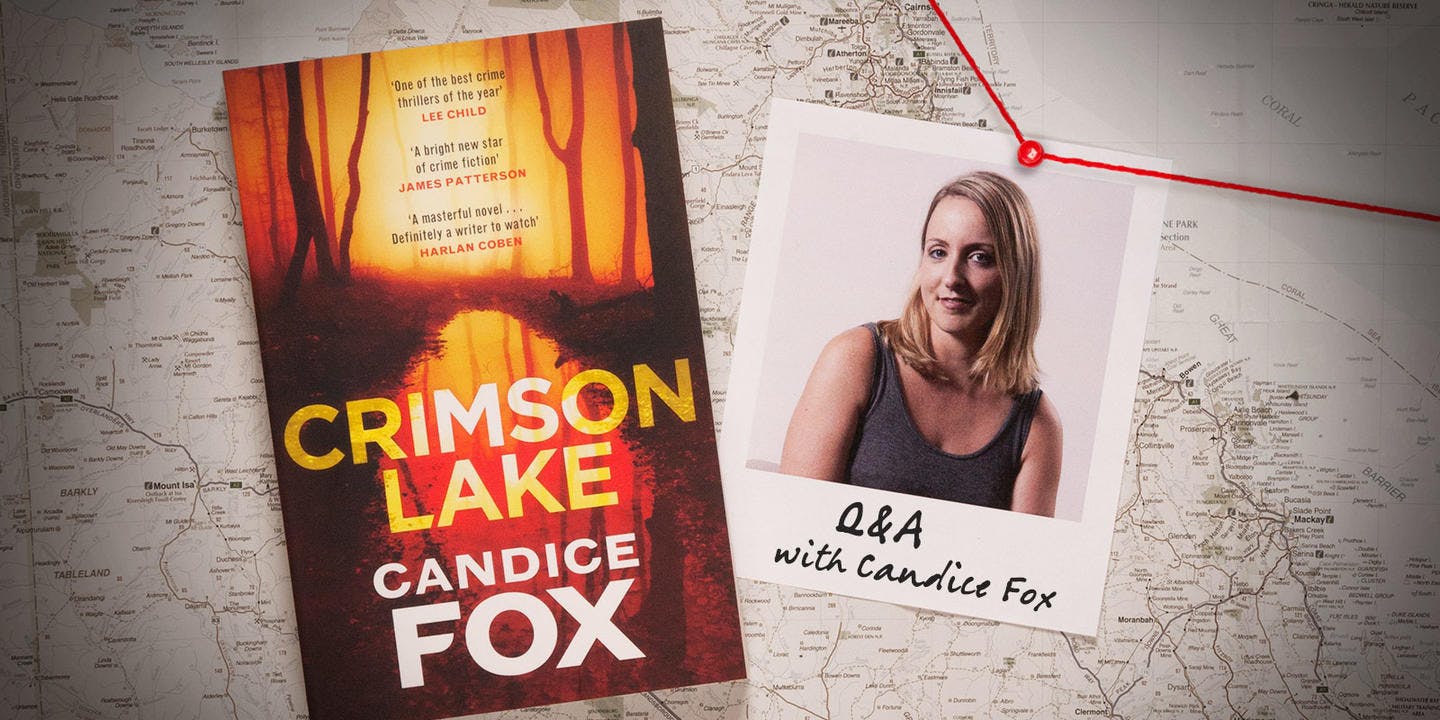

Find out what scares #1 New York Times bestselling author Candice Fox.

How and when did you discover your passion for writing?

We got our first family computer when I was twelve. It would have been around then that I started experimenting. I’d always been an intense dreamer, not particularly because I was whimsical, but I became distracted and detached very easily. My home life was very chaotic and I was deeply anxious at school, so I made up little stories to escape into. I found writing brilliant for this, because I could really hone in on my fantasy world, leave the real world altogether for long periods of a time.

Can you tell us about your childhood family life and how your upbringing may have influenced your storytelling?

I had quite an odd childhood. My mother was a devoted ‘rescuer’ of animals, trash, people. She fostered over 150 children, rehabilitated over 500 Australian native animals and was at one time writing to 20 prison inmates simultaneously. Somewhere in the midst of that I snuck around picking up tidbits of stories and trying to be front and centre for the drama.

Who are some people who’ve inspired and/or encouraged your writing practice (and how)?

I’ve studied under some incredibly generous creative writing teachers in my time. One of them was James Forsyth, formerly of the University of the Sunshine Coast. The course he took me for involved his critique and my rewriting of a manuscript ‘no more than 40,000 words’. Mine was 120,000 words, and for the entirety of two semesters he sat with me, one on one, and tore apart and rebuilt my writing.

My mother has devoured every manuscript I’ve ever written, sometimes multiple times. She never doubted my ability to get published, not once across the ten years I seriously attempted it.

What do you love about reading and writing crime fiction?

There’s a lot. One thing could be, I think, that there’s nothing subtle about what’s at stake in this genre. I don’t mean to pick on romance, but often in romance there are multiple subtle questions at the forefront: Will they get together? Are they right for each other? Who are they both, really, deep down inside? I like direct, hard-hitting, explicit stakes. Will they catch him before someone else dies? Will the bomb go off? Will she escape the killer’s lair? The subtle, deep, emotionally tumultuous questions are woven in and around these ball-breaking ones taking centre stage.

