- Published: 17 July 2017

- ISBN: 9780143770602

- Imprint: Penguin eBooks

- Format: EBook

- Pages: 288

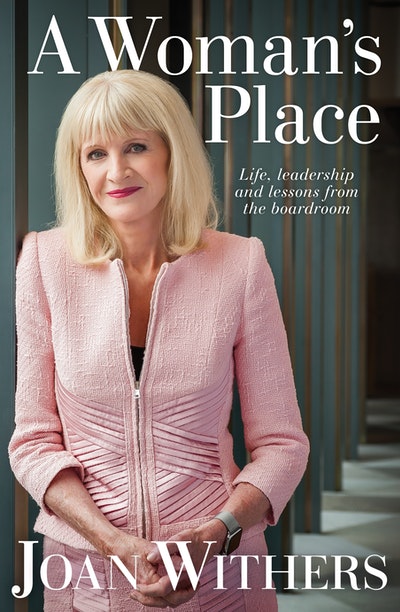

A Woman's Place

Life, leadership and lessons from the boardroom

Extract

My childhood wasn’t privileged or advantaged in any way. My parents, John (Jack) and Lilian Blinkhorn, were a working-class, Catholic couple from Manchester in the north of England. They arrived in New Zealand on a Dutch immigrant boat in 1959 with their three daughters in tow: my sisters Mary and Anne, and me. I’m the middle (and definitely the most rebellious) daughter; Mary, who was born in 1948, is nearly five years older than me and Anne (born in 1957) is four years younger.

The trigger for the move to New Zealand was the death of my maternal grandmother. She died of an aneurysm in March 1959, the year we left England. She had lived with my family from the time I was born, on 6 August 1953. My mother was devastated by her death.

My father’s parents were already in New Zealand so, about three months after my grandmother died, my mother and father decided to emigrate. That five-week (but certainly not five-star) boat trip is one of my first childhood memories.

I remember getting off the boat at Panama and seeing a black man for the first time; another memory is my father being refused service in a bank in that port for some reason I did not understand. The trip was very rough at times. The discomfort continued after we docked in Wellington where we were forced to then take a train to Auckland, plane tickets being regarded as too expensive.

On arriving in Auckland, we moved in with my paternal grandparents, whom my sisters and I were meeting for the first time. We girls had beds inside their Mangere East house but my parents slept in a caravan on the back lawn.

They were pretty horrendous times for us all. I remember going out to the caravan in the morning and finding my mother sobbing inconsolably because she was so homesick and grieving for her mother.

When I arrived here one of my biggest aims — in fact, it was a driving urge — was to lose my northern English accent. I sounded so different to the other children and it made me stand out. I wanted it gone. I worked really hard and focused on saying words the way they were spoken here. There wasn’t any bullying or bad treatment at school because of it — I simply didn’t want to sound different to everyone else (though I can still do a very good impersonation of a northern English accent).

In the classroom, in particular, I was so conscious of it. To me, it sounded very down-market. At that stage we didn’t have a television set but from the limited exposure I’d had to American accents, I thought they sounded cool and sophisticated.

I didn’t talk to my parents about it but they must have noticed. On the rare occasions we had phone calls with my aunty in England, she would say we sounded like Kiwis. Mum and Dad never lost their accents, though over time their voices mellowed.

Mary eventually managed to sound like a Kiwi but it took her much longer than it did me. She was 10 when we arrived and I’ve never been able to work out whether it’s harder when you’re older or whether she didn’t feel the same imperative to do it.

Almost as soon as he arrived in Auckland, Dad started work at Reidrubber in Penrose, doing shift work and putting in 60 hours a week coiling hoses. He worked there, in a filthy factory, until the mid-1980s when he retired. Two of my uncles worked at Reidrubber and my grandmother had a job in the office there too.

My father was highly intelligent and even now, when I’m facing big workloads and feel times are tough, I think nothing could compare to what he had to endure.

