- Published: 16 February 2021

- ISBN: 9781529106107

- Imprint: Ebury Press

- Format: Trade Paperback

- Pages: 288

- RRP: $35.00

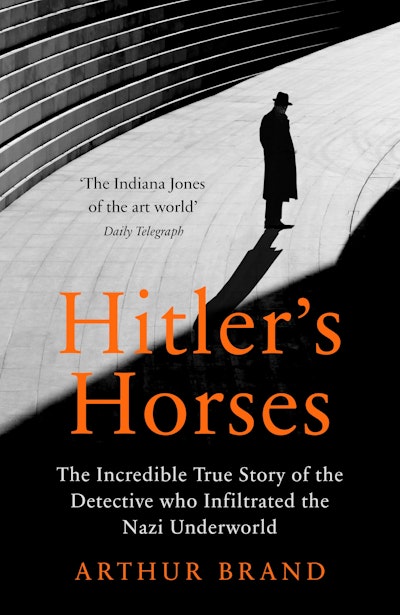

Hitler's Horses

The Incredible True Story of the Detective who Infiltrated the Nazi Underworld

Extract

The bunker is virtually cut off from the outside world and there’s an apocalyptic feel to the place. Only one tele - phone line is still working. Large quantities of alcohol are being downed to wash away the thought of what is to come. Only Hitler still believes in final victory. As he moves non-existent divisions around a map, one of his generals enters.

‘Mein Führer, our counter-attack to the north of Berlin has failed. Eberswalde has been taken by the Russians.’

In fact, Eberswalde, a small town about 50 kilometres north-east of Berlin, would only be captured four days later by the Russians, on 26 April. But for Hitler, this report – the result of a miscommunication – is the final straw. Overcome by one of his fabled attacks of rage, he rails against his generals.

‘They have betrayed me! It is over. The war has been lost. The only course left to me is suicide.’

Seventy years later, Eberswalde will make international headlines again in connection with one of the longest-kept secrets of the Second World War and the Cold War . . .

1

Livorno, Italy

2014

As soon as the plane brakes on the runway and my fellow passengers heave a sigh of relief, I always start to stress out. Where are the taxis? Will the driver go round the town three times and charge me an astronomic fee before dropping me off? Sometimes I’m lucky enough to get picked up. Depending on who my contact is, a car with diplomatic number plates might await me, or a chauffeur-driven limousine, sent by a wealthy client.

At Pisa Airport I was met by a man from a Chinese takeaway. Who turned out not to speak English. Gesturing towards the back of his white van, he wrenched open the rear door with some difficulty and shoved me inside. The floor was covered in empty soft-drink bottles, crumpled menus, a torn sack of rice and a mouldy green pepper. The stench was appalling. Legs braced, I crouched against the side. The passenger seat was occupied by a bag of food containers. Clearly I was just a consignment squeezed in between two deliveries. The driver shot off as if his life depended on it, not bothering to avoid the potholes.

I felt relieved. Admittedly, my flight had been massively delayed, but I’d got through Customs in one piece. Not that I had anything to hide, but the man I was on my way to see possessed a strange sense of humour. It wouldn’t have been the first time that a Customs officer had picked me out of the queue. ‘We’ve had an anonymous tip-off that you’re smuggling art.’ I’d be led off, to curious and disapproving looks from my fellow passengers. On arrival at my destination, my host would grin broadly. ‘So, how was your trip?’ Luckily he hadn’t played any pranks on me today.

For weeks I’d managed to put off this meeting. After I’d run out of excuses and the threats were ramping up – ‘If you don’t come now, I’ll have you fetched’ – I bought a ticket. A day return from Amsterdam.

After a short drive, the van stopped abruptly. The driver jumped out, opened the rear door and pulled me out by my arm. He bowed slightly and drove off. I took a deep breath. The reek of the van had made me nauseous.

I was standing in front of a grey five-storey building. The sunlight blinded me, but I recognised the surroundings: the canal with clear blue water in which you could see fish swimming, the little stone bridges and the clusters of parked scooters. On the other side of the canal stood Livorno’s impressive fort, built back in the day by the illustrious Medici family. I walked to the door and rang Professor Richardson’s doorbell. My host changed his identity regularly, and here he was passing himself off as an English professor.

