Advancement of women doctors: one of very few unexpected silver-linings of war.

Whether it was the allure of travel and adventure, the opportunity to roll up their sleeves at the forefront of their medical fields, or just plain fear of missing out – Australian women doctors were caught up in the same contagious magnetism of World War I as their male colleagues. And with pre-war social mores loosening, the War presented opportunities for women to seize control of their own destinies. Around two dozen Australian women doctors headed to Europe and Africa.

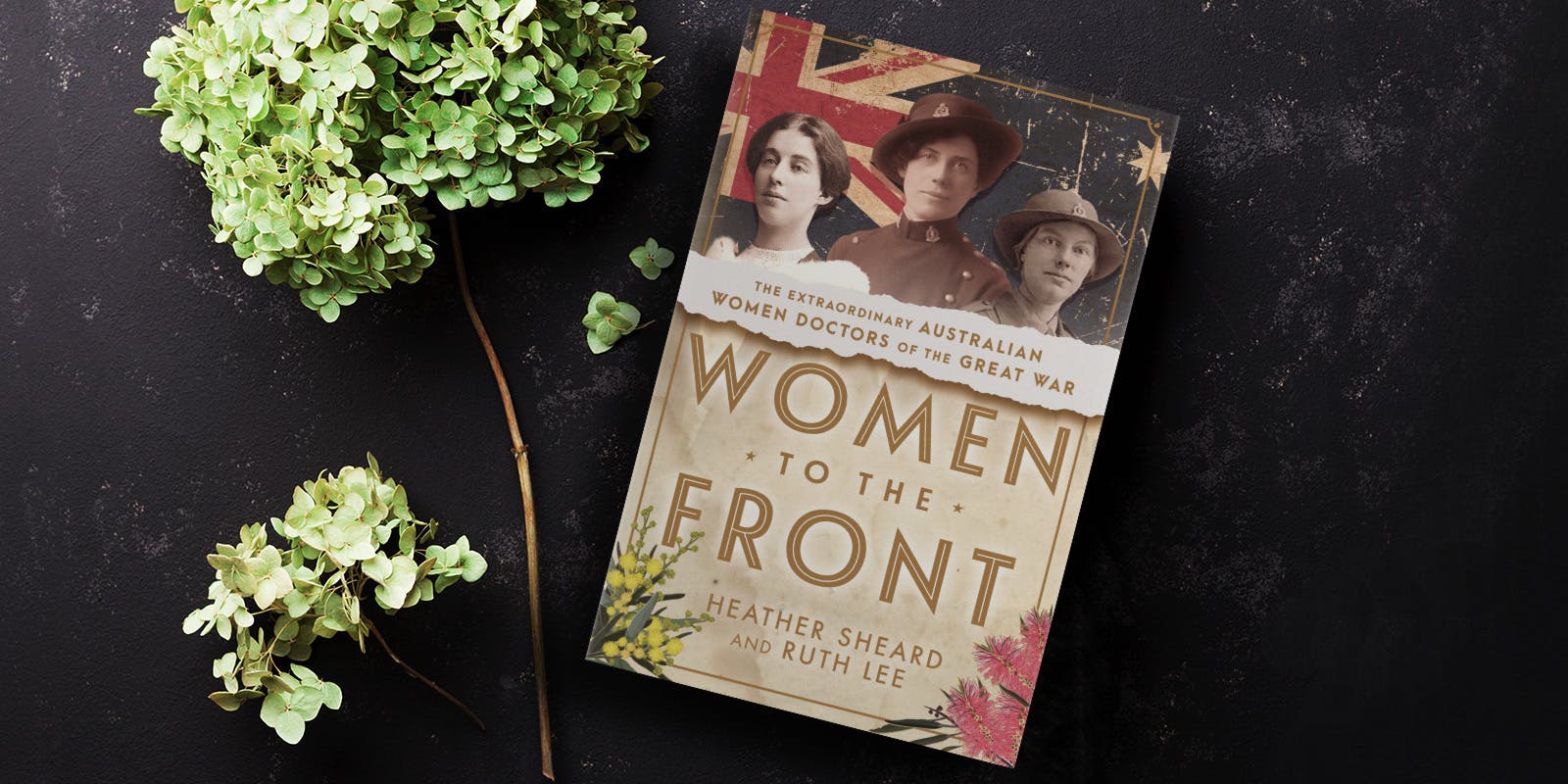

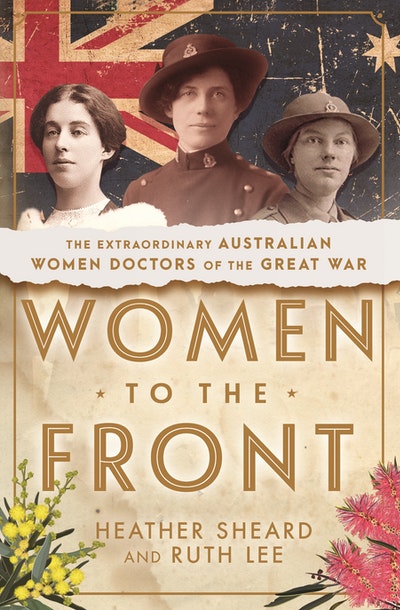

By sharing the stories and experiences of the women who served as doctors during the Great War, Heather Sheard and Ruth Lee’s Women to the Front honours the contribution these remarkable women made. In the passage below, they introduce how the necessities of war allowed female doctors and surgeons a boot in the door.

World War I, known at the time as the Great War, was a humanitarian crisis of massive proportion. Lethal new technology that killed and wounded people en masse joined with pandemic infections producing unprecedented loss of life and terrible affliction. Hundreds of thousands fled, carrying disease with them while also encountering new ones. Life in the war years was outside everyone’s previous experience and this unexpectedly allowed women to circumvent some of the barriers faced pre-war; but not without a struggle.

When the German army marched into Belgium in August 1914, Melbourne doctor Helen Sexton went straight to the British War Office (WO) in London to offer her services to the Royal Army Medical Corps (RAMC). At the time, 129 women were registered as medical practitioners in Australia with around 1000 medical women in Britain, and many wanted to serve. For military officialdom, however, the notion of women doctors serving on the battlefield was outrageous. The answer throughout the British Empire was an unequivocal ‘No!’. Women doctors were not required for the war effort and advertisements were taken out to that effect in the newspapers.

But these were women accustomed to discouragement and to the denial of their professional capabilities. With routine determination and practised agility, at least twenty-six Australian women doctors ignored official military policy and served as surgeons, pathologists, anaesthetists and medical officers between 1914 and 1919. They served in Great Britain; on the Western Front in Belgium and France; on the Eastern Front including Serbia, Macedonia, Montenegro, Greece, Galicia and Russia; on the hospital island of Malta; and in Egypt and Palestine. Women to the Front is their story.

