- Published: 25 November 2021

- ISBN: 9781529192483

- Imprint: Ebury Digital

- Format: EBook

- Pages: 304

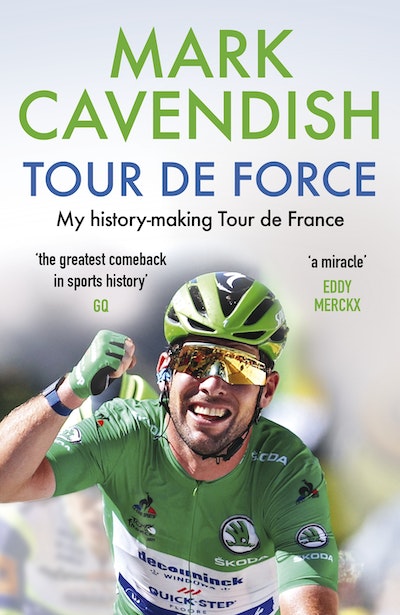

Tour de Force

My history-making Tour de France

Extract

I got up, dusted off the grit and looked through the front windscreen. My girlfriend, Sarah, was watching me while messaging friends, updating them through the multitude of social platforms she uses.

Sarah’s court matter for allegedly disclosing confidential information had been mentioned in the Downing Centre Local Court earlier that day. Reporters knocking on the door at her old house the previous day had failed to find her. But then a gaggle of reporters and photographers had descended on her mother’s house, where we were staying. It seemed getting a photograph of Sarah was a matter of national importance. I knew we’d be relatively easy to find so I’d warned the neighbours, who texted saying there were a handful of snappers outside with large cameras; one of the cameras was set up on a tripod on the footpath.

I hoped I could get the media reps to go away by calling their bosses, many of whom I knew very well. One of the reporters had identified herself as being from The Australian, so I called a long-time contact at the paper, senior journalist Paul Maley, and registered my displeasure, refusing an interview. Paul came back to me a short time later saying the crew would stay until they had a shot of Sarah. We were offered the opportunity to ‘stage’ a candid shot – ‘We’re going to get you eventually,’ I was told – but Sarah wanted to maintain her privacy.

I had locked the entrance gate earlier that afternoon in anticipation of reporters. The media weren’t certain we were home, and I avoided confirming this when I spoke to Paul. As we had the upper hand, I started planning our covert exit. Sarah booked an Airbnb for three nights in Zetland in inner-city Sydney and we closed the house blinds, locked the doors and left the lights off to confuse the reporters.

We stayed inside to avoid a long-range snap or the possibility of overhead footage taken by a drone. A neighbour sent me a photograph of the reporters, taken from her upstairs window. We waited. After darkness fell, one of the reporters climbed the front gate and walked down the side of the house. Sarah wanted to call the police, but that would have confirmed we were home.

Soon after, another neighbour rang to tell us there were now only three journalists, all wearing jeans and hoodies, all with long-lens cameras. I thought we would give it until 8 p.m. My years in surveillance had taught me that there comes a point when you don’t expect to see whoever you are watching and waiting for until the next day.

Just before 8 p.m. the same neighbour texted to say that the silver-grey Mazda CX-9 that had been parked across the road all afternoon had left with all three occupants on board. I smelled a trap: I figured they had moved their car to the nearby shopping centre and had moved back on foot under the cover of darkness into a park across the road.

I waited another hour, then threw our bags in the car and drove off for ten minutes or so to make sure I had no tail before returning to pick up Sarah, who was waiting in a hoodie and sunglasses. I slipped into a familiar anti-surveillance mode, becoming suspicious when there was no tail and worried that a tracking device might have been planted on the car.

That’s why, on 18 September 2018, I was searching the car’s underside. I had semi-hoped that I would find a device so that I could attach it to another car to divert the media for a couple of days, but our car was clean. We drove around until I was absolutely sure we weren’t being followed and then turned into the Airbnb. It had the feel of a safe house.

We ordered from Uber Eats and bought a bottle of gin, some tonic water and a lemon from the bottle shop across the road. After toasting our escape we set up a decoy – a loyal friend of Sarah’s – to visit the house the next day to collect any mail and pose momentarily. With a bit of luck they would believe it was Sarah, and with a bit more luck they might even run the pic in the papers.

After thirty-two years in law enforcement, I was on the run from reporters.

PART I

1

SIN CITY

MY FIRST DAY as a rookie cop, Monday 9 June 1986, was a typical early winter’s day in Brisbane, Queensland: warm, with the smell of fermenting Moreton Bay figs. I pulled into the dirt car park adjacent to the Fortitude Valley Police Station, locked the doors of my grey Ford sedan and checked my wristwatch. It was 3.30 p.m., half an hour before my 4 p.m.–12 a.m. shift.