‘Chi è?’ someone asked through the intercom.

‘Arthur.’

I climbed the stairs to the fifth floor. The last time I’d been here, there’d been a power cut and I’d been stuck in the lift for an hour. The front door was open. A small Filipino man in a starched white shirt and a black waistcoat stood in the doorway, smiling at me.

‘Mr Brand, always good to see you.’

I had a soft spot for Noah. He was working illegally in Italy to provide his wife and two little daughters in the Philippines with a better future.

‘Sir is in the living room, working.’

I handed him my coat and entered the living room. Sir turned out not to be working at all. Sprawled across his desk, he lay with his head on the keyboard, snoring away. Soft strains of Italian music came from the computer. Sleeping like a baby, that’s how I preferred to see him. Because once he was awake, you had to be careful of this colourful character. He was one of the most dangerous guys the art world had ever known: Michel van Rijn.

I’d made his acquaintance 15 years earlier. At the time I was taking my first steps in the art world, as a collector. One of my acquisitions, a painting by the French postImpressionist artist Paul Madeline, for which I’d paid several thousand guilders, turned out, after technical analysis, to have been painted around 1950. A minor miracle, given that Paul Madeline had been dead for 30 years by then. Just like any art collector starting out, I’d been ideal prey for forgers and other fraudsters.

Shortly after this I came across an old newspaper article about a man called Michel van Rijn. It quoted a Scotland Yard spokesman as saying, ‘This Dutch villain’s mixed up in ninety per cent of all the big art world scandals, and likes to claim he’s involved in the remaining ten per cent.’ My interest was piqued and I looked for more information online. It turned out that, these days, van Rijn was a reformed character. Since the mid-1990s he’d been working together with Scotland Yard and other police forces to solve crimes related to the art world. He also had his own website on which he unmasked dodgy art dealers, forgers and thieves, something that these unsavoury characters – his former ‘colleagues’ – didn’t view too kindly. But there were also rumours that van Rijn had never really retired from his old ‘profession’. It was thought that he was still active, and merely using his police contacts as a cover. The whole story fascinated me, and I decided to approach van Rijn. Who better placed than he to warn me about the pitfalls of the art trade? I took a chance and sent him an email. To my surprise, he invited me over to his penthouse in Park Lane, one of the most expensive streets in London.

That first meeting, 15 years ago, was something I would never forget. He asked me to sit down at a table, next to a plastic skeleton – ‘My eighth wife, and the best one yet, because she never contradicts me’ – before going back to work on his computer. For an hour he hardly said a word. Until the doorbell went. ‘That must be the postman. Could you open the door?’

I collected the parcel and came back into the room.

‘I need to make an important call,’ van Rijn said. ‘Wait in the corridor a sec, and while you’re at it, open that parcel.’

After about five minutes I assumed it was all right to re-enter the room, holding the book I’d unwrapped. Van Rijn sat there grinning at me, his fingers in his ears. ‘Phew, it’s only a book. I’ve got so many enemies that every parcel could contain a bomb.’

By the end of the day van Rijn had concluded that I was the biggest goofball he’d ever met – far too naive for the devious and sometimes dangerous world of art dealing. As we said goodbye, I assumed it was for ever, but he said, ‘Come back soon, I like hanging out with weirdos.’ In the years that followed I visited him regularly. He introduced me to his police contacts, as high up as Scotland Yard, but also to the biggest fraudsters in the art world. I couldn’t have wished for a better education. I was able to witness at close quarters various operations of his that made international headlines.

In recent years van Rijn and I had grown apart. He moved house so often that we saw each other less and less, and we’d also had a few run-ins. But a few weeks earlier he’d suddenly rung me. ‘I’m on to something amazing. Really mind-blowing. Take it from me, it’ll never get any bigger than this.’ He’d refused to say any more, insisting that I come to Livorno to see him in person. I’d hesitated for a long time. A day with van Rijn was more exhausting than running a half-marathon, and what’s more, this meeting could be a trick. Maybe he was trying to get me to do the dirty work in some dodgy deal. But in the end I’d given in and made the journey to Livorno.

