- Published: 31 October 2016

- ISBN: 9780143782094

- Imprint: Ebury Australia

- Format: Trade Paperback

- Pages: 304

- RRP: $34.99

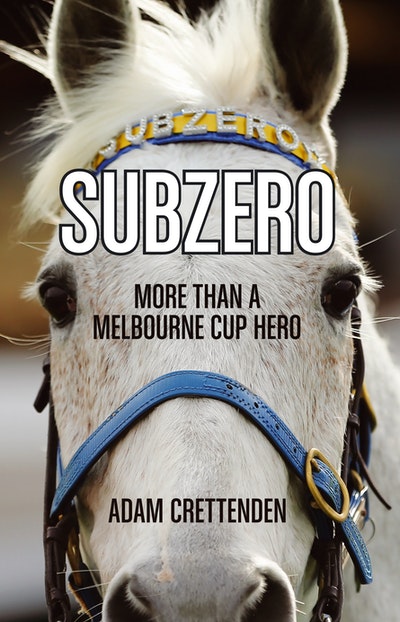

Subzero

More than a Melbourne Cup Hero

Extract

The morning of Monday 26 September 1988 was cool and crisp in Scone, a country town about a three-hour drive north of Sydney. It was early spring and the breeding season was in full swing. At Wakefield Stud, a 700-acre parcel of land less than five minutes’ drive from the centre of town, there was plenty of activity. Staff numbers swelled to capacity at that time of the year.

In the misty air, not long after sunrise, newcomer John Doherty was finishing the morning feed round to the resident stallions. At just 23 years of age, Doherty was on his first excursion outside of Tipperary in Ireland, where he had worked for the Coolmore empire, one of the world’s largest breeders of thoroughbreds. He was two weeks into his first stint away from home.

Doherty climbed into the cabin of a farm ute and headed back to his lodgings for breakfast. The residence was originally a confectionary store in Scone when it was acquired by Wakefield Stud to house the wave of extra staff during peak periods such as this. He parked the ute in a leeway between his home and a day yard for the stud’s mares. Beyond a large gumtree by the back door was a nightwatch paddock for mares that were expected to foal. During September, this paddock was never dark. From dusk til dawn, a series of floodlights illuminated the 2-acre maternity ward in anticipation of a birth, as most horse births occur during the cooler hours of the night.

His stomach yearning for food, Doherty got out of the vehicle and took a couple of steps towards the door of his quarters. But suddenly something grabbed his attention, a sound that was most unusual for that time of the day. Looking to his right, he noticed a lone mare in one of the day yards. She was heaving considerably and lying on her right-hand side in the short green grass.

Doherty looked around and called out to see if any of his three housemates were nearby. There was no answer. He was also aware that the nightwatch crew had long knocked off. Most of his time on stud duties had been focused on stallions, not mares. But it was too late to find a phone and dial for help. The foal was being born right before his widened eyes.

The name tag on the mare’s collar gave Doherty some comfort; she was Wiley Trade. While he didn’t know all of her details, he knew she was an experienced broodmare and wouldn’t be too daunted by her labour pains. She was owned by Brian Agnew, a prominent Sydney lawyer and the owner and operator of Wakefield Stud, and this foal was a homebred for the burgeoning operation.

The mare’s heaving became interspersed with groaning: sounds of an imminent delivery. A head soon emerged followed by two front legs, and after another almighty push the hips came out. Finally, just before 9 am, the little foal’s body was fully delivered, with the umbilical cord snapping almost instantly at its weakest point.

John Doherty had no cause for alarm. In the end, he didn’t have to interfere in any way. Having witnessed his first foaling in Australia, he headed inside to have breakfast and call the stud manager to report the news.

Half an hour later, before returning to the stallion barn, Doherty checked on the newborn. Wiley Trade had quickly recovered and the foal, a colt, was already trying to gather his feet to take his first few tentative steps. His long legs were in proportion to his body and he was a striking colour: jet black.

