- Published: 6 June 2023

- ISBN: 9781761342356

- Imprint: Penguin

- Format: Paperback

- Pages: 576

- RRP: $26.99

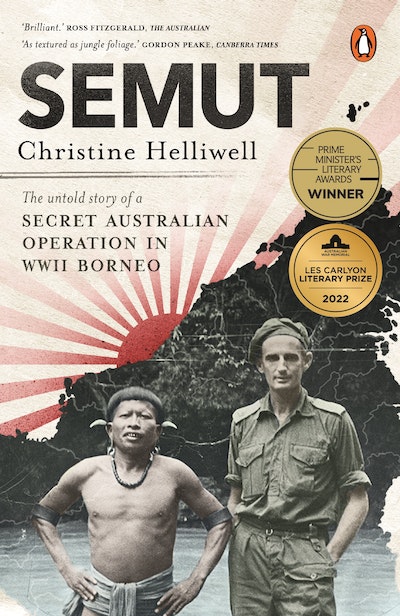

Semut

The Untold Story of a Secret Australian Operation in WWII Borneo

Extract

I first met Jack in 2014 when I visited his home in Adelaide to interview him after learning he had taken part in a World War II (hereafter WWII) Allied special operation in Borneo. Although I had been carrying out research on WWII in Borneo for some time, Jack was the first Allied soldier I interviewed. I flew to Adelaide in September of that year, accompanied by a videographer from the Australian War Memorial (AWM). I was thrilled to be meeting someone who had travelled through Borneo’s astonishing jungles in the 1940s, long before the terrible destruction inflicted on them in later years by rampant logging and the establishment of vast palm oil plantations. I had first gone to Borneo in the 1980s – forty years after Jack – as a young woman looking to conduct research for a PhD in anthropology, and had lived for twenty months in a longhouse in the jungle, studying the social and cultural life of its Dayak inhabitants. Like Jack it had been my first time outside Australasia. I have spent a lot of time on the island in the years since, but never forgotten my first few months there.

As we settled down in Jack’s immaculate living room under the eye of the video camera and his family photos, I asked him about the Borneo jungle. ‘I thought,’ he said, ‘that it was the most beautiful place on earth.’ And so began our friendship, forged over a shared love for a tragically disappearing place.

In early 2016 Jack and I joined forces to lobby the AWM to install a plaque on its grounds honouring Z Special Unit, the name by which Jack knew the Australian secret military organisation with which he had fought during WWII. Like all Z Special Unit personnel, he had signed secrecy provisions, and during his postwar debriefing he was ordered to remain silent for the next thirty years about his activities with the organisation. Other, although by no means all, Z Special men received similar orders – some even being sworn to secrecy for life. Many obeyed and, as a result, in large parts of Australia there were no Z Special Unit veterans’ associations until the 1970s; in the absence of a Z Special banner, Jack marched with the 1st Australian Parachute Battalion each Anzac Day. The organisation’s lack of visibility meant that it was one of very few from WWII never to have been honoured with a dedicated plaque at the Memorial.

Memorial approval for the plaque was quickly received and I began a search throughout Australia and overseas for Z Special personnel and their families, hoping that many would travel to Canberra for the dedication ceremony. This was a crazily ambitious undertaking since the organisation’s recruits had come from several countries and few up-to-date contact details were available. In addition, those who remained would now be very elderly and likely to find travel difficult. But finally on 1 August 2016, after seventy years of waiting, more than twenty aged veterans and around one thousand family members gathered opposite the AWM sculpture garden (a group even having crossed the Tasman Sea from New Zealand) to honour and remember. Many of those who attended had lost husbands, fathers, grandfathers, brothers, uncles and friends to the organisation’s notoriously perilous operations, and had made the trip to lay their grief to rest. As the Ode was read and the melancholy strains of the Last Post sounded across the Memorial’s sweeping lawns under a sombre winter sky, it was impossible not to weep.

Jack was one of two veterans who unveiled the plaque that day in front of assembled dignitaries including the Chief of the Australian Defence Force. I sat with him on the stage before the ceremony and held his hand in the biting Canberra cold.

‘How are you feeling?’ I asked.

‘Good,’ he replied. ‘No worries. I’ll be fine.’

And he was. Back ramrod straight, he played his part to perfection. Afterwards he whispered to me quietly: ‘It was the best day of my life.’

As well as producing ongoing friendships with veterans and their families, the day yielded an unexpected sequel. Not long after, a literary agent got in touch. She had seen Jack and me on TV during the numerous interviews we had done together and wondered whether I might like to write a book for a popular audience on Jack’s WWII Borneo operation: Operation Semut. It was a breathtaking suggestion. I had been collecting material for a book on WWII in Borneo. But as an academic anthropologist, the book I’d planned was very different from the one dangled before me.

