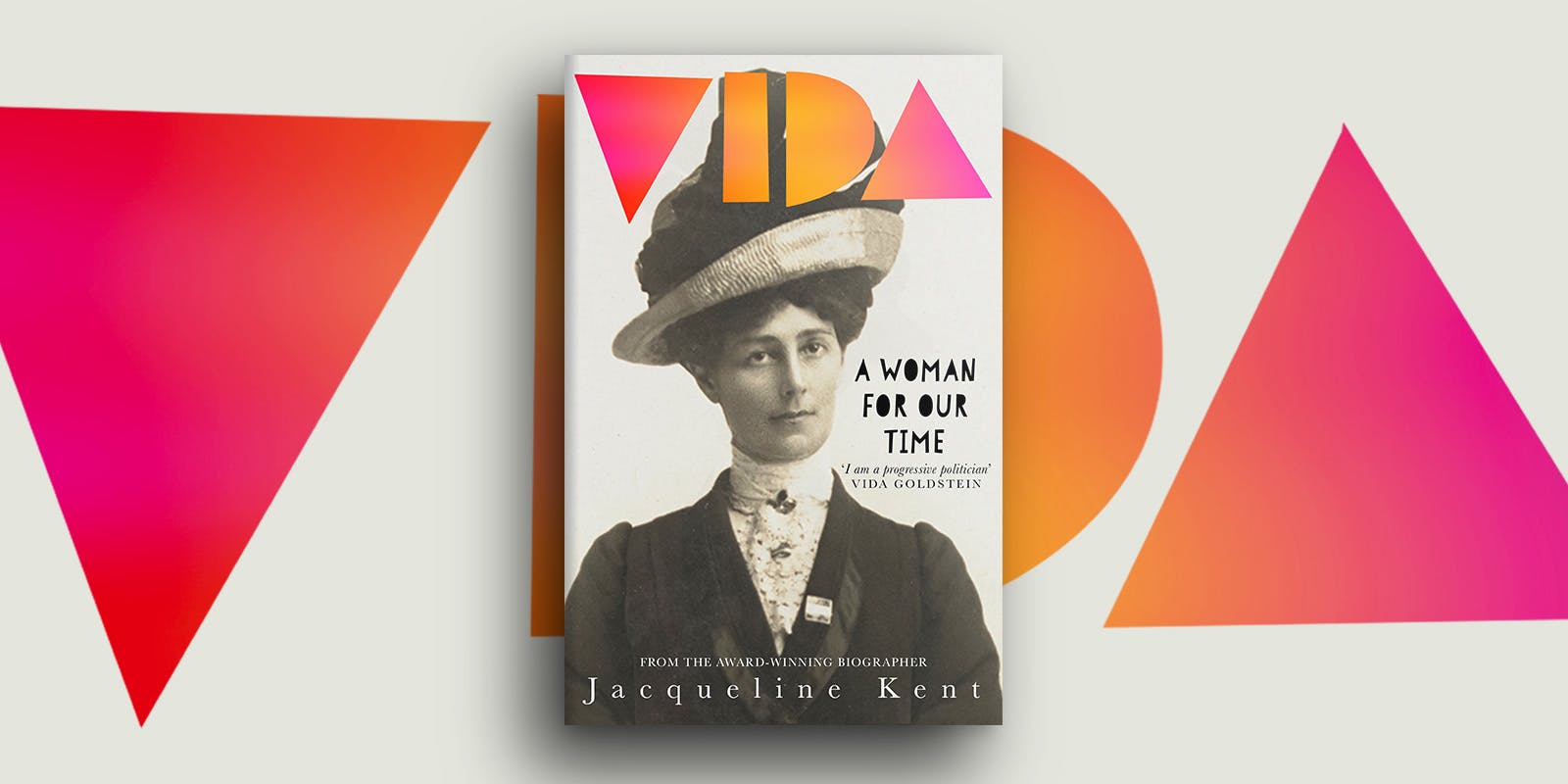

Jacqueline Kent on the inspiration behind her book about an extraordinary woman, Vida.