Once his coat had dried, closer inspection of the colt showed a white splash on his forehead. It was as if someone had dunked a paintbrush in white paint and blotted it just above the colt’s eyes. A newborn foal’s coat is not a true indication of their ultimate body colour, but most on the farm already knew that the jet-black colt would turn grey. It was in his genetics – the colt’s sire, Kala Dancer, a resident stallion at Wakefield Stud, was a grey.

Kala Dancer had a brief racing career, highlighted by an impressive victory in the Dewhurst Stakes at Newmarket in England en route to being crowned Champion European Two-Year-Old in 1984. He was purchased in 1986 by a partnership of Australian breeders including Wakefield Stud. Kala Dancer commenced stud duties in 1987, with Wiley Trade being one of his first matings.

The Wiley Trade colt immediately grew into a strapping type; lean and athletic. He was taller than most of the other foals born the same season. His eating habits were healthy and he easily metabolised his food. He was playful and cute, with an inquisitive mind, as all foals are, but this colt was proving a big hit with all who handled him. There was no hint of resentment, biting, kicking or arrogance.

By the time he was a few months old, he was the favourite among stud hands.

Weaning the colt from his mother went without a hitch. This was Wiley Trade’s twelfth foal and she was about to turn 22 years of age. She knew the drill and accepted it without resistance. She was already pregnant once again to Kala Dancer for what was to be her final foal.

As the colt grew into a yearling, his physical appearance began to alter. Tiny flecks of grey were coming through in his summer coat: his father’s influence. His jet-black days were numbered. But everyone at Wakefield Stud found him attractive, especially his owner Brian Agnew.

‘The colt had this beautiful Arab-like head,’ Agnew recalls. ‘He was also tall, leggy and athletic, had a light frame to start with. But it’s his head I remember so well. I loved him when I first saw him, but then I think everybody else on the farm did, too.’

The colt seemed to have a way with humans. He was bright, attentive and enjoyed having a stiff brush rubbed through his coat. He tied up sensibly, stood quietly around a water hose and didn’t attempt to bowl over his handler in the walking ring. It was as if an old timer’s mind had been transplanted into a yearling body. He was the consummate gentleman.

The next step was to brand the colt – a compulsory measure of identification in horses to prove who they are. With thoroughbreds, freeze branding has been the most effective method for generations, with brands placed on both shoulders. On the horse’s near side (left) shoulder is the registered stud brand – Wakefield’s brand is a W. On the off side (right) shoulder, two numbers are printed, one above the other. The bottom number is the last digit of the year of birth, which identifies a horse’s age – all foals born in a particular year will have that number. The top number represents a sequential order determined by the breeder; this is usually the order of birth but Wakefield chose to reserve the number 1 brand for what they considered to be the best foal of the season.

The discussion about who would receive the number 1 brand for the 1988 crop was extremely short-lived; the Wiley Trade colt was unanimously afforded the tag.

Since being acquired by Brian Agnew several years earlier, Wakefield Stud had grown significantly to be one of Australia’s top five vendors at yearling sales in 1990. This was primarily due to some aggressive purchasing of quality broodmares and the importation of a number of stallions to stand at stud, offering breeders a variety of options. Because of his ambition to make an impact as a commercial breeder, Agnew never seriously considered retaining the colt. Studs rely on the income generated by selling livestock to maintain the business. Emotion, and his affection for the Wiley Trade colt, had to be held back. He hoped the marketplace would fall in love with the colt as he had, thereby rocketing his auction price.

Most of the major commercial sales occur when a horse is aged between one and two – a yearling. Due to his quick physical development, the Wiley Trade colt was earmarked for the first major yearling sale of the season, the Magic Millions on Queensland’s Gold Coast in January 1990. Along with another half-dozen yearlings from Wakefield, he was prepared for the sales with specialised feeding, conditioning and educating, learning how to walk quietly and stand still for inspections, being groomed from head to toe, then finally transported by truck up the New England Highway.

Auction time is always an anxious time for a breeder. First, the rearing and preparation has to go smoothly, then the horse needs to travel well, settle into the sales complex and parade for prospective buyers. A horse that has the slightest flaw, or one that shows a tendency to be difficult to handle, could end up being passed in. Nobody wants to buy trouble.