To what lengths do you research to create authentic characters and places, and believable cop and crime dialogue?

Believe it or not, it’s difficult to research in this genre without coming off as a psycho, particularly with primary sources. I’m not a psycho – but can I tour your morgue? I’m not a psycho – but can you tell me about that abduction case you were on? I’m not a psycho – but can I ask you about cyanide poisoning? Certainly it’s gotten easier since I’ve been able to flash my credentials around as a multi-published author. My recent chats with ex-army guys about IEDs raised few eyebrows.

What compelled you to write Crimson Lake?

I started thinking about it all around the time that Hey Dad! actor Robert Hughes began facing allegations in the media about sexual assaults on young girls. Before I’d read past the headline I thought ‘That’s it for him.’ It struck me that suspicion of pedophilia, even if it’s never proven, even in some cases if it’s proven false, never goes away. You can’t forget a thing like that about a person. It stains. And thinking about it further, I realised that the accusation of murder holds the same power.

The opening sentence of Crimson Lake – ‘I was having some seriously dark thoughts when I found Woman’ – sets the tone for the book in several ways, and offers up a bunch of questions. (What is the nature of these dark thoughts? Is our narrator capable of dark actions? If so, how can we trust that he’s not capable of the horrific acts of which he’s been accused? Who is Woman?) How important is this sentence in the bigger picture of the story? And at what stage in the writing process did you know you had it right?

There’s rarely much of a change in my opening scenes, because by the time I start a book I’ve usually thought about it for months at a time, and I’m writing confidently, excitedly, in the beginning. Ted’s accusation is right up front in the novel, and these dark thoughts he’s having are tangled up with his saviour of the goose and her babies. I wanted Ted to be very likeable, so that these dark thoughts and dreams he experiences really confuse and unsettle the reader. You can’t trust Ted. But you want to. And I was very interested in that feeling and its ability to push a reader through the pages quickly as they search for a resolution.

What compelled you to write a sequel to Crimson Lake?

I’d actually begun a forth Bennett/Archer book when my agent called and asked if I might consider writing a second in the Conkaffey/Pharrell series. Crimson Lake made such a splash, multiple publishers had asked for another one. I think if I hadn’t been asked, however, I might have returned to the story anyway one day because I was curious myself about how Ted was going to keep pushing on in his life after such a devastation.

Redemption Point starts with a line that captivates the reader immediately: ‘There were predators beyond the wire.’ How did you come up with this line?

I think it might have popped up during the re-work, but the concept for the starting point was always the same. I think it’s critical that the first line of any book contains a problem, a disorder of some kind, and you’ll see that almost all the classics adhere to that rule.

Are there other authors, artists, books, films etc that you look to for inspiration in capturing the eeriness of Australian settings?

I set out in Crimson Lake to capture the kind of atmosphere the writers of True Detective portrayed so wonderfully in their first series. They were writing about Louisiana, but having spent some time in Louisiana myself I saw plenty of parallels between it and Cairns. It has always struck me that Australian crime fiction is overloaded with stories set around the glittering Sydney Harbour, and while that’s fine (hey, my Bennett Archer series begins there), there are amazingly diverse settings in this country that a global audience ought to experience.

After visiting the darkest places of the minds of imperfect, often damaged, people, how do you go about snapping back into everyday life? Do you feel affected by your creations?

I guess I’m affected by what I do for a living, but not in a negative sense. Writing books is all I do for a living at the moment, so I spend seven or eight hours a day with my characters. In that way, it’s hard not to let them come wandering into my everyday life. I see people who look like them sometimes, or I hear a song that I know one of them in particular would like, and all of a sudden I’m thinking about them like they’re real people. That’s weird. But I’m not lying awake at night tossing and turning over someone’s gruesome death or anything like that. People have got to die in my books. It comes with the territory.

How deeply have you explored the psychology of criminality in order to understand the motivations of people capable of horrendous things?

Crime is essentially the centre of my life – it’s all I read about, it’s what I teach (when I have time to teach, which is rare these days). I listen to true crime podcasts while I do the washing up and I watch crime docos on my lunch break. With that comes a lot of understanding of the psychology, because more often that not these programs are as interested in telling you what happened as telling you why. The first questions I ask myself when I start planning a novel are ‘Who’s killing who?’ and ‘Why?’, so the more diverse the psychology of the acts I research, the better for me.

What scares you?

I’m incredibly difficult to scare or disturb in any way, which is hard for me, because I really enjoy scary movies. Very rarely over the last few years have I watched a scary movie without becoming bored. And while people are often shocked and moved by terrible news stories, I can either think of something I’ve seen that’s worse or I’m more curious than scared. Be warned! This gig will desensitise you!

How do you reading habits change when writing crime?

I certainly read a lot slower when I’m writing, because by the end of the day I’m seriously tired of looking at words. I can take a month or more to get through a single paperback and I often start and don’t finish books. I only read crime or true crime – I can’t maintain my interest in any other genre.

What do you think is the scariest book you’ve ever read?

I read O.J. Simpson’s If I Did It, and found it to be one of the more shocking examples of how convincing and manipulative pro-social psychopaths can be.

What’s a book you return to time and time again, and why?

Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein. It’s a beautiful telling of something I think everyone has experienced; the sheer terror of creating something and watching helplessly as it grows and twists out of your control.