I spoke to Jack. ‘There’s never been a detailed book written about the whole of Semut,’ he said wistfully. But I had no need for that gentle prod. Within a day I had decided. And so I, unlikeliest of military historians – an anti-war activist for much of my life – found myself writing a book about a secret military operation in the heart of Borneo.

Much has happened in the ensuing four and a half years. I began collecting archival and personal material for the book, interviewing the remaining operatives, talking to operatives’ families, and revisiting the many interviews I had conducted in Borneo about the war. Jack and I developed a habit of speaking on the phone every Sunday afternoon: a weekly pause for laughter and shared confidences. I visited him in Adelaide in October 2016, staying in his little house in the suburbs where he cooked me porridge for breakfast and his daughter Lynnette brought us comforting evening meals. We pottered around in his garden, watched AFL on television and drank countless cups of tea. But mostly we talked about the war, Jack working back through his prodigious, remarkably accurate memories.

In the meantime I co-curated an exhibition at the Australian War Memorial on Australian WWII special operations in Borneo. Four of the five surviving operatives from those operations, including Jack, made it to Canberra for the opening in April 2018: all now looking unbearably frail. Jack and I slogged through more media rounds. But 2018 was a bitter year. In May my life partner Barry Hindess died. In July Jack followed him. I travelled back to Borneo a month later, nursing my sense of loss as I trekked to longhouses and communities, following in the footsteps of Jack and his comrades more than seventy years earlier.

And curiously, in the grip of profound grief, the story of Operation Semut sustained me. The hardships and joys experienced by its men became my own; I dreamed about them at night and sweated with them during the intensely humid days. Gradually, the book turned into two as I realised the operation was too large and sprawling to be confined within the pages of a single volume. My publisher kindly granted me extra time to get it finished.

Jack gave me carte blanche to write about the operation exactly as it happened, joking on several occasions: ‘There’s nothing they can do to me now.’ So I have scrupulously set down the truth while, at the same time, trying to do him and his fellow operatives justice through the use of additional material to contextualise their experiences. His only stipulation was that the role of Borneo’s indigenous Dayak peoples should be properly acknowledged: ‘You have to tell them how important the Dayaks were.’ This accorded with my own instincts as a student of Dayak peoples, and I have done what he asked. I hope the result would have made him proud.

NOTE ON Z SPECIAL UNIT AND SRD

The organisation to which Jack belonged – which he called Z Special Unit – had the formal name Special Operations Australia (hereafter SOA). SOA took the cover name Services Reconnaissance Department (hereafter SRD), and this latter name is the one by which it is more commonly known. Australian Army personnel who joined SRD – the majority of those in the organisation – were posted to and administered by Z Special Unit, and this was the name usually recorded on their service records, secrecy declarations and discharge papers. This name was also recorded on the documents of many other SRD personnel, even those who had not joined from the Australian Army.

As a result, Z Special Unit was the only name many SRD recruits knew for the unit they served with, some not discovering until long after the war that the larger SRD organisation existed. Many saw themselves, both during and after the war, simply as members of Z Special Unit.

SRD is the name I generally use for the organisation throughout this book. I use the terms Z Special Unit and SOA only when the particular context requires it.

NOTE ON SOURCES, ORTHOGRAPHY, LANGUAGE AND ABBREVIATIONS

Had I realised in advance how challenging it would be to write an accurate history of Operation Semut I might not have started – and so would have missed the experience of a lifetime. The project’s difficulties have been due not least to the absence of detailed military accounts of the operation from the time. Most SRD files appear to have been destroyed at the end of the war, and those remaining were culled by official agencies in the following years. Similarly, personnel files for individuals who served with SRD are often missing from both the Australian and British archives. The unpublished history of SOA, produced after the war by the body’s official historian, is partisan and, with reference to Operation Semut at least, full of inaccuracies – partly because it uncritically accepts information provided in operational reports that were themselves often incorrect. Unit war diaries were not kept for SRD, as they were for many other military units. And even when official accounts are available, details can vary markedly from report to report. As a result, I have struggled to pin down dates, places, personnel and even what happened for any particular event.

This means I have been heavily reliant at times on personal accounts, from both operatives and local peoples. Not only has it been difficult to locate such accounts – almost all of them are unpublished – but they are also notoriously inaccurate. All of the operatives were required to sign secrecy provisions when they were recruited to SRD; as a result, many did not begin recording their experiences until long after the war. Like the official reports, these accounts have had to be handled with great care.

