- Published: 17 August 2021

- ISBN: 9781761043437

- Imprint: Penguin

- Format: Trade Paperback

- Pages: 336

- RRP: $34.99

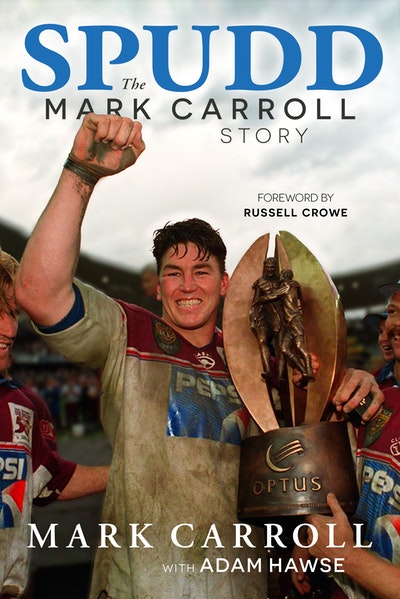

Spudd: The Mark Carroll story

Extract

MG and Gus had won a premiership together at the Panthers in 1991, but things became strained for a number of reasons and Geyer left the club to join Balmain.

For whatever reason, MG missed the first training session and, after turning up late for the second session, was dumped from the team by Gus.

MG, who loved a stink, was not amused. ‘I’ll have you outside!’

An unflappable Gould didn’t bat an eyelid. ‘Well . . . don’t let fear hold you back.’

And there it is. The quote I use on a daily – sometimes hourly – basis to motivate my clients. Not just at the gym, but also via text messages and emails. It annoys the hell out of them and I mix the words up a bit to get my point across.

‘Don’t let a sniffle hold you back.’

‘Don’t let crap weather hold you back.’

‘Don’t let slow traffic hold you back.’

You get the picture.

Looking back at my playing days, that quote from Gould sums up the way I used to go about business. To be a front row forward in the toughest competition in the world, you can’t have fear. There’s no time to be scared. If you feel that way, you’re not going to make it very far.

That is how I played rugby league. Every run I made was coming off the back fence, because the harder I ran, the less chance of coming off second best when bodies collided.

Sure, I spilled plenty of blood and tears, and broke some bones along the way.

But I feared no-one.

KICK-OFF

The ball is high in the air and the only thing going through my head is the 20 metres. That is, the 20 metres I have to run before I get pulverised by four or five blokes just as big as me. It’s the moment I’ve been waiting for all week – when the game kicks off and I take the first carry. To me, it is the toughest run not just in rugby league, but world sport.

The only thing I can compare it to is a car crash. Without the airbags. Two objects colliding at high speed, with no bracing for impact.

Sure, the NFL boys in America throw themselves at each other, but they are wearing huge helmets and fibreglass shoulder pads. There’s none of that protection in rugby league.

As scary as it sounds, this moment meant everything to me.

Whichever club I played for – Penrith, Souths, Manly or the London Broncos – I insisted on taking the first run of the match. Even when playing State of Origin for New South Wales, I’d say to one of the game’s truly great front rowers, Paul ‘Chief ’ Harragon, to leave the first carry to me.

If I didn’t get it, I’d be filthy on the world.

Taking that opening run gives a front rower the chance to impose himself on the game with his very first touch. When I wear the number eight or 10 jersey, it’s all about physicality and showing no fear.

It begins from the moment I turn up at the ground, hours before the game is due to start. If I see my opposite number pull up in his car, or climb off the team bus, there’s no ‘hello’ from me. Not even a nod in his direction.

I don’t care if it’s an old mate like Peter Johnston or Les Davidson. Hell, we are about to go to war. There’s no time for a smile.

When the referee blows the whistle and the kicker strikes the ball, I’m in the perfect headspace. I make sure I’m in position to catch it or at least take a short pass from a teammate.

Then it’s time for that 20 metres.

My back foot is on the dead-ball line, the deepest I can be without being out of the actual field of play. This gives me as much space as possible to wind up and run as hard as I possibly can.

Once that footy is under my right arm I only have one objective: to reach the white chalk of the quarter-line. This is located 20 metres from the goal-line, which is roughly where I catch the ball. By now I’ve hit top speed, but so have they. I look up and there’s about four or five of them, sometimes more.

While the first carry sets the tone for the attacking team, the first tackle sets the tone for the defending team. So, I know they want to hurt me. They want to stop me in my tracks, get under my ribs, and drive me back to where I came from.

Bring it on.

You probably think I’m mad. Who in their right mind would volunteer for such a role? Like an opening batsman sticking his hand up to face the new ball against the mighty West Indies attacks of the 1970s and ’80s.

When we come together the force is immense. I wish they could measure the impact with sensors or something, because I reckon the numbers would be mind-boggling.

