- Published: 17 August 2021

- ISBN: 9781784706654

- Imprint: Vintage

- Format: Paperback

- Pages: 320

- RRP: $26.99

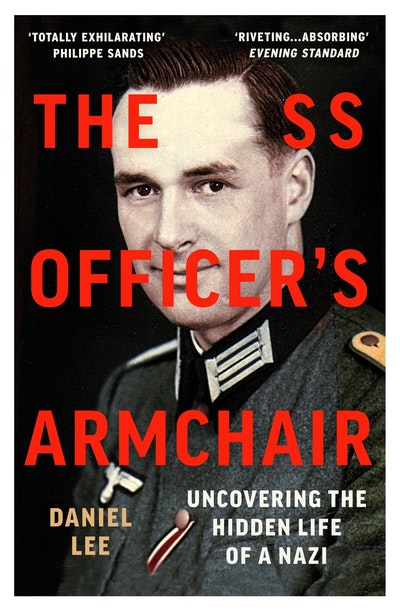

The SS Officer's Armchair

In Search of a Hidden Life

Extract

The five lawyers working at section IIIc of the Württemberg Police Department had little to look forward to, over the approaching dull and cloudy March weekend. As Friday drew to a close and the sound of typewriters and ringing telephones died down, Walter, Wilhelm, Kurt, Rudolf and Robert left their firstfloor office in the Hotel Silber, an imposing neo-Renaissance structure close to the tenth-century Old Castle in the centre of the historical Swabian city. But the weekend would prove to be far from quiet. Over the course of it, Hitler spectacularly – and illegally – remilitarised the Rhineland, marking a significant rupture with the terms of the Treaty of Versailles. As lawyers, the five men would have been concerned with future legal reprisals and the consequences of German reoccupation for multilateral diplomacy, so they would have had far more than usual to talk about when they returned to work on the Monday.

The five men formed a tight band, separate from the Hotel Silber’s 200 other employees.2 All in their late twenties or early thirties, three of them had studied law at the prestigious Tübingen University and, with the exception of Kurt Diebitsch, each had only joined section IIIc since the Nazis seized power a few years earlier. Outside the rigid confines of the Hotel Silber, the men and their families socialised together. The month before, they had celebrated the wedding of the tall, dark-haired and neatly dressed Robert Griesinger, the youngest and most junior of the five, who, after a drawn-out engagement, had finally married his sweetheart from Hamburg.

Since spring 1933 police section IIIc had played a distinctive role that allowed Nazism to take root and grow in Stuttgart. It was no ordinary police force. Rather, it was the headquarters of the Political Police for the state of Württemberg, known then and now by its more familiar name: the Gestapo. Under the Nazis, the Württemberg Political Police filled the Hotel Silber’s 120 rooms, spread out over six floors. The basement contained the Gestapo’s notorious torture cells. To this day, some of the elderly residents of Stuttgart continue to avoid Dorotheenstrasse because of the terrifying stories they heard as children about what took place in that basement. Walter Stahlecker was head of the Württemberg Political Police. A slender man with wire-rimmed glasses and shiny, thinning hair combed neatly back, he would go on to command Einsatzgruppe A, the mobile killing unit responsible for the murder of hundreds of thousands of Jews in the Baltic during the war. His stocky blond deputy, Wilhelm Harster, would serve in the Netherlands as head of the Security Police and the Sicherheitsdienst (SD) – the security and intelligence service of the Schutzstaffel (SS) – where he was instrumental in the deportation of more than 100,000 of the country’s Jews. As Stahlecker made his way across the Baltic, and Harster tracked down Jews in the Netherlands, Rudolf Bilfinger, who had been a junior secretary in the Stuttgart bureau, remained in Germany, where he worked at the Reich Main Security Office (RSHA) as head of the Organisation and Law Group. An associate of Adolf Eichmann, Bilfinger was, in 1942, one of the legal masterminds of the Final Solution.3 Later he was head of the Security Police and the SD in Toulouse.

Yet while the names of these three men can be found in studies of the Second World War, the same cannot be said of Kurt Diebitsch, the fourth lawyer, who was killed during the invasion of the USSR in 1941; or of the newly-wed Robert Griesinger, the fifth man, who finished the war working as a legal expert at a government ministry in occupied Prague.

