- Published: 1 March 2022

- ISBN: 9780143788096

- Imprint: Viking

- Format: Hardback

- Pages: 704

- RRP: $49.99

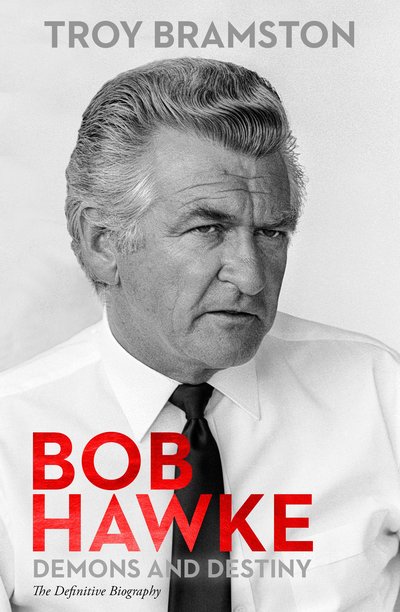

Bob Hawke

Demons and Destiny

Extract

The image of Hawke in these final days is lodged in my memory. He wore beige golf pants with a shiny tracksuit top over a white polo shirt, and slip-on shoes. His eyes were a duller blue than usual, though still piercing. His hair, once a luxuriant mane, was thinning, whiter and losing its distinctive curl. He was tired and a little irritable. He had lived a long life: he was less than a year shy of his ninetieth birthday. He was fading. It was deeply affecting to see Hawke ready, even eager, to let go. This son of the manse did not know what afterlife there might be. He had long been agnostic, but never an atheist. But he had thought about death, and was coming to terms with it. When I asked how he was feeling, his reply was blunt. ‘To be quite honest, mate, I’d be quite happy not to wake up tomorrow morning,’ he said. Three months later, Hawke was dead.

Hawke would rather tackle a cryptic crossword or complete a sudoku than answer yet another round of questions for this biography. This was what occupied his days now. There had been a passing parade of former colleagues, rivals, friends and family members in recent weeks, and this would continue until the end finally came. He usually welcomed it, sometimes tolerated it and often enjoyed it, even if it did distract from the brainteasers.

It would be the last time I saw Hawke, and it soon became clear this interview was different. Although increasingly brief in his responses, Hawke was more reflective than usual. He had been thinking about his life. He was concise but thoughtful when recalling his student days, his time in the union movement and his prime ministership. When asked about his parents, Clem and Ellie, or his wives, Hazel and Blanche, or his children, he got emotional. His eyes moistened when he talked about Paul Keating.

There was a jolt of energy when I asked Hawke, again, about his parents. He lifted up in his chair and his eyes sparkled when he spoke about Clem. ‘He was a marvellous man, my father, he always looked for good in people and he was a very big influence on me,’ Hawke said. ‘He was very keen to see that I made the most of what I had. I liked him. I loved him. He was my best mate.’ Clem and Ellie Hawke showered their second son with love and fostered in him the belief that his life was destined for a great purpose. Did Ellie crystalise her ambition for her son and believe he would become prime minister? ‘I think so,’ he replied. ‘At least in the back of her mind. Yes, I think it was there.’ And Clem? ‘Dad was at least as ambitious for me as my mother was.’

Hawke had spoken about how deeply he loved Hazel. He regretted not being a better father to Susan, Stephen and Rosslyn. Or a better husband. He thought he was a better grandfather. He acknowledged his adultery and the impact of the ‘demon drink’ on their marriage. In this last interview, he described his relationship with Hazel as ‘the most important in my life at that time’. When clarification was sought, he became a little tetchy and made it clear he was indeed talking about Hazel. He had always loved her, even if he had not been faithful. He also loved Blanche. He said she was ‘the best thing that happened to me’. He had spoken, somewhat awkwardly, about their intellectual, emotional and physical love for each other. She was the light in his life. Her care for him in these later years, as he was slipping away, had deepened their love for one another. Hawke had spent a lifetime trying to convince people that he was a simple, ‘dinky-di’ Australian, but in truth he was complex. Most people are. He did not see any difficulty loving both Hazel and Blanche. They were the two great love stories of his life.

In recent years, Hawke had repaired any lingering rift with Keating. The mending of this relationship had been a work in progress for a decade; it was not a near-death reconciliation. (I was sitting with Keating in mid-2016, for example, when Hawke rang to talk about a rather routine matter, and they chatted amiably for several minutes.) They were Australia’s greatest political duo. They were rivals, and sometimes felt contempt for each other, but there was also admiration and warmth between them. They were like brothers. They never hated one another. Hawke’s eyes widened and he smiled when he told me how happy he was that he had seen Keating recently. ‘We had a marvellous time,’ Hawke said. ‘We did a lot of great things together.’ He had earlier told me: ‘Affection is not an inappropriate word, now, for our relationship.’

After a series of interviews for this book, and many more over the past decade and a half, this was an opportunity to clarify a few things, to plug a few gaps and ask any questions that might help illuminate the life of one of the most remarkable and consequential Australians. Hawke had been interviewed thousands of times since the 1950s – probably more than any other Australian political figure – yet trying to unravel who he really was, what motivated him, how he saw himself, the effect he had on others and the contribution he made to public life still needed exploring. He had been asked the same things over and over again, so my goal was to prompt more revealing responses.

As he neared the end, Hawke was not interested in pushing a legacy or dwelling on regrets. ‘I know this probably sounds a bit boastful, but I think I handled the prime ministership very well,’ he judged. ‘I’m not saying I was perfect – there were some things perhaps I could have handled better – but overall there is nothing I would change.’ In his final months, Hawke thought about what he had achieved and not achieved. He thought about those whom he loved and who had loved him. He was at peace with himself and others, and with his legacy. He died a few months later.

Bob Hawke Troy Bramston

The definitive full-life biography of Australia’s 23rd prime minister; the only one that Hawke cooperated with after exiting the prime ministership.

Buy now