A horse at a yearling sale is a bit like a model doing a fashion parade: they walk out of their stable, turn around and walk back, surrounded by onlookers. Dozens of times a day the Wiley Trade colt did this same walk, barely flinching. By the time the sales days started, he could have done the parade without a groom. Brian Agnew was optimistic that there may be decent interest in his number 1 colt, now a dark steely grey. ‘The horse was popular from the moment he arrived on the Gold Coast and we thought he would be,’ Agnew says. ‘He was never ill at any stage of his upbringing, he had never been lame and he had good strength of bone, although he wasn’t big boned.’

A lovely temperament, a near perfect conformation and a great pedigree page – it was all a breeder could ask for. The rest was up to the marketplace.

On Monday 15 January 1990, Lot 241, the grey colt by Kala Dancer out of Wiley Trade, entered the auction ring. It was the second day of selling, and he was the first lot of that day. As a vendor, having the first lot to go through the ring is not ideal. It’s the most subdued part of the selling day and buyers tend to be more cautious.

Casually, the colt stepped around the cramped ring in front of the auctioneer, David Chester, who quickly reminded the audience that this grey colt was a half-brother to seven individual winners and from the family of Golden Slipper winner Marscay. One can imagine the terms ‘cracking colt’ and ‘early runner’ may well have been used.

Within a minute, it was done. Bidding had rapidly reached $100,000, but no further hands were raised to continue beyond that mark. The drop of the hammer to finalise the

sale revealed a buyer who was familiar to Brian Agnew and his team at Wakefield – trainer Lee Freedman.

This was no speculative purchase; Freedman knew exactly what he was doing. At age 33, he had rapidly ascended to the top of the training ranks in Australia. Only two months earlier, he’d not only trained the winner of the Melbourne Cup, Tawriffic, but trained the second placegetter, Super Impose, as well. The quinella was a feat that had only been achieved previously by the likes of Bart Cummings. Freedman, who five years earlier had been struggling to get a winner at Warwick Farm, was now one of the most prominent trainers in the land.

Freedman signed the sales slip and headed back to the Wiley Trade colt’s stall. Brian Agnew was there waiting for him, grinning about the six-figure price, and enthusiastically shook Freedman’s hand. ‘Good buying Lee, congratulations,’ a jubilant Agnew said, beaming.

The pair had crossed paths several times in recent years, with Freedman already having a horse in training that was bred by Agnew – the colt’s sister.

‘He looks a likely type,’ said Freedman. ‘He’s athletic, well balanced, has a nice walk and should be able to run early. Who knows, we may even win the Magic Millions next year with him!’

Contrary to what many may think, Freedman explains that the colt’s price tag – which was substantial in those days – made him easier to sell on to his clients: ‘The higher-priced yearlings are expensive for a reason. There is a demand for that type of horse. In the case of this particular colt, the pedigree was solid, he was lovely to handle and he was magnificently well balanced. He seemed to move and walk so easily, he was very leggy but I could tell he still had some growing to do.

‘The clincher for me was that I trained his sister, Confederate Lady, and I knew how good she was. It made it easy for me to bid on him.’

After purchasing the colt, the trainer’s next step was to figure out who he would approach with the offer of shares. The first person he asked was the colt’s breeder, Brian Agnew. Offering a share to the breeder is not compulsory but a gesture of goodwill often displayed by the purchaser towards the vendor. Agnew was put on the spot but Freedman allowed him some time to think about it while the rest of the stud’s yearlings were sold that afternoon.

Among the large gathering at the sales complex that day were two of Freedman’s existing clients. David Kobritz had wandered in out of curiosity while holidaying with his family on the Gold Coast. He knew nothing about the colt until he found Freedman just outside the auction ring. The Melbourne property developer and investor suggested to

Freedman that if there was a horse that the astute trainer really liked, he could be tempted into taking a share. Immediately, Freedman began ushering him towards the stall that housed Lot 241.

