- Published: 18 October 2022

- ISBN: 9780143778257

- Imprint: Penguin

- Format: Trade Paperback

- Pages: 208

- RRP: $34.99

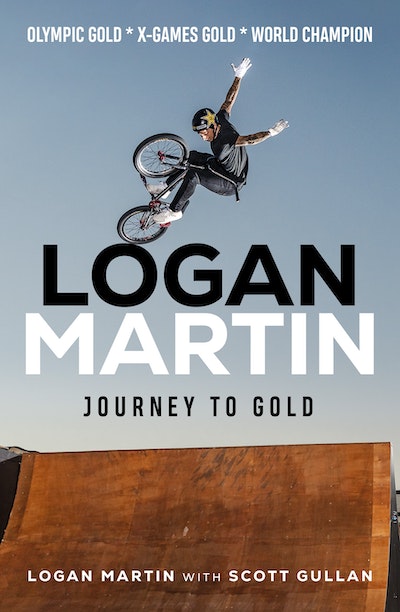

Logan Martin

Journey to Gold

Extract

LEARNING TO FLY

I always wanted to tackle the big kids.

Someone told me once that the best way to tackle an opponent on the Rugby League field was to take out their legs, because then they couldn’t run. That was instantly wired into my brain, so from that moment on, every time I’d make a tackle, I’d take the legs. And I’d do it even though I was the smallest player on the field. In fact, that was almost my badge of honour: I never let my height, or lack thereof, stop me from doing anything.

It was like a chip on my shoulder. It made me even more determined to show people that I could do things.

From the age of six, when I first started playing rugby, that was my attitude. You’d often see kids too scared to go at the big kids, but I threw caution to the wind and didn’t seem to care about what happened. I just went at them. Take the legs.

It was an attitude that would serve me well, although, despite my love for the game, Rugby League didn’t turn out to be my sport.

I grew up in Logan City, Queensland – yes, I was named after the place, but more about that later – and played with three junior clubs around the area, beginning with Waterford before moving to Logan Brothers, which was famous for producing many NRL stars, including one of the greatest of all time, Melbourne Storm’s Cameron Smith.

I played as a hooker because my ball control and awareness on the field was good. At my third club, Beenleigh, we had an above-average team that made the local grand final, but then a new coach came on board and I found myself on the outer as he played favourites with his son and some of the Islander boys.

The smallest kid was always the first to go, no matter how good they were in junior teams. I was only getting on for five minutes here and there before being benched again. I didn’t want to be a part of that, and my parents agreed, so at the age of twelve my Rugby League career was over.

Despite this setback, playing sports was my passion, and it would come as no surprise to learn that my favourite class at school was HPE (Health and Physical Education). That’s the one class where I’d listen intently to the teacher and always do my best to impress them. I was a dynamo at school sports; I seemed to be able to pick up different sports quite quickly. My motivation was simple, even back then: I just wanted to be better than everyone else. Whether that was in the swimming pool or even on the gymnastics floor, I wanted to be the best.

This desire to be the centre of attention on the sporting field was ironic in a way because generally I was a shy kid who didn’t have too much to say. But there was something about being good at sport that gave me an identity. For some reason I always felt like people expected that I would be good. There was actually no reason for me to think that way. It might sound crazy, but in my mind I wanted to prove that to be right. The problem was, with rugby out, I needed to fill that void.

The unexpected solution came when my parents moved us into a new rental on Augusta Street, Crestmead.

My brother, Nathan, was a year older, and I was your typical annoying younger brother, following him everywhere. Every now and then he’d go down to a local skatepark and ride his BMX around. That was my first introduction to the sport.

Our new house in Crestmead was just a block away from the park, which was a magnet for young teenage boys wanting to hang out. Nathan was quickly drawn in, with his little brother always a step behind. Obviously I needed to look the part, so for my next birthday I asked for a BMX of my own.

My first bike was a small 16-inch frame ABD green machine, and the day after I got it Dad, Nathan and I went down to the skatepark. Next to all the ramps was some grassy park area, and I was riding around there when I crashed. I’d turned too fast and put it in the dirt, but the problem wasn’t what happened to me – it was the massive scratch I’d just put on my new bike.

I was devastated. I couldn’t believe I’d ruined my pride and joy on one of the very first rides. Time healed that wound, and soon I was going down with Nathan all the time to ride in the park.

The Crestmead Skate Park had a little bit of everything for BMX riders and skaters. There was a round bowl; a cornered, three-sided bowl; quarter-pipes; a half-pipe; stairs; rails; a fun box; ledges; pyramids and big banks.

