- Published: 3 August 2021

- ISBN: 9781529112313

- Imprint: Vintage

- Format: Paperback

- Pages: 280

- RRP: $22.99

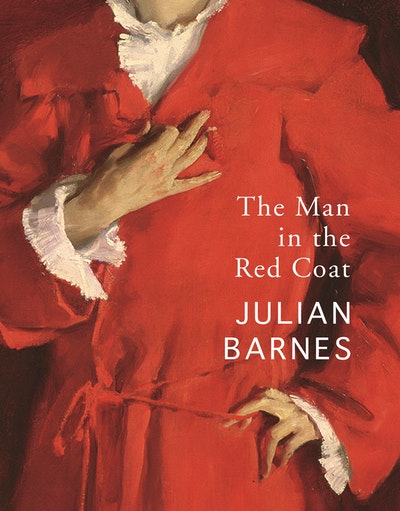

The Man in the Red Coat

Extract

We might even begin across the Atlantic, in Kentucky, back in 1809, when Ephraim McDowell, the son of Scottish and Irish immigrants, operated on Jane Crawford to remove an ovarian cyst containing fifteen litres of liquid. This strand of the story, at least, has a happy ending.

Then there is the man lying on his bed in Boulogne-sur-Mer – perhaps with a wife beside him, perhaps alone – wondering what to do. No, that’s not quite right: he knew what to do, he just didn’t know when or whether he would be able to do what he wanted to do.

Or we might begin, prosaically, with the coat. Unless it is better described as a dressing gown. Red – or, more exactly, scarlet – full length, from neck to ankle, allowing the sight of some ruched white linen at the wrists and throat. Beneath, a single brocade slipper allows tiny dashes of yellow and blue into the composition.

Is it unfair to begin with the coat, rather than the man inside it? But the coat, or rather its depiction, is how we remember him today, if we remember him at all. How would he have felt about that? Relieved, amused, a trifle insulted? That depends on how, at this distance, we read his character.

But his coat reminds us of another coat, painted by the same artist. It is wrapped around a handsome young man of good – or at least prominent – family. Yet despite standing for the most famous portrait painter of the day, the young man is not happy. The weather is mild, but the coat he is being asked to wear is of heavy tweed, intended for an altogether different season. He complains to the painter about its choice. The painter replies – and we only have his words, so cannot tell the tone on a scale from gently teasing to professionally commanding to magisterially contemptuous – the painter replies: ‘It’s not about you, it’s about the coat.’ And it’s true that, as with the red dressing gown, the coat is now remembered more than its young inhabitant. Art outlasts individual whim, family pride, society’s orthodoxy; art always has time on its side.

So let’s continue with the tangible, the particular, the everyday: with the red coat. Because that’s how I first encountered the picture and the man: in 2015, hanging in the National Portrait Gallery in London, on loan from America. I called it a dressing gown just now; but that’s not quite right either. He hardly has pyjamas underneath – unless those lacy cuffs and collar were part of a nightshirt, which seems unlikely. Do we call it a day coat, perhaps? Its owner has hardly just fallen out of bed. We know that the picture was painted in the late mornings, after which artist and subject had lunch together; we also know that the subject’s wife was astonished at the painter’s large appetite. We know that the subject is at home, because the picture’s title tells us so. That ‘home’ is expressed by a deeper hue of red: a burgundy background setting off the central scarlet figure. There are heavy curtains tied back by a loop; and a further, different swathe of fabric, all of which melts into a floor of the same burgundy colour without any obvious dividing line. It is all highly theatrical: there is swagger not just in the pose but also in the pictorial style.

It was painted four years before that trip to London. Its subject – the commoner with the Italian name – is thirty-five, handsome, bearded, gazing confidently over our left shoulder. He is virile, yet slender, and gradually, after the picture’s first impact, when we might well think that ‘it’s all about the coat’, we realise that it isn’t. It’s more about the hands. The left hand is on the hip; the right hand is on the chest. The fingers are the most expressive part of the portrait. Each is articulated differently: fully extended, half-bent, fully bent. If asked to guess the man’s profession blind, we might think him a virtuoso pianist.

Right hand on chest, left hand on hip. Or maybe something more suggestive than this: right hand on heart, left hand on loins. Was that part of the artist’s intention? Three years later, he painted a portrait of a society woman that had a scandalous effect at the Salon. (Could the Paris of the Belle Epoque be shocked? Certainly; and it could be just as hypocritical as London.) The right hand plays with what looks to be a toggle fastening. The left hand is hooked into one of the coat’s twin waist cords, which echo the curtain loops in the background. The eye follows them along to a complicated knot, from which dangle a pair of feathery, furry tassels, one on top of the other. They hang just below groin level, like a scarlet bull’s pizzle. Did the painter intend this? Who can tell? He left no account of the picture. But he was a sly as well as a magnificent painter; also, a painter of magnificence, not afraid of controversy, indeed perhaps drawn towards it.