Van Rijn was still snoring away with his head on the keyboard. The desk of one of the world’s greatest art experts was covered in knick-knacks and novelty objects. I picked up his favourite toy, held it next to his ear and pressed the button. The grilled chicken started to sing: ‘Feeling hot . . .’

He went on snoring.

‘Wake up!’

Even that didn’t help. Clearly stronger measures were called for. I cupped my hands to his ear and yelled: ‘Police!’

Van Rijn woke with a start, rubbed his bloodshot eyes and looked at me in surprise. ‘Good grief! What are you doing here?’

‘You asked me to come,’ I answered.

He thought for a moment. ‘But you weren’t coming till Monday, right?’

‘It is Monday.’ He heaved himself out of the chair and gave me a bear hug. With his broad face, rough beard and wild grey locks, he looked like an old sea dog.

‘Did you come by taxi?’

On the whole, van Rijn had the memory of an elephant. So it was disconcerting when he forgot the simplest things.

‘No, you sent some Chinese man.’

‘Oh yes – great guy. And an excellent chef. He’ll be bringing us a rijsttafel in a minute.’

My stomach started to heave at the memory of the van and its smell. Van Rijn lit a cigarette and walked into the kitchen. I looked around the living room. Hunched in an old smoking chair, next to a punchbag that hung from the ceiling, was his eighth wife, the plastic skeleton. A cactus several metres high stood in the centre of the room, surrounded by an antique gumball machine, a statue of Superman and a giant porcelain pig.

Van Rijn came back with two mugs of coffee and put them on the lounge table, a sheet of plate glass resting on a bright pink reclining mermaid.

‘Thank you,’ I said, ‘but I don’t drink coffee. I thought you knew that by now.’

‘I do. These two are for me. If you’re thirsty, help yourself to something else.’ He threw himself down on the sofa. ‘I’ve made an earth-shattering discovery. America wasn’t discovered by Columbus. Just take a look at the cover of this auction catalogue.’

The catalogue came from a famous international auction house. Its cover featured a beautiful Roman mosaic depicting five birds around a drinking fountain.

‘Lovely,’ I said. ‘But what does Columbus have to do with it?’

‘Do you know what those birds are?’

As a city boy, ornithology wasn’t my strong suit. I could just about tell a duck from a pigeon.

‘Uh, that one on the left is a parrot.’

‘Correct. So . . . ?’

‘I don’t see what you’re getting at. The Romans kept parrots as pets, right?’

‘Sure, but this little chappie happens to be a blue-andyellow macaw, only found in the rainforests of South America . . .’

I burst out laughing. A South American parrot on a Roman mosaic, 1,500 years before Columbus reached America.

‘How embarrassing for the auction house,’ I said. ‘Where did the forgery originate?’

‘Tunisia, I think. There’s a village just south of Sousse where they churn out fake Greek and Roman mosaics. A regular goldmine.’

Van Rijn smiled. He knew how much I enjoyed that kind of sleuthing.

‘What are you going to do about it?’ I asked.

He shrugged. ‘I still haven’t made up my mind. I could tell the press, obviously, and make the auction house look ridiculous. But perhaps I’ll just buy the mosaic.’

‘Buy it?’ I stared at him in surprise.

‘Yes. Then I’ll “discover” that it’s fake and demand my money back. Plus compensation for emotional damage of course, since it was a present for my wife on our twenty-fifth wedding anniversary or something like that.’

‘You haven’t dragged me all the way here just for a parrot, I hope.’

He bent forward conspiratorially, his eyes shining. ‘No. I’m on to the biggest thing ever.’

Van Rijn always had a hidden agenda. I’d learnt to be on my guard.

‘Michel, I’m sure it’s something great, but why am I here?’

‘I thought you’d be glad to see me.’

‘Of course I’m glad to see you. I’m always glad to see you.’

He tilted his head to one side, narrowed his bright blue eyes and stared at me, as he did when he felt I was lying. I suspected him of being able to read thoughts. He was usually a few steps ahead of me. That, combined with his manipulative tendencies, was what made him so dangerous. A Scotland Yard detective had once confided to me that they were always wary of van Rijn, even though they were working with him.

