- Published: 28 September 2021

- ISBN: 9780143795780

- Imprint: Penguin

- Format: Paperback

- Pages: 336

- RRP: $26.99

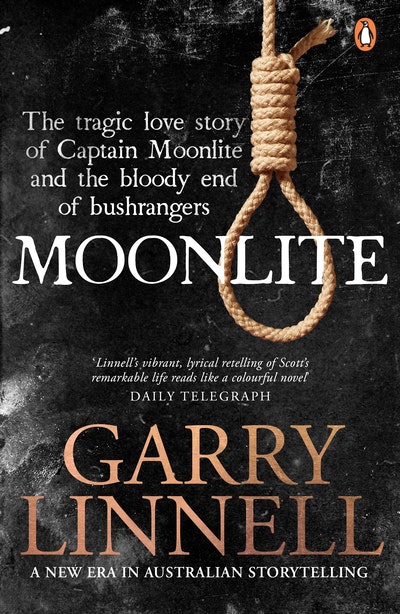

Moonlite

The Tragic Love Story of Captain Moonlite and the Bloody End of the Bushrangers

Extract

Bob can’t have that. Too many people – important people, like the politicians and prison officials who keep him in his job – are counting on him to get this right. A mistake on the gallows in front of dozens of them tomorrow morning – the knot incorrectly placed behind the left ear, or the drop and the weight of the condemned man poorly misjudged – would be . . . unfortunate.

It would lead to even more criticism and assaults on his professionalism and character.

Bob is no stranger to the slights and cruel barbs of his fellow man. Is there a job in the world that carries more stigma than the role of state executioner? Bob likes a drink. That is true. In the days leading up to an execution nerves will sometimes get the better of him. Locals will often spy him clutching a lamppost for support after downing one too many. He’s a big man with an even bigger appetite. But many pubs will no longer serve him a beer, and those that do often smash his used glass so it will not taint the lips of other drinkers.

Why, he still burns with the memory of that night not so many years ago when the Sheriff, Mr Charles Cowper, invited Bob into his home to help his wife prepare a dinner party. Bob had never been one to turn down an opportunity to earn a few more quid. He took on the role with his usual gusto and enthusiasm. He polished the silverware. Helped the cooks in the kitchen. Made sure the place was spotless. But when the guests learned the executioner’s death-stained fingerprints were all over their cutlery, they rose together and angrily demanded he be removed. An embarrassed Mr Cowper was forced to ask him to leave.

A man needed a thick skin to persist in such a vocation. No point becoming bitter whenever you walked into a room and all conversation stopped, or good folk saw you coming down the street and quickly crossed to the other side.

Who could blame them? They all read the newspapers, which had been hurling insults Bob’s way for years. But few, surely, had been as cruel as those that appeared in print just a few months earlier when Bob presided over the hanging of a young man in a small country town.

Journalists are a bloodthirsty mob eager to entertain their audiences with the most grotesque details of a man swinging from a rope. But being the good bloodhounds they are, they have caught a whiff of change in public sentiment and are campaigning fiercely. Whipped into a frenzy of righteous indignation by preachers and other do-gooders, polite society has now determined that capital punishment for anything less than murder is a crime before God, the act of an uncivilised nation.

In Sydney, thousands had taken to the streets, walking solemnly in time to the beat of Handel’s ‘Dead March’ on muffled drums. They had signed petitions and gathered in growing fury to oppose the impending execution of Alfred, an Aboriginal man convicted on flimsy evidence of the rape of a 60-year-old woman. While the crowds prayed and lit candles and called on the Governor of New South Wales to show compassion, Bob had taken a train and then a Cobb & Co coach to Mudgee to carry out the government’s orders and oversee the hasty erection of the gallows.

He arrived to discover a town on edge. The governor of the local gaol was racked by guilt over the impending hanging and was drowning his self-loathing in whiskey. The local carpenters had no experience putting together a scaffold and Bob had to pay attention to every little detail, overseeing the placement of every beam and nail. Sandbags weighing roughly the same as Alfred had to be stitched together so the execution could be rehearsed and the drop for the body accurately measured.

A reporter for one newspaper opposing the hanging stole the rope that Bob’s assistant had brought from Sydney. A new one had to be quickly found, stretched and soaped.

On a bitterly cold morning just after nine o’clock, Bob and his assistant had escorted Alfred to the gallows. Despite all the obstacles and setbacks, the hanging went smoothly. Alfred, baptised hastily overnight as a Christian, had been dispatched to his new God with a minimum of fuss. Bob could once again take pride in his work.

But back in Sydney there was no respite from the attacks on his character. One newspaper gave its readers a long and brutal assessment of the execution. ‘The wretched blackfellow was borne along between the frowsy executioners, who gripped his arms as though they liked their work of blood,’ it reported.

Frowsy? Many readers would have had to put down their evening shandy and reach for their dictionary to discover that Bob and his assistant looked scruffy and unkempt, sloppy and dishevelled, badly dressed and dowdy . . .

And then came this: ‘The hangman, 6ft. 2in. in height, broad shouldered, spider-legged, with arms like a gorilla, a flat face without a nose, and huge feet, presented a spectacle to be seen nowhere else out of Hades.’

There it was. Again. That flat face without a nose. The reporters never missed an opportunity to highlight his ruined features. ‘Our hangman is a ghoul,’ began a typical report. ‘He is known as “Nosey Bob”, a soubriquet earned through a disfigurement of his face. He was kicked by a horse and his nose so badly smashed as to almost obliterate all semblance of even a snout.’

