- Published: 15 September 2020

- ISBN: 9780670079490

- Imprint: Viking

- Format: Trade Paperback

- Pages: 352

- RRP: $34.99

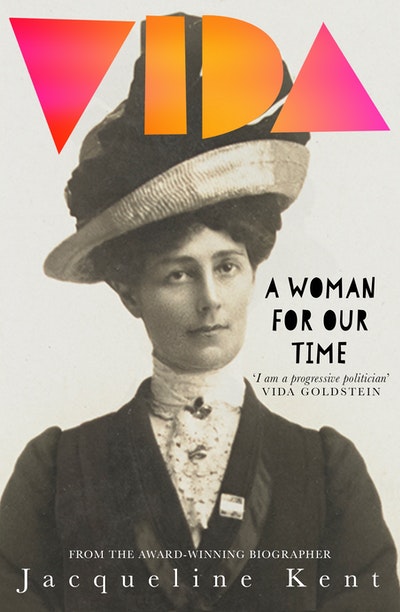

Vida

A woman for our time

Extract

INTRODUCTION

Melbourne, 1912: on the busy corner of Collins and Swanston streets stood an attractive woman of middle age. She wore a long dark skirt, neatly fitted jacket, white blouse and a wide-brimmed, fashionable straw hat. In her right hand she held a tabloid newspaper called Votes for Women; in her left another, the Woman Voter.

The businessmen, women and children hurrying to escape the threat of April rain could hardly believe their eyes. Everybody in the city was used to seeing young street boys, copies of The Age and The Argus tucked under their arms, dodging across the cable tram tracks, touting their wares in shrill, birdlike voices. But a woman selling newspapers? It was little short of scandalous. Nice women simply did not flaunt themselves in public in such a way. Even worse was the kind of paper this woman was selling. Some passers-by might have heard of Votes for Women, the tabloid published by the English suffragettes as part of their campaign to be given the vote. Fewer knew about the Australian version, the Woman Voter. But those who did – and they were mostly middle-class, progressive women living in Melbourne – would have recognised its publisher, and the seller, immediately, for she was a celebrity.

Vida Goldstein was the first woman in Australia – indeed, the first woman anywhere in the Western world – to stand for election to a national parliament. Depending on people’s political beliefs, this branded her as either a shameless hussy and a member of the ‘shrieking sisterhood’, or a heroine. Her gruelling campaign for a seat in the Senate in 1903, though unsuccessful, had garnered her headlines, and not simply in the country of her birth: in the United States and in England she had also been widely celebrated. Indeed, Vida counted almost every prominent feminist in Australia, Britain and the United States as a friend.

On that April afternoon, a close observer might have noticed that, despite her usual appearance of calm, Vida was looking anxious. She had told herself it was ridiculous to be so nervous: after all, she had spoken in front of thousands of people in London’s Royal Albert Hall, and what could be more frightening than that? But there, as at the dozens of other meetings she had organised and speeches she had given, she had been surrounded by supporters. And though she had been verbally abused occasionally – and had given as good as she got – standing alone on a busy city corner was a very different thing. Here, she was vulnerable to direct attack.

Vida knew that Votes for Women was not a popular periodical. Supporting English women in their struggle to gain the vote – the right their Australian sisters already had – provoked hostility in staid Melbourne. In letters to the editor of The Age and The Argus, citizens asserted that women had no business smashing windows or otherwise destroying property simply because they claimed this right. They believed the suffragettes should follow the example of Australian women: wait until men granted them the suffrage. From her own experience Vida knew how effective that was likely to be, and so she had resolved to do what she could to draw attention to their plight. Even some of her colleagues did not quite understand why she was so vehemently in support of the English suffrage. But for years Vida had devoted herself to the cause of social justice, wherever she thought a fight was necessary.

The other newspaper she held out for sale, the Woman Voter, was her own project. She was its publisher, owner and chief editor, and she had set it up to show Australian women what a weapon their newly granted vote could be if they worked together for the common good. The monthly paper was not simply polemic, not just parochial in scope: Vida published stories and articles by women from the USA and Britain, interviewed prominent women in many fields, and provided reports on women’s status from all over the world. Crisply written, free of the cooking and fashion hints characteristic of other publications for women, the Voter was the forerunner of New York’s Ms. magazine that appeared fifty years later at the height of second-wave feminism.

In the two hours before dusk, people streamed past Vida on her corner – some amazed, some amused, a few openly contemptuous. She was laughed at, glared at; one or two passers-by smiled and nodded encouragingly. But nobody bought either paper. Then came a woman heavily laden with parcels, who stopped in front of her. ‘Will you buy our non-party women’s paper, price one penny?’ asked Vida. The woman smiled, set down her parcels on the pavement, dived for her purse and handed the coin over in exchange for a copy of the Woman Voter. ‘My first buyer!’ wrote Vida later. ‘I felt inches taller.’1

But the woman was almost the only buyer that day, and one of only a handful for the next few days. Then Vida hit upon a bold idea. In Chapel Street, Prahran, she pinned a poster to her skirt that read VOTES FOR WOMEN TORTURE! BY ORDER OF THE HOME SECRETARY. This stark description of what was being done to the suffragettes in England caused a sensation, and all her copies of both newspapers sold out immediately. Vida’s photograph appeared in the local press – it remains the most famous photograph of her – and there were no more sneering remarks, no more supercilious glances from passers-by. Within a couple of weeks, following her example, eight women were selling her papers on the streets of Melbourne.

How did Vida Goldstein, a woman in her forties, the child of an impoverished immigrant father and a mother whose family was blighted by tragedy, develop the kind of courage that enabled her to do this?

Vida was born thirty years before Federation; she died four years after the end of World War II. She came to adulthood when Australia was in the throes of inventing itself as a united nation, where ways of doing things – good and bad – existed to be tried, adopted or rejected. She was and remained vitally interested in social justice issues for women and children everywhere. She was an incisive and shrewd commentator on international politics and her writings on any subject are logical, clear, sometimes humorous and always full of energy. She was also a forceful and persuasive orator, with a natural authority that enabled her to be heard at a time when microphones did not exist. (It’s a lasting regret of mine that her voice, always described as low and well modulated, was never recorded for posterity.)

It’s not as if Vida herself has been entirely neglected: she is at least briefly mentioned in almost every history of women in Australia. All the same, her name is not particularly well known outside scholarly circles. The question then becomes: given the kind of influential person she was for so many years, given all the things she achieved, why haven’t we heard more about her?

This book is an attempt to answer that question. Among other things, it looks at the forces, social and political, that catapulted Vida to fame and as swiftly turned away from her. It examines the steadfast beliefs that guided her – sometimes to her detriment – and her unswerving devotion to her ideals, despite the prejudice she had to fight throughout her public life. And in describing Vida Goldstein’s extraordinary life and work, this book honours the phalanx of equally determined, intelligent women who stood with her. Above all, it seeks to show how much Vida was not simply a woman of her times, but someone whose views and beliefs are refreshingly contemporary – and so who is equally a woman of our time.

1 Woman Voter, May 1912

Vida Jacqueline Kent

Vida Goldstein was an advocate for women's rights, a campaigner for peace, fought for the distribution of wealth, and a trail-blazer who provided leadership and inspiration to innumerable people.

Buy now