The pose is noble, heroic, but the hands make it subtler and more complicated. Not the hands of a concert pianist, as it turns out, but of a doctor, a surgeon, a gynaecologist.

And the scarlet pizzle? All in good time.

So yes, let’s begin with that visit to London in the summer of 1885.

The Prince was Edmond de Polignac.

The Count was Robert de Montesquiou-Fezensac.

The commoner with the Italian name was Dr Samuel Jean Pozzi.

Their first item of intellectual shopping was the Handel Festival at Crystal Palace, where they heard Israel in Egypt to celebrate the bicentenary of the composer’s birth. Polignac noted that, ‘The performance made a gigantic effect. The 4,000 executants royally fêted le grand Haendel [sic].’

The three shoppers also came bearing a letter of introduction from John Singer Sargent, the painter of Dr Pozzi at Home. It was addressed to Henry James, who had seen the picture at the Royal Academy in 1882, and whom Sargent was to paint in full mastery years later, in 1913, when James was seventy. The letter began:

Dear James, I remember that you once said that an occasional Frenchman was not an unpleasant diversion to you in London, and I have been so bold as to give a card of introduction to you to two friends of mine. One is Dr S. Pozzi, the man in the red gown (not always), a very brilliant creature, and the other is the unique extra-human Montesquiou.

Strangely, this is the only letter from Sargent to James which survives. The painter seems unaware that Polignac was also to be of the party, an addition which would surely have pleased and interested Henry James. Or perhaps not. Proust used to say that the Prince was like ‘a disused dungeon converted into a library’.

Pozzi was then thirty-eight, Montesquiou thirty, James forty-two and Polignac fifty-one.

James had been renting a cottage on Hampstead Heath for the previous two months and was about to return to Bournemouth, but put off his departure. He devoted two days, 2 and 3 July 1885, to entertaining these three Frenchmen who, the novelist subsequently wrote, had been ‘yearning to see London aestheticism’.

James’s biographer Leon Edel describes Pozzi as ‘a society doctor, a book-collector, and a generally cultivated conversationalist’. The conversation went unrecorded, the book collection is long dispersed, leaving only the society doctor. In that red gown (not always).

The Count and the Prince came from old aristocratic lines. The Count claimed descendence from D’Artagnan the Musketeer, and his grandfather had been an aide-de-camp to Napoleon. The Prince’s grandmother had been a close friend of Marie Antoinette; his father was Minister of State in Charles X’s government and the author of the July Ordinances, whose absolutism set off the 1830 Revolution. Under the new government, the Prince’s father was sentenced to ‘civil death’, so that legally he did not exist. Frenchly, however, the nonexistent man was permitted conjugal visits during his imprisonment, one of which resulted in Edmond. On his birth certificate, in the space for ‘Father’, the civilly dead aristocrat was listed as ‘The Prince called Marquis de Chalançon, currently travelling’.

The Pozzis were Italian Protestants from the Valtellina in northern Lombardy. In the religious wars of the early seventeenth century, a Pozzi was among many burnt to death for their faith in the Protestant temple of Teglio in 1620. Shortly afterwards, the family moved to Switzerland. Samuel Pozzi’s grandfather Dominique was the first to arrive in France, crossing the country in slow stages and finally setting up as a patissier in Agen; he Frenchified the family name to Pozzy. The last of his eleven children – inevitably called Benjamin – became a Protestant minister in Bergerac. The pastor’s family was pious and republican, devoted to God and conscious of its social and moral duties. Samuel’s mother, Inès Escot-Meslon, from the Périgord gentry, brought into the marriage the charming eighteenth-century manor house of La Graulet, a few kilometres outside Bergerac, which Pozzi was to cherish and expand all his life. Always frail, and worn out by child-bearing, she died when he was ten; the pastor swiftly remarried a ‘young and robust’ Englishwoman, Marie-Anne Kempe. Samuel grew up speaking both French and English. He also, in 1873, restored the family name to Pozzi.

The Man in the Red Coat Julian Barnes

Britain’s most passionate Francophile takes us on a wonderfully rich, witty tour of Belle Epoque Paris, via the life story of the pioneering surgeon Samuel Pozzi

Buy now