My strong work ethic comes from my father. Throughout my career, the ability to work hard has been one of my key strengths. If it means getting up at 3am, I’ll do it so I’m always prepared and have thought through the issues facing me during the day ahead. Dad worked every hour God sent to support his family. He was very warm and loving with a great personality, but he wasn’t a man’s man. Not that he was in any way effeminate but he was a bit of a mummy’s boy and had no interests outside the home. He was also extremely frugal. In fact, my father was so tight he kept a notebook to record everything he spent, including tiny amounts for things like lollies for us girls. When Mary and I were teenagers, he bought an Austin A30 as the family car. We would all be taken to Mass on a Sunday in this vehicle, which was clearly not designed for a family of two adults and three growing girls.

I’ve always thought Dad was the perfect man — if you want to be married to a saint. He adored my mother and I’d stake my life on the fact that he was never unfaithful to her.

Dad spent a big chunk of his early working life serving in the military, so he didn’t receive the education he needed to reach his full potential. He joined the territorials in 1935, at the age of 15. (Dad’s father lied about his age so Dad could get some training as his father could see World War II was imminent.) So from then until he was demobbed in 1946, my father was involved in the army, including serving overseas. This meant his education was truncated, so after the war he went into sheet-metalworking and did an apprenticeship.

Soon after, he met my mother, who was a registered nurse. She had nursed during the war. I think my father was absolutely besotted with her but I’m not sure my mother was quite as enthralled with him. There was an interesting emotional dynamic between the two of them but they ended up staying together until they died at a ripe old age, Mum on 19 September 2010 at almost 90 and Dad on 11 December 2012 aged 92.

My relationship with my mother was difficult and complex.

She didn’t work outside the home in England when I was small, although she had worked as Matron of a day nursery when Mary was little. After we came to New Zealand we were so hard up that she had to work throughout most of my childhood — something I hated, which is pretty hypocritical given the route my life has taken. In New Zealand her first job was as the Matron at the Motherhood of Man day nursery in Owairaka, and then she worked in a senior position at the same organisation’s home for unmarried mothers in Grey Lynn. We lived in a flat above the day nursery, a beautiful two-storey building that was the nicest home we had during my childhood. It is still there today. My son Jamie and his partner Margaret Douglas once lived in a property nearby and I’d often push a pram past that building when my granddaughter Indiana-Rose (Indie) was a baby.

When I was growing up, my mother was the most demanding personality in the house. Dad would do anything for her. She’d snap her fingers and that was it — she’d get her own way. I think it was Mum’s innate personality, rather than her nursing training, that made her that way. She didn’t care what effect she had on people and she had no sensitivity to their reaction. I haven’t inherited that gene — I can’t stand being out of sorts with people I care for. In her defence, she lost three siblings when she was a child, two as infants to scarlet fever within a week of each other.

I remember she would come home from work every night and drink a big bottle of beer. She’d sit in the lounge in front of the television, and drink and chain-smoke — a habit she’d taken up during the war. My mother was such a heavy smoker that Dad had to paint the ceiling in the lounge once a year. The area above her chair had become so discoloured that the first stroke of white paint would make the rest of the ceiling look Karitane yellow. However, she wasn’t hugely affected by smoking until the last year of her life, when she was almost 90. Then it really took its toll and she died of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease.

My mother wasn’t demonstrative when it came to showing my sisters and me any physical affection. We’d get a peck on the cheek at bedtime and that was largely the extent of it. Dad was very affectionate, and would cuddle us and carry us on his shoulders when we were little kids.

After Mary, my elder sister, was born, I’m told my mother had a nervous breakdown and didn’t speak to my father for months. She suffered some form of post-natal depression. To make it worse, her own father, who had been gassed while serving in World War I, died while she was pregnant with Mary.

She simply wasn’t good at establishing trust or confidence with me while I was growing up and I quickly learned I had to be independent. On one occasion, when I was in Form 2 (now known as Year 8), I recall being really hurt when she promised to pay me $2 a week if I did jobs around the house. That money was quickly earmarked for buying clothes, magazines and make-up, and I was happy to do housework in the weekend to get them. I remember being devastated when she reneged on the deal, and refused to pay me, saying it was the sort of work I should be doing without compensation.

Fifty years later, this still rankles. I’m sure she would be horrified to know I’d carried that for so long but to me it was a total betrayal. I kept my part of the bargain and she just said no.