Fortuitously, Angelo Torcasio crossed paths with the pair en route and decided to head in the same direction. Kobritz and Torcasio were introduced to one another and realised that they had a bit in common: Torcasio was also a property developer. He had recently placed a horse with Freedman to train for the first time. It was so slow that nobody remembers the horse’s name.

The Wiley Trade colt was led out of his box to parade one more time. Having repeated this exercise hundreds of times while at the sales for nearly a week, the colt was carrying his head a bit lower. He looked a little tired and almost bored. The Queensland sun glared in the men’s faces as Freedman explained the pedigree and the reason for his purchase. It wasn’t a hard sell. Even though each had been affected by the stock market crash of 1987 and business was still recovering, Kobritz and Torcasio had a passion for racing. The thrill of winning and the anticipation of doing so kept them in the game. When Australia’s hottest trainer recommended that this was the horse for them, it was a temptation that neither could resist. They all shook hands and agreed to finalise arrangements later.

Brian Agnew soon returned to crunch numbers with Freedman. The proposal was for four, perhaps five, partners in the colt. As much as he adored the horse he’d bred,

Agnew, after some agonising, decided to cash the surety and bank his $100,000 sales cheque. It was sound business logic for the breeder.

Upon returning to his hotel that evening, Lee Freedman knew he’d have another taker. Melbourne businessman Peter Alpar had raced a number of horses with Freedman in the previous five years with mixed success. Alpar had already asked the trainer if he could inspect the Kala Dancer colt after Justin, Peter’s son, had found the listing in the sales catalogue. The Alpars were keen to be in and might have purchased the colt outright had he been sold for less than six figures. Instead, they decided they would race the horse in partnership with others.

Freedman now had a commitment of up to $25,000 from David Kobritz, Angelo Torcasio and Peter Alpar. One more partner would be enough and he didn’t have to think too hard to find that person.

Only the previous evening, Freedman was introduced to Gold Coast car salesman Alan Brodribb at a dinner party. The jovial local made himself known to the trainer and left his business card with an instruction: ‘If you find something decent, I’ll take a leg.’

After a brief conversation with Brodribb, Freedman had stitched up the deal. The four businessmen became equal shareholders of a dream. That dream, as it had been sold to them, was the prospect of winning the feature Magic Millions two-year-old race on the Gold Coast in twelve months’ time. Based on the performances of Confederate Lady, it was an entirely achievable aim. The investment promised quick returns and the businessmen were all for it.

Transportation for the colt had been arranged along with Lee Freedman’s other purchases from the sale, and the two-day drive from the Gold Coast back to Victoria began. As this was happening, the ownership party convened a meeting to discuss a very important aspect of their latest acquisition: his name.

The four owners had all made far more important decisions in their lives than naming a horse, but unanimously decided that a $100,000 purchase price compelled them to agree on a suitable name. It was important to them that it should be simple, easy to read and understand. Discussions were conducted in person wherever possible, but all four were busy with businesses and Brodribb lived on the Gold Coast, which made things difficult. A phone hook-up was usually necessary.

A number of names were raised. Some clicked with a couple of the guys, but not all. A few names were submitted, but rejected by the registrar because they were already in use. Something that should have been relatively straightforward was becoming quite a chore.

Alan Brodribb had an idea. He’d recognised that many of the best horses in Australian racing had a name comprising seven letters – including Phar Lap, Carbine and Tulloch – and it’s considered to be lucky. Fortune, after all, is a seven-letter word. So Brodribb wrote down several names, all with seven letters.

Eventually, the ownership group agreed on another list and it was submitted. They soon received news from the registrar that a name had been granted for the grey colt by

Kala Dancer out of Wiley Trade, foaled in 1988 – it was one that Brodribb had suggested. Part of the name came from the mother of Kala Dancer, a mare called Kalazero. The other was a three-letter prefix attached to form the seven-letter word which would hopefully represent good luck for the team.

From the day the letter arrived, the colt was known as Subzero.

Subzero Adam Crettenden

The story of Subzero, one of the most popular horses in Australian history.

Buy now