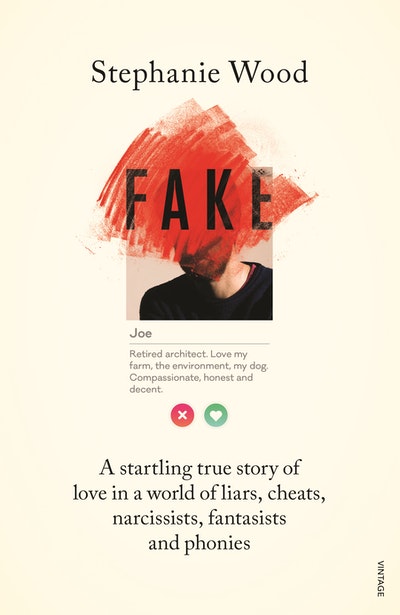

Stephanie Wood explores the pitfalls of love in an age of fakery.

Fake is journalist Stephanie Wood’s personal story of mind-boggling duplicity and manipulation. After ending a relationship plagued by frequent cancellations, no-shows and bizarre excuses, she dons her investigative journalist hat only to find that the man she thought she was in love with doesn’t exist. She also finds she is not alone; that the world is full of smart people who have suffered at the hands of people enormously skilled in the art of deception. In the passage below, she reflects on the moment the realisation of the extent of the man’s deceit hit home.

I can’t imagine it now, but in the morning I will muster the energy required to make final inquiries about the man’s story before returning to the city. At the local cafe I will have eggs for breakfast and show the owner a photo of the man. Yes, she will say, he was an occasional customer. He told her he had a farm in a different district, 50 kilometres away; she thought he was always too clean and lingered too long to be a busy farmer. I will stop by the agricultural supplies store and speak to the owner. He will not recognise the man’s face or name but he will invite me into his office and spread a detailed fire map out on his desk. He knows all the property owners in the area I explored. He does not believe the man is now, nor has ever been, one of them, he will tell me. ‘He went that far, eh?’ he will say when I tell him of the man’s stories about dorpers and native grasses. ‘You don’t fatten sheep on native grasses; farmers don’t plant native grasses.’ Besides, he will say, ‘Not many dorpers round here.’ I will tell him about the man’s lanolin-softened hands and he will cock an eyebrow. Dorpers don’t have much lanolin on them, he will say. Then I will sit in my car before leaving town and call the ringmaster’s friend, the blockie, and discover he actually owns the property with the alpacas next to the shack. I will describe the man, and the blockie’s response will be all I need to be sure, finally, that the man’s foundational story was a fabrication. Or a delusion. ‘This character was telling porky pies if he said he owned it, because he never lived next door.’

But tonight, I have no more questions in me, just an overwhelming tiredness. I return to the motel room. I put the key in the lock of my door, push it open and am hit with a cold front. I try the heater but it shudders so violently and blows out such foul dust that I abandon it. I fumble for the electric-blanket switch and lie shivering until the bed is hot and think of the warmth I’d had last time I slept here, the warmth I thought I’d finally found.

*

Among many psychological phenomena I now know about, one of the most curious is the ego defence mechanism ‘projection’. Or, as it appeared in Freud’s letters to a collaborator, projektion. It’s a complicated concept, a splitting of the self, a blame-shifting tactic. Should you possess qualities, motivations, thoughts, desires or behaviours that threaten you, or which are intolerable to have as your own, or which you can’t handle emotionally, you might deny and exile those characteristics by splitting away a part of yourself and attributing those characteristics to others. Projektion is a common behaviour of those with a weak sense of self, of the personality disordered, of narcissists.

Through the night, as I toss from one side of the vile motel bed to another, I think about projektion and the stories the man now tells himself and others about me. He has conjured up a new character for me – as a wicked woman, conniving, deceitful, delusional.

This is what he says and thinks about me: I was fired from my job. I’m obsessed with wealth. I’m blackmailing him. I siphoned money from my mother’s bank account to buy my apartment. I have a criminal history. I have periods of mania followed by despair. If I don’t take my medication, my behaviour is unpredictable. He says that I studied YouTube videos to learn how to give blow-jobs and that I’m a lesbian.

The first time I heard of what he was saying about me, my stomach twisted. Now I just laugh. It is all fake news. But for one germ of truth. Despair. That is true. In the safety of an embrace I once confided to him that I take medication for depression. ‘I thought that might be the case,’ he said, drawing me closer, tucking the information away to weaponise later.

I know now that there is in the world a silent epidemic: emotional abuse perpetrated by an army of liars, cheats, grifters, charlatans, con artists, narcissists, fantasists, flim-flam men and phonies. A disproportionate number lurk on dating websites and apps, feeding grounds for those with low instincts and impulses. Once, in an idle moment, the man observed, ‘There are so many lonely women online.’ A profusion of easy prey.

.jpg?w=690&h=344)