She was similarly hopeless — and this is not an understatement! — when it came to preparing me for puberty. It’s particularly difficult to understand this when you remember she was a state-registered nurse. I learned about menstruation from a girl at school, who had told me, ‘You know women bleed, don’t you?’ When I asked what she meant, she said, ‘Once a month, they bleed.’ But she didn’t tell me where they bled from. I took the bus to a dental appointment that afternoon and can remember sitting there, looking at other female passengers and thinking, ‘My God, they’re bleeding. Where are they bleeding from?’

When I got home, I told my sister Mary about this startling information. She spoke to my mother, who sat me down when she got home from work and gave me a five-minute rundown on sex and how it was absolutely filthy outside marriage. And that was it.

When it came to sanitary protection, she was just as bad. My mother reverted to her 1950s northern England roots, which involved ripping up towels, held in place with a sanitary belt. These were washed and hung out on the clothesline to dry. The whole situation was horrendous. I cannot understand why she didn’t seem to care.

Later on, a mother of one of my high-school girlfriends offered to help me deal with menstrual issues. There were a few people around who took pity on me — not that I needed pity — but they were people who understood that things were not being dealt with properly.

There were other issues. It was my Aunty Edna — not my mother — who bought me my first bra. Edna was a dressmaker who had worked in the theatre in London and was a fashionista of her day. She had dressed prima ballerina assoluta Dame Margot Fonteyn for Swan Lake, was beautifully groomed and I thought she was the most fabulous thing ever. She made my wedding dress and it was beautiful.

Edna came into our family via my father’s youngest sister Sophie, who married a merchant seaman called Tony. He was a Londoner through and through — a fabulous guy who was interested in jazz, and one of those adults who didn’t treat you like a child and actually asked your opinion. Edna was Tony’s mother.

When we were teenagers, my boyfriend Brian (now my husband) and I would sometimes drive to their house on Sunday afternoons and talk to them. I think Edna sensed the difficulty I was having with my mother, who was living, in my view anyway, a totally selfish existence.

When it came to clothes, Dad was more onto it than Mum and sometimes took me to a dressmaker to have things made. There were an awful lot of hand-me-downs, but it was worse for Anne than it was for me as she would usually end up being the third proud owner of any particular piece of apparel. Mum would knit cardigans — she was a fabulous knitter — and she knitted me a dress once but that was it.

I have never had a daughter (but I do have a granddaughter) and obviously I’m in different economic circumstances from my mother but even back in that era, I imagine a mother would take enormous delight in making that sort of stuff for her kids or buying things and seeing her kids enjoy them. To be fair, she did once buy me a pair of white Emma Peel boots (The Avengers was a popular television show in that era) and she scored a lot of brownie points for that. But those occasions were random and extremely infrequent. It was rare that she would surprise me with something positive.

Most of the time she was very critical. She also lied. I remember once we went on a day trip to Waiheke with a group called The British Kiwi Club. For some reason Mum wouldn’t let us take our togs, so of course when we got there we were asked why we weren’t going in to the water with all the other kids. In my inimitable fashion, I piped up and said ‘Because Mum wouldn’t let us bring our togs’. She vehemently denied the fact. In most instances, I think if it was more expedient to lie and get her own way, that is what she did.

And she was so ungrateful. My sisters and I laugh about this now but Dad was always beside himself with worry when it came to buying her birthday and Christmas presents. I remember one Christmas he bought her a relatively flash sun lounger from Farmers. He went to so much trouble but when he proudly wheeled it in, she said, ‘What do you think I am? An invalid?’ and totally dismissed it. She did mellow a little, though, as she got older.

I was more rebellious than my sisters. I would call my older sister ‘martyric’ — my derivation of an adjective from the noun ‘martyr’ — as she wouldn’t push the boundaries at all. I used to think, ‘Why don’t you rebel and fight back?’ Mary was absolutely compliant, and even as a teenager she displayed the selflessness and generosity that has been a lifelong characteristic. She did everything she was asked to do and more. For example, she would do all the family’s ironing on Sundays — a big job in those days. That wasn’t me! Anne has more of my genes — she’s out there, pushing the boundaries.