‘I’m not as young as I used to be,’ he sighed. ‘This affair is highly complex and mysterious. And it’s not without risk.’

In the past, he’d never shunned risk. In Central America he’d hacked his way through the jungle with a machete in search of lost Mayan cities. In Northern Cyprus he’d banded together with Turkish generals to pillage monasteries and churches. Over the years, he’d made a lot of enemies. In Rome the Mafia had tried to assassinate him, and in Amsterdam Yugoslavian criminals had shot at the car he was in, riddling it with bullets. Online and in the media it was speculated that he had a guardian angel. There was a rumour that he was being protected by Mossad, the Israeli secret service. He told me this wasn’t true, though one of his best friends, Hesi Carmel, was a famous Mossad agent.

‘Michel, stop beating about the bush for once. My flight here was delayed and we don’t have a lot of time.’

He got up and walked to the window. ‘Arthur, I want to take on this job, but I can’t. In a minute you’ll understand why.’ He turned round and looked at me. ‘I need your help.’

Whenever he asked for my help, it was usually because there was something in it for him. But this time he sounded sincere, almost vulnerable.

‘Okay.’

He smiled. ‘I knew I could count on you. And I’m confident you might just pull this off. You look like a choirboy and you come across as incredibly naive, so they’ll underestimate you.’

He could compliment you and insult you in the same breath.

‘What’s the biggest mystery you’d like to see solved?’ he asked.

I didn’t have to think very long. ‘El Dorado.’

The myth of a gigantic treasure that Spanish conquistadors and other adventurers had searched for in South America had fascinated me since boyhood.

He shook his head. ‘I mean something that really existed, you idiot.’

He should have known better. Around ten years earlier, he’d made international headlines with the discovery of the Gospel of Judas. No one had any idea that this long-lost manuscript still existed. It was The Da Vinci Code, but for real. The Catholic Church had kept this gospel out of the Bible by destroying all existing copies. But one copy survived, because 1,700 years ago a monk had hidden it in a cave in Egypt. In the Gospel of Judas, Judas isn’t a traitor, as the Bible teaches us, but the only true disciple of Jesus. The Vatican even issued a press statement distancing itself from the rediscovered gospel.

‘Let me give you a clue. It’s to do with the Second World War.’

Now I knew what van Rijn was driving at. During the Second World War, the Nazis had not only carried out the biggest mass murder in history, but also the biggest art theft of all time. Countless artworks were confiscated on the orders of Adolf Hitler and his second-incommand, Reichsmarschall Hermann Göring. The Nazis sold part of their loot to fuel the war machine; the rest disappeared into the private collections of Hitler and Göring. Hundreds of thousands of items have never been recovered, including paintings by Rembrandt and Van Gogh. In 2012, German police found over 1,000 long-lost objects in an apartment in Munich. There was one missing art treasure in particular, though, that continued to fascinate people. Seventy years after the war, fanatical treasure seekers were still scouring lakes and caves for the ‘Eighth Wonder of the World’.

‘The Amber Room,’ I answered.

The Amber Room was a room in the Catherine Palace, just outside St Petersburg – the summer residence of the Russian tsars – decorated with magnificent panels made of amber, fossilised tree resin. Eyewitnesses said that when sunlight lit up the amber, its splendour was unforgettable. In 1941 Hitler ordered his troops to dismantle the room and transport it to Germany. The amber panels were stored in a castle in Königsberg, where they went up in flames during heavy bombing by the Allies in 1945. In 2003, President Putin and the German Chancellor Gerhard Schröder opened a reconstruction of the room in the Catherine Palace. But not everybody was convinced that the original Amber Room had really been destroyed. During the Third Reich’s desperate endgame, special SS commandos were sent off on top-secret missions to hide art treasures in lakes, woods and caves, and some thought the Amber Room had been a part of one of these evacuations. According to some sources, these commandos were later murdered by their officers to ensure there were no witnesses left.

Hitler's Horses Arthur Brand

How the Indiana Jones of the art world took on neo-Nazis and the criminal underworld to solve the mystery of Hitler's favourite statue.

Buy now