I had graduated from Oxley’s Queensland Police Academy the previous Friday in J Squad of the 1985 intake, and had spent a sleepless weekend eagerly anticipating getting ‘out on the road’ to preserve Her Majesty’s peace and protect life, liberty and property, as I had solemnly sworn. I had laid out my street uniform the moment I got home from the graduation ceremony and gone over my checklist at least twenty times that weekend, making sure I had all the creases properly ironed into my shirt and trousers, my boots were spit-polished, and all of my accoutrements were functional. When I wasn’t obsessively checking my uniform, I was refreshing my memory of policing protocols by reading the two large tomes that comprised the Commissioner’s Instructions.

Adrenaline caused me to open the heavy front door of the police station too vigorously, and it swung ponderously, unchecked by either a hydraulic door-closer or a doorstop, and thudded loudly into the wall of the front vestibule where the public counter stood. The constable seated behind the counter started a little but then looked at me quizzically once he recognised that the intruder was wearing a uniform and was not a threat. He looked as young as I was: twenty-one. I shrugged apologetically while trying to move off from my embarrassing entrance, and declared somewhat officiously that I was reporting for duty.

Behind the constable I could see through to the station sergeant’s office. Sitting up on a dais in a high-backed, throne-like swivel chair, I saw a toad-like figure wearing the uniform of a senior sergeant. In one hand he held a folded copy of The Courier-Mail and a cheap biro with a well-chewed end; with his other hand he pulled his reading glasses disapprovingly down his nose. I realised my ostentatious arrival had interrupted his deciphering of a crossword clue.

The counter constable pointed to the door and I walked through apprehensively, trying to make my tall, lanky frame appear as obsequious as possible. I introduced myself to the Toad, who was now frowning at his crossword and pretending I wasn’t in the room. I waited an interminable sixty seconds while he scratched with his pen, and then I repeated my introduction, louder this time in case he had a hearing difficulty. He looked at me over his glasses again and then looked theatrically at a black Casio watch that was doing its best to recede into his fleshy wrist. He said, ‘It’s three thirty-four. You don’t start until four o’clock. Sit down over there and wait until you actually start duty.’

Suitably admonished, I sat down on a bench seat and waited. In the thirty-two years since then I’ve learned patience, but I wasn’t born with it and I certainly didn’t have it then. This man was standing between me and my career and I was trying desperately to figure out why. Was he simply teaching me a disciplinary lesson? Did he not like my name or my dark features? I’d had plenty of that at school, but didn’t expect it from a senior cop. Maybe he was just old, tired and burnt out.

The police radio in his office was tuned into the district frequency, and I tried to suppress my excitement each time I heard the crackling of the speaker heralding a police call. Mobile cars were being deployed to routine jobs such as a drunk in a pub, a disturbance at a house, a shoplifter at Myer and a suspicious car at New Farm Park, and I was impatient to join the fray. My impatience was obviously clear to the Toad, who occasionally attempted to quell my fidgeting and the creaking of my unsoftened leather belt with a stern sideways look.

Several other new graduates arrived and were unceremoniously ushered to the bench seat while an ebbing and flowing of police marked a shift change at the station. I saw that the cops normally arrived and left through a back door; this provided a more discreet thoroughfare and more direct access to the locker room, which appeared to be the central hub.

Finally, at 4.05 p.m., the Toad picked up a clipboard, spun his chair towards the reserves bench and, like a football coach, spat out our positions for the afternoon shift. He unapologetically mangled my name in a gravelly voice: ‘Kwaydflig, beat duty. Come and see me for instructions.’ The Toad was a man of few words.

The other graduates had been assigned to mobile cars, and after signing out their Ruger .357 Magnum police revolvers they ventured eagerly into the locker room in search of their allocated senior partners. As I loaded cartridges into my revolver, I noticed the Toad watching me. His wobbling jowls were the only discernible sign that he was shaking his head. I said, ‘Okay, Sarge, I’m ready. What do you want me to do?’

He leaned back in his chair, the reclining mechanism protesting in squeaks, and linked his fingers as his hands rested on his ample paunch. He said, ‘You’re to walk from here to the intersection of Brunswick and Wickham streets, where you will remain static and observe. You are not to move from that location unless I tell you to. You are not to talk to anyone unless they talk to you first. You will call me every hour, on the hour, on that radio. I don’t want a conversation: I just want to know if you’re still alive. So one call per hour, using your call sign, will suffice. You are not to arrest anyone without getting my express permission first. At 11 p.m. you will start walking back to the station and let me know that you’re on your way back. Unless you’ve got something very important to tell me when you get back, I don’t want to see you – so you can just go home. Understand all that?’

I nodded enthusiastically and responded before he’d finished speaking, ‘Yes, Sarge.’