Despite the carnage and the roaring crowd, I keep the legs pumping and my eyes fixed firmly on the white chalk. It helps to focus on something as my body is being twisted and pulled in all directions.

I never cared who was in the tackle – I always made that quarter-line. If I was feeling really good, I would sometimes look beyond that 20 metres to where there might be a sponsor’s logo painted on the turf. Pepsi sponsored Manly back in the 1990s, so I’d aim for the ‘e’ as a place to land.

Covering a distance of 20 metres might not sound such a big deal.

To me, though, it was everything, because it gave my team the ideal platform to start the game.

That was my job. But there was so much more still to do.

NOT SMART ENOUGH FOR SOCCER

Rugby league has always been a massive part of my life. You know that cliché, the one where someone supposedly ‘lives and breathes’ whatever their passion might be? Well, that was me.

I was born and raised in Greystanes, one of the oldest suburbs in Sydney, located just west of Parramatta. It’s very much working class and rugby league heartland. I should know – I spent the first 26 years of my life there with my parents and younger brother and sister.

Parramatta Eels legend Ray Price lived just around the corner. Like plenty of other kids from that generation, I spent many hours trading footy cards, and if you had a Pricey card, that was huge. Queensland icon Wally Lewis, ‘The King’, was also in demand. You’d need five Stan Jurds – the burly Eels forward – to get one Wally.

We lived in Bradman Street and, yes, it is named after Australia’s most famous sportsman. Actually, it’s strange I didn’t become a cricketer, because all around me were some of the biggest names in the game.

Just down the road was Lawry Street and Benaud Street. There was Simpson Street and Grimmett Street as well. All legends of the bat and ball game.

Out of footy season I did actually play a lot of cricket. Every week my brother Dean and I would push a lawnmower to the local park with our friends and mow a pitch in the middle.

I was a fast bowler who also loved to hit a long ball. To anyone from Greystanes who found some broken roof tiles on their house back in the early 1980s, please accept my apology. I loved to give that ball a whack.

One Christmas I received my first ever cricket bat from Santa, when I was about nine. It was a new Slazenger, completely decked out with protective plastic covering. No need for endless hours oiling the thing, like the older style bats. This was ultra-modern and I was so excited. I couldn’t wait to put some cherries on it.

But first it was the obligatory Christmas Day street cricket match, and up stepped Uncle Al. He was pretty excited by the bat too and insisted on having a go with it.

I fired in a short ball and Uncle Al swung hard – and lost his grip on the bat. The shiny, new Slazenger went soaring through the air as my jaw suddenly hit the bitumen. The bat slammed into a roadside railing and a huge chunk of timber came flying off. It was ruined and I was devastated.

I cried and carried on like a pork chop. Poor Uncle Al was mortified. I reckon if I’d pushed a bit harder with the tears, I could have picked up two or three new bats that day. Everyone was offering to buy me one!

Like most kids, the bat I always wanted was the Gray-Nicolls Scoop, made famous by the Chappell brothers. It was a cricket bat with a long scoop running down the back. A radical change to all the traditional bats on offer and top shelf at the time.

And, sadly, out of my budget.

So, I made one myself. I grabbed Dad’s chisel from the garage and gouged out a long strip of timber from the back of my bat (the one that had replaced the poor old Slazenger).

Bingo! My very own Scoop.

I took it across to the park with a new six-stitcher red ball to get some cherries on it. First hit – snap. The bloody thing broke in half. That was the end of my bat-manufacturing career.

In those summer months I was also really keen on athletics and quite good at it. In fact, I believe I still hold the record at Greystanes Primary School for the quickest 100 metres. Not bad for a bloke who went on to play in the front row!

When I moved on to Greystanes High School I continued with athletics and actually beat a guy named Miles Murphy, who later competed at the Olympic Games as a sprinter. He also won a silver medal in the relay at the Commonwealth Games.

I did it all barefoot too – my feet are so big they couldn’t find any spiked shoes in my size. While my competitors would have their own starting blocks and spikes, I’d take them on with my bare feet. I remember once running at E. S. Marks Field in Kensington, which is ringed by a blue-coloured running track. When I finished, I looked down and my feet were completely blue!

I made it to state level, but wasn’t quite good enough to go any further. Back then the coaches would push you pretty hard and you’d often run the 100 and 200 metres, plus do shot-put, long jump and high jump all in the one day.

When they made me do the 1500-metre race as well, I went home to Mum and Dad and told them I was done. It was too much and the enjoyment was gone. Which just meant more time for footy!

Dean and I would go down the road to my friend Mark Hatcher’s place for a game in his backyard every afternoon. Our yard was too steep, so the Hatchers’ was a better option.