Mary had a much closer relationship with Mum and she still gets quite sentimental about her. Although, when the three of us get together, we talk about Mum and Mary acknowledges her foibles.

It wasn’t until after my son was born — on my twenty-first birthday — that my mother and I had any real connection. She adored Jamie because she’d never had a son and he was her first grandson. His birth wasn’t easy, and when he finally arrived the hospital staff told Brian he had to call his mother-in-law right away as she’d been on the phone every half-hour.

Even after Jamie’s arrival, you still could never win an argument with her — it was impossible. And it was another 17 years before my mother made the first positive remark she had ever made about me.

Jamie was in the seventh form at King’s College when he suffered a collapsed lung. I was at a Shirley Bassey concert with Kerry Smith, Radio i’s Breakfast host, and my car — an old Porsche 924 — broke down as we were leaving the carpark. I had a cellphone with me, one of the very early models, and tried ringing home. No answer.

This was about 10pm and it was highly unusual for nobody to be there. So I put Kerry in a taxi, called a tow truck and kept on ringing. I then remembered Jamie had a cold and was planning to go to the doctor. By this stage I was in the tow truck with the car on the back and very concerned about Jamie.

In fact I was so concerned that I rang Middlemore Hospital where I was told they couldn’t give me any information but his father was with him. It transpired that Jamie had gone to the doctor, where he was told he had pleurisy and a collapsed lung, and was admitted to hospital under some urgency. Ultimately he had to have his lung re-adhered to his chest — a surgery that needed to be done twice, as about a year later his lung collapsed again and he had to have the operation repeated.

It was midnight by the time I got home and Brian got back from Middlemore. The only person I wanted to speak to was my mother. I couldn’t call her at that hour so tossed and turned all night until 5am when I called her. By that point I was sobbing. She said, ‘You don’t deserve that. You’ve treated him like gold.’ It was the only really positive thing I can remember her saying to me in my entire life.

Sadly she reverted to type when my father started showing signs of Alzheimer’s disease in his old age. She refused to accept he was really sick.

Dad had developed bowel cancer in 1970 when he was in his late forties. His father had died of the disease that same year so Dad was acutely aware of the symptoms and went to his doctor for tests. These came back negative but the doctor was convinced something was wrong and sent him back for further evaluation. They found the cancer in its very early stages and my father made a complete recovery.

Dad became ill again many years later when he and my mother were living in Selwyn Oaks, a retirement village and rest-home complex in Papakura. Just before Christmas 2008, he started coughing up something that looked like coffee grounds — the problem turned out to be adhesions which were related to the original bowel-cancer surgery. He needed another operation.

Dad had also become a bit forgetful and there was a significant deterioration after his surgery. He nearly died post-operatively — in fact, he was given the Last Rites. On Christmas Day everyone went up to the hospital to visit him. Mum was in fine form — she accused him of over-acting! Anne had given up most of her Christmas Day, the first following the birth of her first grandchild, to be with Dad. Mum was particularly critical of her indulgence of him.

When he was well enough to go back to Selwyn Oaks, Mum refused to sit at the dinner table with him, saying he was ‘doo-lally’. Once he became not fit-for-purpose, she seemed to think he was expendable.

In spite of this, it was my mother who died first.

We laid her out in the dress she’d worn to my wedding. She loved that dress, also made by Aunty Edna. On her first visit back to the UK and Europe the year before I was married she had seen a similar design and described it to Edna. She’d always said she wanted to be buried in it though she was much bigger by that stage so they had to shoehorn her in.

I’m not sure that Dad realised exactly what was going on. When my sister Anne wheeled him in to see my mother, laid out in an open coffin, he said, ‘That’s so sad. Who is she again?’

We cracked up laughing. In spite of his illness, he never lost his innate charm and politeness but everything else had gone. For a long time he managed by calling everyone ‘love’. He knew he should know us but he didn’t remember our names. And now he didn’t recognise the woman he’d been married to for 60 years.

I met my husband Brian at a dance at the Papatoetoe Rugby Club Hall. Churches in those days were good at organising that sort of activity and there was always a dance on a Friday, Saturday or Sunday night.