He rolled his eyes and said, ‘It’s “Senior”. Now get out of my sight.’

I walked hastily towards the front door, checking that my accoutrements were in the right place on my belt. I don’t know why we were forced to call our equipment ‘accoutrements’. I liked the sound of the word, but listening to the old-timers saying it with a broad Australian twang was odd. I pressed the ‘TALK’ button on my radio to hear piercing but reassuring feedback come through on the station sergeant’s speaker. The Toad bellowed at me from a distance as I opened the front door to exit: ‘And young fella, I know your type. You’re going to ignore my instructions and get yourself into a blue. I’m telling you now, if you’re going to pinch anyone after 10 p.m. you might as well take them home, because I’m not giving you a car to take them to the watch house, and you’ve got Buckley’s of me approving overtime for the paperwork.’

I could only say, ‘Yes, Senior’, and boldly move towards the Valley centre at a slightly faster clip than the ‘two and a half miles an hour [4 km/h] by the left’ that the Commissioner’s Instructions dictated as the desired patrolling pace for beat constables. I had always guessed this just meant a slow walk and keeping to the left of the footpath. My bold stride, which struggled to stay below the designated speed limit, betrayed my overconfidence. I had graduated dux of my police squad and had broken a longstanding record by scoring 97.5 per cent in my final exam – the previous highest score on any Academy test had been 96 per cent. I had excelled at the practical components as well. So the moment I walked out of the Fortitude Valley station door I was certain I was taking my first steps to becoming the future Commissioner of Police.

However, as each long stride took me closer to my assigned post for the evening I lost some of that brashness, and by the time I took up my position at the designated intersection I was wondering whether I could remember how to take a trivial complaint by myself, let alone make an arrest.

My mettle was soon restored when I noticed a man watching me from a Wickham Street entrance to some flats positioned above shopfronts, diagonally opposite from where I was standing. I pretended not to notice but occasionally studied his movements as I watched over pedestrian and car movements at the crossroads. Eventually he broke cover, sauntered across the roadway, and made his way west along Brunswick Street as I watched out of the corner of my eye. When he thought he was out of sight he crossed over to my side and approached me from behind as I stood looking towards New Farm. Watching him reflected in the shop windows on the opposite side, I inconspicuously drew my short baton, and as he stepped closer I spun around and raised the baton. He leapt back and stood frozen looking at me. I saw a pasty, skinny youth of about seventeen, his clothes ill-fitting and his face covered in fresh acne and old scarring. His eyes had dark raccoon rings, his mouth had sores and his longish hair was greasy.

He broke the silence and said, ‘I just want to ask you the time’ as he shook his left arm to make his sleeve slide surreptitiously over his wristwatch. I pointed my baton at his arm and replied, ‘Isn’t your own watch working?’ He looked down sheepishly at his arm and snarled surlily, ‘Nah, the battery’s dead.’ I retorted, ‘You’re the one that’s going to end up dead if you keep sneaking up on cops like that. What’s your name?’

So began my very first interaction as a cop. I tried to get his name and address from his evasive responses and pocket litter – I thought about calling through on the radio for a name check, but the Toad’s warning about not talking to people was still ringing in my ears and I didn’t want to risk getting called off the road after only an hour of duty. In my best police officer’s tone I told him to move on and said I’d be keeping an eye on him. I was still watching him when a marked police car pulled up next to me and the single occupant beckoned me over to the window.

A florid and rotund uniformed man wearing a name badge that declared the arrival of Senior Sergeant Mick Silvester leaned over from the driver’s seat and said, ‘What’d that shitbag want?’ I replied, ‘He said he wanted to know the time, but I think he was trying to see how close he could get to me without me seeing him.’

Silvester told me: ‘He’s one of the local grubs. He’s just testing you out. Tell him to fuck off next time or just take him down a laneway and give him a touch-up. I’m Tweety.’ With that introduction he extended a shovel-sized hand, which I shook before he drove off with a cheery ‘See you when you’re rostered with me’.

I realised I hadn’t introduced myself as I watched ‘Tweety’ Silvester accelerate into a hard right turn onto Warner Street with puffs of smoke coming from his spinning rear wheels. I thought of Tweety Bird. I thought of Sylvester the Cat. I also thought police weren’t the best comedians. But the name oddly suited him.

I didn’t make an arrest that night, contrary to the Toad’s prediction, but it wasn’t for want of trying. It’s just hard to find anyone to arrest when you’re standing like a sentinel in full uniform under bright streetlights as a visible deterrent, which was of course exactly the Toad’s intent.

Tour de Force Roman Quaedvlieg, Mark Cavendish

Just how did Mark Cavendish, the greatest sprint cyclist of all time, return from being seemingly dead and buried at 36 to become the Tour de France's most successful ever stage winner?

Buy now