Nosey Bob. The man with a gaping hole in his face. The accident had occurred years earlier, back when he was a coachman, ferrying the well-off around the streets of Sydney. He’d been a good-looking man back then, a tall, strapping fellow who could secure a second glance from even the most chaste of women. Well known, too. When the Duke of Edinburgh, Prince Alfred, had toured the colonies in the 1860s, Robert Howard had been his preferred Sydney guide, steering his royal highness through Sydney’s darkened streets and toward its best brothels.

But one kick from that damn horse. It had changed everything.

Songs and poems had been crafted and dedicated to Nosey Bob. One had been published to much acclaim in one of the newspapers about his journey to Mudgee for Alfred’s hanging:

The river gleams like a crystal floor

Where the track meanders beside its shore,

And, reflected upon its mirrory bed,

Goes the shade of the hangman’s noseless head.

People would laugh, children would stare and all would sneer whenever he left his cottage and made his way to work at Darlinghurst Gaol. The injury had cost him his job as a coachman, because few of his regular clientele felt comfortable with a noseless driver holding the reins. He had doused his bitterness in grog for a while until the job of hangman was offered to him. It was a profession few others wanted to pursue. Everyone knew it had sent a previous incumbent tumbling toward insanity and life in an asylum.

Worse, some thought Bob’s position as executioner, coupled with the constant taunts about his mutilated face, had brought about the premature death of his wife. Jane Howard had been 42 when she died. She had been the only person in his life who had stood by him, who understood him, who saw the gentle man behind the ugliness, who unquestioningly loved him and had given him three beautiful daughters and two sons.

Without Jane, who passed away two years ago, his life has become so much bleaker. And so he has retreated as much as he can from public view, hiding out in his tidy cottage in Sydney’s east, caring for his children and worrying about that rope.

The executioner continues pacing the floor. Tendrils of pipe smoke curl upward, past that noseless face. A beer would be good to settle the nerves and wet the lips. Working with death can dry out a man. His guts might heave when an execution nears and those stares from passers-by might become more intense. But Bob’s outer skin is now a hardened shield protecting him from all the bile and disgust flung his way. He will need it more than ever in these next few months. One of his cherished daughters will pass away. Death surrounds him. There is no end to it.

The only way to cope is to stare it down. To intimidate it. So he plays up to his reputation for eccentricity. If the newspapers want to cast him as an unflinching ghoul, a macabre figure with a gruesome appetite for death, then he will give them what they want.

‘Prisoners are treated too kindly and kept too long,’ he will tell one reporter. ‘They get flabby. The muscles of the neck soften, and the neck gets as tender as a chicken. No man should be kept longer than a week or a fortnight if you want good work and a first-class execution.’

This is the Nosey Bob they expect, the man whose mission in life is to snuff out the light in other men’s eyes with a well-greased rope and an oiled trapdoor ready to send them plummeting directly to hell.

He will not give them the man Jane knew – plain old Bob, the tender and devoted husband and father, the man who took on a job no-one else wanted because he had to provide for his family, the man who arrived home one Saturday night, face flushed with embarrassment and shame after being forced to leave the Sheriff’s home by the back door, all because his fingers had touched the damn silverware . . .

No. They will never know the real Bob. No subtleties, no halfmeasures. Soon he will leave the city and move to a small cottage out near a sandy cliff at North Bondi. Visitors will find sets of shark jaws in his front yard, bleached by the sun and scattered on a soft bed of pine needles shed by two overhanging trees. Bob likes fishing. But he is not one for intricate lures. Not for him the delicate patience required to catch cautious snapper or skittish whiting. He will prefer one large barb forced through a chunk of fresh meat and hurled into the ocean. Then he will wait for the line to go tight and wade into the sea, pulling in the hooked shark until it is so close he can tie a rope around its tail and drag it on to the sand. ‘When I hook a particularly big chap,’ he will recall years later, ‘. . . a fellow that is too big for me single-handed, I make fast the line and get the old horse to pull him out.’

Quite often there will be a sound outside that cottage on the hill, a snort in the growing darkness. He will know it well. That old horse will pull up at the front gate and wait patiently for its master. They won’t see Nosey Bob very often at his local pub, the Cliff House Hotel down in Campbell Parade. Best to avoid the stares and insults and occasional invitations to fight. Instead, he will train the horse to walk down to the pub with a tin can strapped to its side and the right amount of coin in a satchel. The publican will fill the can with beer and the horse will amble home slowly, no sway in its hindquarters, just the way Bob likes it.

The executioner will then wander outside, collect his pail of beer – not a drop spilled, either – and go back inside to slake his thirst and think about all the things that can go wrong with a simple length of hessian rope.

Just like tonight. The clock ticks. Thomas Gainsborough’s ‘Blue Boy’ stares at him from one of the walls, unblinking, all-knowing. Tomorrow the whole town will be waiting and watching. It will be a rare day, a moment to savour and perhaps even cherish. For once the entire city will be behind him.

On this mild evening in Sydney there are no passionate demonstrations in the streets, no candlelight vigils outside the Governor’s residence, no powerful editorials in the newspapers berating the government for sending another man to the gallows at the hands of a noseless, frowsy executioner. A handful of preachers might be muttering from their pulpits about the brutality of condemning a man to death, but surely that is for appearances only.

No, this time the whole town is baying for blood and praying that Nosey Bob gets the job done. They want this bloody era of outlaws to end. They want the deep, dirty convict stain that has blemished the colonies of Australia for a century to be scrubbed clean.

Most of all, they want to know that Captain Moonlite has been hanged by the neck until he is dead.

Moonlite Garry Linnell

From Walkley Award-winning writer Gary Linell comes the true and epic story of George Scott, an Irish-born preacher who becomes, along with Ned Kelly, one of the nation’s most notorious and celebrated criminals.

Buy now