Brian was 17 and an apprentice electrician; I was 15 and in my School Certificate year (Year 11) at McAuley High, a Catholic girls’ school in Otahuhu.

My family moved house several times since those first few months with my grandparents at Chaplin Street, in Mangere East. From Mangere we moved to the flat above the day nursery in Owairaka, and from there we went to Cricket Avenue, where the Eden Park grandstand was later built.

For the next few years we rented the Cricket Avenue property from two wealthy ladies, Miss Furley and Mrs Sweetapple, who lived together in a beautiful house in George Street near the Auckland Museum. They obviously felt sorry for us because they would bring us boxes of food that was past its expiry date. We weren’t impoverished because there were two incomes coming in but my parents were committed to owning a house and were furiously saving for the deposit.

I still think fondly about Cricket Avenue as there was a grandstand in the back yard. Miss Furley and Mrs Sweetapple had a returned serviceman friend who had burst his bladder in Eden Park because he couldn’t find a toilet, so they built a big wooden stand in the back garden so they could invite friends to watch rugby and track and field events. Even in those days Eden Park was a sought-after venue, hosting athletes like Peter Snell and Murray Halberg.

I remember picking lemons off the trees in the garden and selling them to visitors to the stand. I can’t recall how much I charged but I had a sign that had a price per pound but no scales, so I was selling them by the dozen.

In 1964 we bought a brand-new group house at 161 Methuen Road in Avondale. It’s still there but it looks very different today! Back then it was a typical new group-housing subdivision, with loads of young families in the area. It was a lot of fun for us kids and I recall we made a substantial hut underneath the Nuttalls’ place further up the road. Most of the houses had garages underneath and the adjacent excavated area was a source of great adventure. I can remember lots of trees and using them to swing across the creeks like Tarzan. When I think about it now, I’d be horrified if my grandchildren were out there doing something like that!

We’d disappear all day. Mum was working so Mary was frequently in loco parentis. I can’t remember her being particularly restrictive so we had a lot of freedom to spend time outdoors. At one point I think Mum had a couple of years off because I remember her cooking dinner and making apple pies, but for most of our childhood she worked. Otherwise, at Methuen Road it was the same dinner every night — three slices of luncheon sausage and a tomato. My job was to cross the creek to Hendon Avenue in Mt Albert to get the luncheon sausage and tomatoes because Mary was looking after Anne.

We shifted to Papatoetoe in March 1966. Suddenly my parents sold the Methuen Road house and we were again on the move. I am not sure what drove the shift — maybe their mortgage was too big — but, unbelievably, we found ourselves living with my aunty and uncle in a two-bedroom house on Puhinui Road. My aunty and uncle were building a unit out the back to live in but it wasn’t complete when we first moved in.

Three girls and two parents in a two-bedroom house! It was cramped and inconvenient but Mum and Dad lived there for years and we three girls were there until each of us got married. The dining room was turned into a bedroom for Mary, so she slept in the space between the kitchen and the lounge. It was altogether a very strange move but, if we hadn’t shifted to Papatoetoe, I’d never have met Brian.

Our schooling was all at convents and I think I received a good education. Initially I started school in Denton, Manchester, and then after arriving in New Zealand we went to Saint Joseph’s in Otahuhu, then to Christ the King on Richardson Road, Owairaka, near where the Maiora Street onramp is now. It was a long walk in the cold weather from Methuen Road but I enjoyed school. The nuns were strict but not unreasonably so, and I can’t remember any major falling out with the teachers. I particularly loved reading. I didn’t find school difficult, received good reports and generally did pretty well. I never got distracted until I met Brian.

Otherwise, it was a very ordinary existence. Ensconced at McAuley High School, I dropped maths in Form 4 — I’m not sure why — and for School Certificate I took English (achieving 92 per cent), French, geography, history and biology.

McAuley was a good school headed by a nun from the Sisters of Mercy order, Sister Margaret Mary, who later changed her name to Sister Moira Feeney. I made lifelong friends at the all-girls school, and even though we don’t see each other frequently, a recent 50-year class reunion proved that the camaraderie is still strong.