Nazism had a devastating impact on the world and continues to fascinate, more than three-quarters of a century later. But most of us know the names of only a handful of Nazis who formed part of Hitler’s inner circle. What about men like Diebitsch and Griesinger, who have so far escaped the attention of films, documentaries and history books? These low-ranking Nazis are doubly invisible: overlooked by historians, but also forgotten or deliberately suppressed in the memories of living relatives. The onerous task of first identifying and, later, understanding the experiences and feelings of some of the regime’s nominal characters is important for what it communicates about consent and conformity under the swastika. Recovering lost voices from the past enables us to ask new questions about responsibility, blame and manipulation. They offer previously neglected insights into the rise of Nazism and the inner workings of Nazi rule.

This book tells two intertwined stories. One is the life of that young lawyer, Robert Griesinger. The other is the uncovering of that life, through a series of coincidences, research, cold calls, family lore, genuine or wilful forgetting and dead ends, and the ways in which the disturbing revelations reverberated in the lives of Griesinger’s descendants. The first interests me for the insight it brings into the mundane workings of Nazi Germany. I am implicated personally in the second, for my pursuit of Griesinger led me to (among other people) his two surviving daughters, Jutta and Barbara, born in 1937 and 1939 respectively, who shared their memories and, in turn, came to regard me as a source of information about the father who died during their childhood, and whose absence overshadowed the rest of their lives. For Griesinger’s daughters, the second generation of Nazi perpetrators, their father was then – and remains today – anything but nominal. Spending so much time with Jutta and Barbara blurred the traditional boundaries between historian and subject. They were eager for any details I could provide, to help them build up a picture of a father they barely knew or remembered. As a Jewish historian of the Second World War, whose family was deeply marked by the disasters and atrocities of that conflict, I felt the keen ambivalence of the role.

For me, establishing facts was an act of justice. I wanted to know more about Griesinger, this seemingly peripheral figure, in order to find out if he was guilty of anything. Jutta and Barbara became, in my mind, representatives of the father they had lost; they should, or so I thought, make amends for his actions by bearing witness, by acknowledging the weight of the evidence that I placed before them. Faced with questions about his involvement in Nazi rule, they remembered little and had been told less. Their most vivid stories had the dreamlike quality of childhood recollections: a miniature porcelain toilet that sat on Griesinger’s office desk; his light linen jacket soaked in blood as he carried the family’s injured dog to the vet; the green cloaks the sisters wore as they and their mother fled from Prague at the end of the war. Throughout my interviews with Jutta and Barbara, questions hovered in my mind like accusations: How could you not know? Why are you shielding him? Yet when I approached them as a total stranger, decades after their father’s death, they were kind, hospitable and willing to talk. As far as I could see them as people in their own right, I liked them. And one aspect of their experience strangely mirrored my own. For both our families, the traumas of the war were wrapped in an oppressive silence that became habitual over the course of generations. Secrets took on a palpable, looming presence, even if their existence was never acknowledged.4

We still know far too little about how low-ranking officials experienced the 1930s and 1940s, and Griesinger’s life helps us understand why Nazi rule was possible.5 The famous fanatics and murderers could not have existed without the countless enablers who kept the government running, filed the paperwork and lived side-by-side with potential victims of the regime in whom they instilled fear and the threat of violence. Griesinger also reveals the difficulty of trying to fit individuals into the categories usually applied to German people’s experience under Nazism.6 The young lawyer was neither a highranking Nazi nor one of the subordinates charged with overseeing the process of the Final Solution – those whose notoriety continues to ensure their remembrance. Nevertheless, his service at the Gestapo also excludes him from the category of ‘ordinary Germans’, which often lumps together everyone who, if not a political opponent, Jewish, Roma, disabled, black or homosexual, was therefore eligible to participate in the Thousand Year Reich. After all, to continue to go to work every day at the Hotel Silber as late as spring 1936 implies at the very least some support for the Nazi programme.

The narrative I trace will show how low-ranking officials might have existed in between two disconnected worlds; the first filled with the regime’s well-known high functionaries, and the second that comprised the ordinary German population.7 As many bureaucrats developed an intimate knowledge of the shape and scale of the new regime, even coming into contact with some of the Third Reich’s key protagonists, they also shared the same spaces and interacted daily with the bulk of the population at whom the new legislation was aimed. Griesinger was not an ordinary German: he was an ordinary Nazi. As agents of the state, he and tens of thousands of lower-ranking men and women like him – Gestapo agents, SS and Sturmabteiling (SA) auxiliaries, party members, together with civil servants, judges, teachers and government officials – had the power to shape the lives of their neighbours and the wider community.

