- Published: 21 July 2020

- ISBN: 9780143795766

- Imprint: Penguin

- Format: Paperback

- Pages: 384

- RRP: $26.99

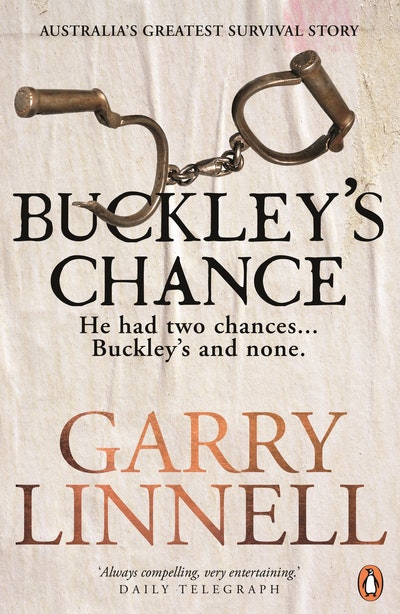

Buckley's Chance

a new era of Australian non-fiction storytelling

Extract

Part of the problem is that so many people insist on peering into history through a modern lens, applying the standards of the present to the past. Because of this, Buckley’s legacy leaves many feeling uncomfortable, in the same way the man’s imposing physical presence made those around him feel uneasy. He made some awkward observations about the black and white worlds in which he lived. Both societies could be cruel and inhumane. He lived in a time when Indigenous people were labelled savages and their presence seen as an impediment to so-called progress. He also lived in a period when orphaned white children were treated as slaves and where unspeakable atrocities were carried out on the poor and defenceless. Buckley was consigned to a no-man’s-land between these two vastly different cultures. Was he a traitor to the Aboriginal people? Or did he betray white people?

So much about the man is in dispute. Even etymologists, that diligent band who study the history of words, do not unanimously agree on the true origin of the phrases ‘Buckley’s chance’ and ‘You’ve got two chances – Buckley’s and none’. Some have suggested it may be a play on ‘Buckley & Nunn’ – a Melbourne department store first established in the early 1850s. But the weight of opinion now leans heavily toward the man as its source. By the early 1870s there was a racehorse called Buckley’s Chance and the phrase itself was being used in print by the 1880s to indicate long odds.

What is not in dispute is that this man led one of the most extraordinary lives imaginable. Which is what this book is about. Even by the standards of the 18th and 19th centuries, when epic feats of endurance and courage were commonplace, his tale still borders on the unbelievable. He fought against Napoleon’s army. He endured the hell of England’s festering prison hulks. He was shackled for six months while being transported to Australia. He escaped and was adopted by the Wadawurrung people. And then, more than three decades later, he returned to live among white people as they set about seizing Aboriginal lands and doing their best to erase from existence the world’s oldest continuing culture.

I grew up in Geelong and heard tales about the so-called Wild White Man. But they were just stories. No-one I knew had any real idea who he was or that he had ever really existed. I have no memory of learning about him in school, which is no surprise given the unimaginative and embarrassed manner in which Australian history is often imparted in our classrooms.

All I knew was that a huge and immensely strong man with a long beard and a spear in his hand had apparently spent decades roaming the nearby countryside.

Family outings sometimes found us at Point Lonsdale, staring up at the gnarled, wind-whipped sandstone cliffs where Buckley’s Cave sits beneath the lighthouse, its tantalising entrance barricaded to discourage vandals and amorous couples. The site has long been dismissed as nothing more than an imaginative attempt at attracting tourism. But recently my uncle, Ken Bell, came across a letter written by the Irish botanist William Henry Harvey when he was in Australia in the early 1850s. Harvey writes about finding a small cave at Point Lonsdale and ‘it is said that Convict Buckley, who first explored these parts, lived there when he first landed as a runaway’. There were no tourism spruikers in 1853, so it seems probable that the cave actually was used by Buckley. Let’s hope they take down the iron bars protecting the cave and look at opening it to the public.

William Buckley seems to be riding a new wave of respectability he could never have imagined. In 2018 several original documents relating to his discovery by John Batman’s party sold at auction for more than $40,000 – far more than papers written by Batman and other more prominent explorers. He has had a beer dedicated to him and numerous trails and locations in and around Geelong now carry his name. Why, all the man needs now is an Instagram account . . .

In life no-one ever quite knew where William Buckley stood. In death we have no idea where he truly lies. In Hobart, a small grove of maple trees and newly laid lawn form Buckley’s Rest, a quiet corner in a busy section of Battery Point. He was buried around there in 1856. But a large primary school now sits on the site of the old bone yard and the small park commemorating his life is about as physically close as anyone will ever get to him.

Which brings us to this book. Buckley’s Chance is not a conventional historical biography. William Buckley’s life rubbed up against events and characters that changed human history. I was staggered by just how many there were. Along the way I fell in love with the 19th century. Despite its cruelties and racism it was the last true epoch of human exploration on this planet. It produced an unprecedented array of the brave, the stupid, the reckless and the appalling. It also inspired mountains of excessive verbiage, which is why some have dubbed it the ‘Era of Windbags’. Read many of the memoirs and journals of the day and you will discover writers who relentlessly hurled commas at their pages like darts, who capitalised every noun with compulsive obsessiveness and were skilled in the unfortunate art of telling any short story long. Because of this I have made some grammatical changes to quotations in order to make them easier to read by 21st century standards. Any conversations quoted directly have either been sourced in the text or in the Endnotes.

There are more than one hundred variations on the spelling of ‘Wadawurrung’. I have chosen to use the most commonly accepted form, along with other Indigenous words and phrases. A book like this leans on the work of many. But my biggest thanks must go to my wife, Maria. Patient as ever, she was always there, even when I wasn’t. And when I was there, my mind was often adrift in the first half of the 19th century. William Buckley certainly took his chances. But Maria took the greatest chance of all and I love her for it.

Garry Linnell, October 2019

Buckley's Chance Garry Linnell

<h3>From Walkley Award-winning writer, Gary Linnell comes the greatest Australian story never told - until now.</h3>

Buy now