How did I find out about Vida Goldstein? As sometimes happens in these cases, it was because of a friend. Dianne Takahashi, then Dianne Scott, told me years ago that she had written her University of Sydney history honours thesis about Australia’s suffragettes. I knew about the Pankhursts in England, but had no idea we’d had any ourselves. From Dianne, I learned that Vida Goldstein (1869-1949) was in the forefront of the suffrage movement, and had been the first woman in the Western world to stand for a national parliament – in Victoria, for the Senate, in 1903. Why. I wondered, hadn’t anyone heard of her?

Dianne and I put together a radio documentary about Vida and her life for an ABC program called The Coming Out Show. I did the writing, Dianne the research. In those days, at the time of second-wave feminism, ‘coming out’ had connotations different from today’s: it meant women storming the barricades, making their voices heard, standing up to be counted. The producer of the program was Julie Rigg, a celebrated feminist and journalist who later became a well-known film reviewer for the ABC. Dianne and I thoroughly enjoyed preparing our half-hour feature: Vida was such a vital, humorous and intelligent woman, and there were so many wonderful quotes about her, as well as her own often witty comments.

Fast forward to 2017. I had published a biography of Julia Gillard and my head was still full of the fortunes of Australian women in politics. Writing about Vida, such a pioneer, seemed an obvious next step. It was equally obvious that a book about Vida’s life should be dedicated to Dianne.

I didn’t want my book about Vida to be simply an account of what she did when: she has already been given that kind of biography, That Dangerous and Persuasive Woman by Janette Bomford, published in the 1990s. As well as telling Vida’s life story I wanted to do find parallels, if any, between her experience of political life and that of the women who succeeded her, right up to the present time. How, if at all, had things changed for political women in the last 120 years?

I did not have to look far to discover similarities between Vida’s experiences and those of the women who followed her. Some men’s reactions to women seeking political power, for instance. The views of some women about their ambitious sisters, too. And even the way political women were reported in the newspapers – from the beginning, journalists have preferred to comment about women candidates’ clothes rather than what they actually said; the journey between Vida’s ‘coquettish millinery’ and Julie Bishop’s high-heeled red shoes sometimes seemed depressingly short. And when Julia Gillard made her scathing misogyny speech in 2013, Vida would certainly have been cheering her on.

I spent two years on research. It would have taken me much longer without two key resources: Trove, the wonderful treasury of Australian newspapers digitised by the National Library of Australia; and Vida’s papers from the London Women’s Library, available via Dropbox. O brave new digital world! In Vida’s time reporters took down political speeches verbatim, presumably in shorthand, and Vida’s words occupied many column inches, giving me a very good idea of her clarity, wit and logical common sense. Commentary or analysis about her views was in much shorter supply: perhaps in those days newspaper readers were being encouraged to make up their own minds.

I knew Vida had tried to enter Parliament no less than five times, with a lot of work necessary for each attempt, but I was delighted to find out how much more she had done. Particularly interesting, I thought, was her work during World War I. She stood for parliament as an independent pacifist at a time when the whole country, it seemed, was wildly in favour of ‘our boys’ fighting for Britain against Germany, despite the slaughter of the Western Front. Vida set up the Women’s Peace Army and she and her colleagues addressed thousands of people at rallies, handed out anti-war pamphlets and wrote articles condemning the war. She stood against the Australian Government when PM Billy Hughes arranged to legislate conscription for overseas service. The parallels with the work of anti-war activists during the Vietnam conflict are easy to find.

Vida was so brave. She was ridiculed, shouted at, attacked – several times returned soldiers set fire to the stage she was speaking from – and was in actual physical danger more than once. Not only did she calmly continue to present her anti-war message but she organised food and other supplies for women and children who were struggling financially while their men were away at the war. Vida also proposed and supported a wide range of legislation to benefit women and children, as well as male workers, and she helped set up Victoria’s first hospital by and for women.

She never wavered from her belief in feminism as a means of achieving a just world. And so the subtitle of my book ‘A Woman for Our Time’ is, I think, highly appropriate. All the way through the research and writing of Vida’s story I felt a real comradeship with her: her struggles, her victories, her attitudes and convictions – all recognisable, all easily understandable for a twenty-first-century audience.

Vida Goldstein is one of Australia’s many previously unsung heroines. I hope readers will like, appreciate and admire her as much as I have done.