It was quite daunting for a beginner, but we slowly got the hang of it, and the first trick I learned was called a fakey, where you’d go up the quarter-pipe straight, then ride down backwards and spin around.

This was all happening around the time I started high school, so I was making new friends and they were all going down to the skatepark, which became our hang-out spot. There weren’t many skateboarders down there; it was all about BMX and scooters.

After a few months it was obvious my bike was quickly becoming too small, but instead of looking at a new BMX, I made a detour into the scooter world. They’d become all the rage, so with a few mates we all switched over for about six months. You could obviously throw them around for tricks, but they weren’t suited to practical things, like getting to the train station, so the enjoyment faded.

This corresponded with Christmas approaching, and I turned my attention to raising the funds to buy a new, bigger and better BMX. I started mowing the lawns on the weekend, which would get me twenty bucks from my parents, and by the time Santa Claus was getting ready to do his thing,

I’d saved almost $300. My parents generously agreed to chip in the rest for the bike I’d chosen: a 20-inch GT Transformer. It was a thing of beauty with a white frame, blue handlebars and blue forks.

It was exciting to be back on the bike, although I soon realised it was a little bit heavy. Obviously to do tricks on a BMX the lighter the bike the better, so I again started saving my money, this time for lighter parts to upgrade my Transformer instead of getting a whole new bike. For most kids, getting twenty dollars for doing odd jobs would be gone within hours, usually spent on junk food. I’d learned from a young age to use my money wisely since my parents were forever telling me to use your money for what you want – don’t waste it.

By this stage I’d lost Nathan – lost in the sense that he was no longer into BMX. He’d had a big crash that knocked his tooth out and never went back. He couldn’t shake what had happened and became scared of crashing.

Getting hurt never entered my mind, even after what had happened to Nathan, and instead I went the other way, spending every spare minute down at the skatepark. My daily routine would have Mum picking me up from Marsden State High School, which was about a five-minute drive from home, at 2.45 pm. I’d race inside, change out of my school clothes, quickly have something to eat and by 3.15 pm I’d be at the skatepark, where I’d stay until it was nearly dark.

On weekends we would take the train to Beenleigh, which was only ten minutes away, to the best skatepark in the district. When you first lay eyes on Beenleigh you think you’ve found your skating nirvana – there are ramps, banks and walls everywhere. Big ones, small ones, tall ones – all shapes, all sizes – end to end and ongoing.

There was a really good BMX scene there, given that two of Australia’s best professional riders had learned their craft at that park.

The pinnacle in BMX competition was the X Games. It was an annual extreme sports event in America organised and televised on ESPN. It was watched by millions around the world and featured the world’s best BMX riders, skateboarders and motocross riders.

Colin Mackay was regarded as the first Australian rider to make a career out of BMX in the US, and he was a regular X Games competitor while Ryan Guettler followed him shortly after and won two X Games bronze medals. Both were local Beenleigh boys, which meant I literally now lived just down the road from the home of BMX in Australia.

The only way to learn new tricks was either copying someone who was better than you at the park or spending hours watching YouTube videos. The fact Mackay and Guettler had made the big time from the same town gave us all a boost. If they could do it, why couldn’t we?

There was a crew of six of us – Jake, Levi, Johnno, Connor, Justin and myself – who were either hanging out at the skatepark or at each other’s houses. Every weekend we’d be inseparable, riding the train line and stopping at various skateparks around Logan.

We were enthusiastic fifteen-year-olds, but we had a plan: ‘If we learn a trick every day, how good are we going to be when we’re twenty?’

The Under 16s competition at Logan Village Skatepark was my first career victory.

A small trophy, which I still have somewhere, was my reward for a run that consisted of some basic tricks, such as one-handers, no-footers, 360s and footjams. Soon I graduated to bigger events and bigger tricks, but to do that you had to get inventive.

Learning how to do a backflip was a key moment, and while you’d practise that now into a foam pit at an indoor facility, those things weren’t available back in the day in Logan.

This is where Dad came to the rescue. He would travel around the neighbourhood collecting old mattresses that people had put out on the nature strip to be taken away as hard rubbish. While my parents didn’t know a lot about BMX, they were always supportive, transporting me and my mates to competitions. But the mattress collecting was a crucial role.

Dad would bring them down to the skatepark and place them on the ramps for safety. It was easier to learn a backflip on a scooter first, because you had to get used to that feeling of being upside down. The scooter is a lot lighter, so it’s easier to flip. There’s also nothing in between your legs, obviously, so you can jump off to the side and land on your feet if something isn’t right.