It was an L-shaped playing area, which meant one end had a longer try-line to defend. Dean and I would always back ourselves and take that end, sometimes going up against five other boys. We usually won, although Mark and another mate, Alan Reanie, might disagree with that memory!

It didn’t matter if it was pelting rain, we’d play in all conditions. One day the backyard was soaking wet and we were slipping and sliding all over the place. Pretty soon the turf was ripped to shreds.

My parents, Dave and Eileen, were huge inspirations for me. Mum can actually take a lot of the credit for me becoming a rugby league player. Being a Pommy, born in Manchester, Mum knew far more about the Red Devils than she did rugby league. When it came to picking a sport for her little Mark, it was the round-ball game. Soccer. Or football, as the purists remind us.

Like anyone else, my memories as a four-year-old are pretty sketchy. But I do remember not enjoying soccer. Probably the thing I loved the most was getting a nice new pair of boots! How good was that?! While the other kids were trying to put the ball into the back of the net, I could be found digging holes in the turf with my beloved footwear. It was the best thing about Saturday mornings.

Eventually Mum said to Dad, ‘All he does is run around in circles and dig holes. I don’t think he’s got the brains for soccer – maybe he should play rugby league.’

Mum denies saying it in those words, but she was on the right track. I was no soccer player.

So that’s how I made the switch to rugby league, and in Sydney’s western suburbs there was no shortage of junior clubs to choose from.

In that era the Eels were absolutely flying. After becoming a force to be reckoned with in the late 1970s, they swept all before them in the ’80s with an exciting brand of footy under the original ‘super coach’, Jack Gibson. A golden era for the club and the NSW Rugby League in general.

Ray Price, Eric Grothe, Mick Cronin, Brett Kenny, Steve ‘Zip Zip Man’ Ella and Peter Sterling – they were all heroes of mine. They won three straight comps in 1981–83 and another in 1986, captivating a generation of youngsters just like me.

It seemed like every kid was getting around in a blue and gold jersey, that’s how popular they were. You couldn’t afford a team like that now because of the salary cap. The Eels of the early ’80s were a once-in-a-generation team and you wouldn’t find a bigger fan than young Mark Carroll from Bradman Street, Greystanes.

I started off with the Guildford Owls (Brett Kenny’s junior club) when I was a seven-year-old. Their home ground, McCredie Oval, had the highest goalposts in the southern hemisphere and the challenge for all kids in the neighbourhood was trying to kick the footy above the uprights. You needed a bloody decent kick to do that and, being so young, I had no chance. I was mesmerised by these goalposts and became instantly hooked on league.

After starting out with Guildford, I also played for Wentworthville and Hills District. I collected a lot of trophies as a kid and I still have all of them. Loads of them. I just love trophies.

In those early years, positional play isn’t really a thing, you just catch the ball and run wherever you feel like, preferably toward the opposition try-line.

As I grew older, I moved into the halves, in particular five-eighth. That might sound strange given my reputation as a front rower who enjoyed the rough stuff. Back then my passion was the chip kick, the cut-out pass, the kicking for line. I was more Peter Sterling than Stan Jurd.

I was in the Parramatta system this whole time, so getting picked for the Eels’ junior rep teams seemed like the next step for me. Our under-14s team at Hills District was unbelievably good. We wore a black jersey and black shorts, which really did signify a dark day for the opposition. Like rugby’s All Blacks, we were almost unbeatable.

One of our stars was a kid called Mark Blackburn. A great player – with an even better beard. At 14! I said to Dad, ‘When am I going to get a beard?’ Dad said my time would come. Well, Dave, I’m still waiting decades later! Just can’t grow a decent beard.

Anyway, back to Mark Blackburn. He was a freak and, even as a big forward, could kick goals from halfway. He went on to play junior reps at the Eels and then first grade at St George and Souths.

We had a lot of fun at Hills District and we won the under-14s competition easily. Next up was something called the Coca-Cola Challenge Cup, a knockout tournament featuring the best teams from around Sydney. We won that too, which was great – but the best was yet to come.

Each kid from the winning team was presented with a bright red jacket and splashed across the back in large white lettering was the name of the sponsor, Coca-Cola. I was like a pig in shit wearing that to school the next day!

In my opinion, without blowing my own trumpet too loudly, I reckon I was up there with the better players in the competition that year. But I got shafted.

When the coach’s son got the nod ahead of me for Parramatta’s Harold Matthews team (under-14s), I was stunned. I had been winning awards all season for best back and best trainer, yet it still wasn’t good enough. It left me in tears – and I vowed to make Parramatta pay.

Spudd: The Mark Carroll story Adam Hawse, Mark Carroll

The long overdue autobiography of Mark “Spudd” Carroll is one of the most fearsome players to ever lace on a boot.

Buy now