Griesinger’s life allows us to understand what the rise of Nazism would have felt like at an individual level. Turning the gaze away from the German people as an indiscrete mass, and focusing instead on a single life, reveals how densely interconnected personal relationships and professional networks proved critical in allowing a new means of social organisation to take root and flourish in Württemberg, a German state previously renowned for its liberal parliamentary tradition and its aversion to political extremism.

*

Notes

Introduction

1 The national press covered the Winter Olympics on the front cover of every edition during the ten days of the competition. See the front covers of Der Angriff and Völkischer Beobachter, especially 7, 8 and 9 February 1936.

2 Hauptstaatsarchiv Stuttgart (hereafter HStAS), E151 / 01 / Bü 284, List of people and roles of those working in section IIIc of the Political Police, 1 March 1936. As a result of the destruction of documents at the end of the war, no definitive list survives that sheds light on the exact number of employees at the Political Police. I am grateful to Sigrid Brüggemann and Roland Maier for providing me with the figure of 200 and for so much information on the Hotel Silber, much of which appears in their publication: Ingrid Bauz, Sigrid Brüggemann and Roland Maier (eds), Die Geheime Staatspolizei in Württemberg und Hohenzollern (Stuttgart, 2012). Brüggemann and Maier’s figure of 200 appears in line with cities of a comparable size, such as Düsseldorf, where the Political Police employed 291 workers, forty-nine in administrative roles and 242 who carried out police work. See Robert Gellately, The Gestapo and German Society: Enforcing Racial Policy, 1933– 1945 (Oxford, 1990), 45.

3 Horst Junginger, The Scientification of the ‘Jewish Question’ in Nazi Germany (Leiden, 2017), 320.

4 For more on how people were affected in the longer term by their experience under Nazism, see Mary Fulbrook, Reckonings: Legacies of Nazi Persecution and the Quest for Justice (Oxford, 2018), 6.

5 Biographies of low-ranking officials who were not direct killers do not exist. Except for the rare occasion that a descendant, or someone with an intimate connection to an ‘ordinary German’, researches the Nazi past of a particular individual, their names, identities and trajectories are generally lost from history. Alex J. Kay points to a recent trend of biographical sketches of mid- and lower-level perpetrators and reveals that the average length of an entry is around a dozen pages. See Alex J. Kay, The Making of an SS Killer: The Life of Colonel Alfred Filbert, 1905–1990 (Cambridge, 2016), 128, n. 11. According to him, there exists only a small handful of individual biographical accounts of mid-level SS and police functionaries involved in genocide; Kay, The Making of an SS Killer, 1.

6 Two categories of Germans under Nazism generally emerge, when employing party or administrative rank, or participation in the Final Solution, as a benchmark from which to judge an individual’s significance to the period. Hitler, Himmler, Heydrich and all those at the very top of the regime make up the first. But this category also includes Stahlecker, Harster, Bilfinger and other less high-ranking characters, whose zeal towards policy implementation or Nazi ideology renders their actions worthy of scrutiny, and their names worthy of being remembered. Hitler’s millions of nameless and faceless followers make up the second category, placed together to construct a single grouping referred to commonly as ‘ordinary Germans’. It is a broad term that encompasses a variety of individuals, ranging from standard school teachers and factory workers who were not party members, to ‘real Nazis’ – Germans who took part in violent collective projects, such as concentration-camp staff or mobile killing units. For a discussion of ‘Real Nazis’, see Michael Mann, ‘Were Perpetrators of Genocide “Ordinary Men” or “Real Nazis?” Results From Fifteen Hundred Biographies’, Holocaust and Genocide Studies, vol. 14, 2000, 332–3.

7 This should not suggest that ‘ordinary Germans’ were somehow immune from contributing to mass murder. As Raul Hilberg, Christopher R. Browning and others have shown, most perpetrators and killers were ‘ordinary Germans’ who were drawn from a wide spectrum of German society. See Raul Hilberg, The Destruction of the European Jews (3rd edn, New Haven, CT, 2003), 1084; Christopher R. Browning, Ordinary Men: Reserve Police Battalion 101 and the Final Solution in Poland (London, 2001), 192.

The SS Officer's Armchair Daniel Lee

A historical detective story and a gripping account of one historian’s hunt for answers as he delves into the surprising life of an ordinary Nazi officer.

Buy now