Women had pried open the doors of Australian medical schools twenty-five years before, with the first medical women graduating in 1891. Highly motivated and self-confident, they nevertheless needed a thick skin to succeed in qualifying and practising as doctors. Initially they had few role models and their experience at university and in postgraduate attempts to gain professional standing had deepened their feminist ideas and commitment to each other. However, in 1914 the acceptance of women into the medical profession remained tenuous. Their access to hospital residencies and the development of specialist medical skills, such as surgery, was extremely limited. In Melbourne this led to the creation of the Queen Victoria Hospital in 1896 for the provision of women doctors for women patients but also to provide valuable clinical experience for women doctors. Most practised within the sphere of women’s and children’s health and were referred to as ‘lady doctors’. And ‘lady doctors’ did not go to war.

Yet the Great War’s unrelenting need for medical services would clear the way for women doctors. Medicine was essential to war; it took centre stage in emergency treatment, in healing the wounded and sick, in health and hygiene for the armed services and in dealing with the dead. English doctor Flora Murray said that in August 1914, ‘women doctors knew instinctively that the time had come when great and novel demands would be made upon them, and… an occasion for service was at their feet’.1 Like their British counterparts, many Australian medical women saw the war as an extraordinary opportunity to validate their professional status by demonstrating their competence alongside their male peers in war.

Given the official discouragement, why did Australian women doctors want to go to war? Much of their motivation was the same as that of their male colleagues. They had been educated from childhood in a curriculum steeped in the centrality of the British Empire, its history and culture, and the need to contribute to the Empire’s war effort was self-evident. They believed that it was their duty to use their medical training and experience to alleviate suffering, including on the battlefield. It is hardly surprising that many women wanted to share the patriotic burden of World War I with their brothers, fathers, uncles and fiancés serving overseas. The war provided a context, although a tragic one, of intensive clinical practice for medical personnel, and over its course ensured their exposure to the latest developments in medical research: infection control, blood typing and transfusion, the use of X-ray technology and new methods for saving damaged limbs. The chance to use and improve their medical skills was a professional opportunity that women doctors did not want to miss.

1. Murray, Flora, Women as Army Surgeons, Hodder & Stoughton, London, c. 1920, p. 4.