To complicate matters further, both official and unofficial accounts from the operative side are full of mistakes with respect to local names (of both people and places) and local detail, including locations and distances. Sometimes it has taken weeks of sustained research to accurately identify a longhouse the operatives visited, a river where an important action took place, or a local leader they met. In this I was often reliant on local Borneo memories – as well as the fieldnotes of an older generation of anthropologists and the always invaluable Sarawak Gazette.

The arrival of COVID-19 on the world stage in early 2020, and subsequent closure of archives in Australia and the UK, created additional complexity. From this time it became impossible to access certain crucial documents. As a result I was required, very late in the piece, to reshape elements of the book.

But the research’s rewards have far outweighed its tribulations. I have spent a great deal of time poking around archives, including the Australian War Memorial, the National Archives of Australia, the National Archives (UK), the Imperial War Museum (UK) and the Australian Special Air Service Regiment Historical Archives. A number of very generous individuals also allowed me to dig through their private collections of papers.

As well as foraging in both official and unofficial written records, I have fossicked in oral ones. In 2015 and 2018 I travelled throughout the northwestern part of the island of Borneo (the Malaysian state of Sarawak), largely to the areas where Semut had operated, and recorded – the majority of them on video-camera – around one hundred and twenty lengthy interviews with locals, mostly Dayaks who were alive during the war. I also interviewed – several of them a number of times – most of the surviving SRD operatives who had been on WWII operations in Borneo, including all three who had taken part in Operation Semut. I was lucky enough to have additional casual telephone conversations with two of these Semut operatives (Jack Tredrea and Bob Long), during which Operation Semut was often discussed. The information gained from these encounters was key to filling many of the gaps in the Semut record.Perhaps most importantly, since 1985 I have had the privilege of conducting years of ethnographic fieldwork in Borneo: from this I have learned a great deal about its peoples – especially its Dayak peoples – and places. During this time I have taken part, using local languages as much as possible, in hundreds of informal conversations with Dayaks – and others – about WWII. This has provided the ballast for my account.

The Borneo fieldwork and interviews presented their own suite of difficulties. Travelling throughout remote Borneo even today can be gruelling, which possibly accounts for the note of sympathy the reader may detect when I describe operatives’ 1945 jungle journeys. Many Dayaks are highly mobile; entire communities will up sticks and move to a new place for a variety of reasons. On two occasions I went to considerable effort to reach remote communities mentioned in operatives’ accounts, only to discover that the people who were now there were not the same as those who had been there seventy years earlier. In addition, I was required to work across a large number of different Dayak languages, which entailed its own logistical challenges.

Since this book is intended for a general readership rather than an academic one, I have not provided exhaustive footnotes. Rather I have detailed sources of quotations and other key information in endnotes at the ends of paragraphs.

Unless stated otherwise I have used modern spellings throughout – these are generally much closer to the local terms than the largely Europeanised spellings of 1945. For example, the Rajang River of the 1945 accounts is spelled Rejang River here. In the original accounts it is not uncommon to have three or four spellings for one place or person – e.g. Long Beruang on the Tutoh River is variously spelled Long Bruang, Long Beruang, Long Berawan and Long Briang. Again, unless indicated otherwise, I have reduced them all to one common spelling: the one conventional in 2021 when this book was finalised. Similarly, many of the old accounts spell Dayak as ‘Dyak’, and some readers may be familiar with that spelling. However, it is now considered archaic, and I have spelled it as ‘Dayak’ throughout, except in direct quotes.

As an anthropologist, I have wanted to convey something of the lifeworlds of those who took part in Operation Semut, and to that end have included many direct quotes from participants in the text. Readers should be aware that, as a result, they may be confronted with terms acceptable to an earlier generation – such as ‘boys’ for Borneo locals and ‘Jap’ or ‘Nip’ for Japanese – that many now consider inappropriate or disrespectful.

One of the most difficult aspects of writing this book has been getting on top of the multitude of acronyms afflicting military literature. I have tried to protect my readers from this disease, and have used acronyms as little as possible. However, some were unavoidable; they are mostly found in Chapter 3, on operational planning. They are given below.

AIF Australian Imperial Force

BBCAU British Borneo Civil Affairs Unit

HQ headquarters

LMG light machine gun

OR other ranks

POW prisoner of war

SOA Special Operations Australia

SOE Special Operations Executive

SRD Services Reconnaissance Department

SWPA South-West Pacific Area

WWII World War Two

Christine Helliwell

February 2021

Semut Christine Helliwell

Winner of the Les Carlyon Literary Prize and the Prime Minister’s Literary Awards Australian History Prize. First Runner Up for Templer Medal Book Prize (UK). Shortlisted for the NSW Premier's Australian History Prize, the ACT Notable Book Awards, and the Reid Prize. A remarkable new book about Operation Semut, an Australian secret military operation launched by the organisation popularly known as Z Special Unit in the final months of WWII.

Buy now