The backflip is all about commitment. Once you overcome the fear, it really isn’t a hard trick.

When it came time to learn on the BMX, Dad brought down three mattresses and a wheelbarrow, which he used to move some sand from the nearby sandpit over to the ramp to help soften the landing even more.

On my fourth attempt I nailed it and actually flipped over the mattresses and landed on the grass bank. It was a significant moment because not too many people around the local area were doing backflips. Unless they had a private set-up in their backyard, which was very rare, there was nowhere to learn them.

Each new trick had a different story. The tailwhip – which is when you hold onto the handlebars and kick the bike around and then land back on it – took a long time to nail. My mate Jake Manning was further advanced than me, but he could only get one foot back down on the pedal on landing, not both.

This dragged on for six months for him, and one day after school at Crestmead I decided it was time that I really zeroed in on the tailwhips. After a couple of hours it felt like I was getting close, but we needed something more so we headed to Beenleigh the next weekend for the bigger ramp, which would give us the height we needed.

That afternoon we both landed tailwhips. It was a great moment, and I was particularly pleased given that what had taken my mate six months had taken me just one week.

Not all our learning went that smoothly.

As our thirst for new tricks and continued improvement began to rise, we started travelling to better venues and became regulars on the train to Brisbane, which was only thirty minutes away. We had access to a foam pit there, which was the safest way to learn big-time tricks, such as frontflips.

Luckily, after a couple of sessions the guys who ran RampAttak, the indoor skatepark in Brisbane, liked what they saw and generously offered free access to the facility. It was such a big help, and after a weekend of doing frontflips into the foam, I decided after school I wanted to try one at my local skatepark. I was convinced I was ready for that step, but unfortunately I wasn’t. On my first attempt I didn’t rotate all the way around and landed more on my back wheel, smashing up my ankle in the process. It was pretty bad, and

I had to be on crutches for a couple of weeks at school.

The dynamic at school was an interesting one. Rugby League was clearly the number one sport, and they had a really good program at my high school. There were two cool groups at school, the rugby boys and the skatepark crew, and we sort of kept to our own. We didn’t mess with their business, and they didn’t mess with ours.

It was around this time that I became convinced my time as a student was coming to an end, and after completing

Year 11 I decided Year 12 wasn’t required. My mum didn’t agree. She was always very strict about missing days of school and never cut me any slack on that front.

‘Unless you have a job, you’re going to Year 12,’ she declared.

My brother had left school early; he didn’t get through Year 11 as he’d lined up an apprenticeship as a painter. He did that for a year or so, but I was more keen on carpentry. After much thought, I decided to stick with school, but I’d come up with a plan. I was starting to get pretty good at BMX to the point where I was winning a lot of local competitions.

There was an event called the Core Series, which had several stops around Brisbane throughout the year. I’d started entering the pro category, rather than sticking to my age group, with the aim to accumulate as many points as possible at each event. The series winner was the one with the most points at the end of the year. There were usually about fifteen to twenty riders, with qualifying and finals on the same day. You’d do two qualifying runs then wait an hour or so and do two more in the final, with the best run counting.

The prizes for winning a stop were usually a voucher to a bike shop or parts for your bike. The grand prize at the end of the year was a cheque for $500. I won the series twice by the time I was sixteen.

While it was nice to win I didn’t see that as a turning point in my career, although that did happen around that time. And it was all about a trick.

The flairwhip – a backflip with a tailwhip – was one of the biggest tricks going around. I had spent hours every night watching the professionals doing them on YouTube. My theory was that if I could learn this trick and get comfortable doing it every day, to the point where I could do it in competition, then that would put me on the same level as the pros.

It was a slow process, but I broke the trick down and focused on each part. I could do flairs, I could do backflips into the ramp, I could do backflip tailwhips over a box jump – the ingredients were all there.

When I started delivering the trick I was only sixteen, which was very young for someone to be pulling off such an elaborate trick, one that the pros were performing at the

X Games. I’m not saying I was the youngest person to ever do it, but it was the trick that had people starting to take notice of my skill set.

It raised the question: what was next?

I had a decision to make, and it would be the one that would shape the rest of my life.

Logan Martin Logan Martin

Olympic gold medalist, X-Games legend and world champion Logan Martin shares his inspiring journey to the top of the BMX freestyle podium – the art of flight and the lessons of gravity, the pursuit of perfection and the pull of family, the sacrifices required and the simple joys of a backyard session.

Buy now