- Published: 18 August 2020

- ISBN: 9781760899134

- Imprint: Penguin

- Format: Paperback

- Pages: 288

- RRP: $26.99

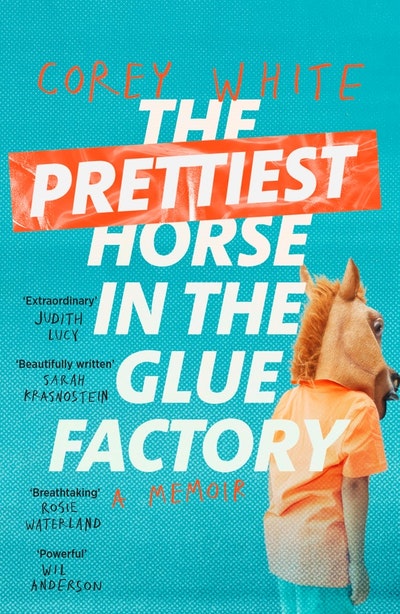

The Prettiest Horse in the Glue Factory

A Memoir

Extract

One night after we have killed cane toads, we lie out on the dewy grass, looking up at the stars.

My father drinks a beer and smokes as I lie on his chest, feeling safe.

‘How many stars are there?’ I ask.

‘Nobody knows. Pretty cool, hey?’

I nod, bewildered.

‘Heaven’s up there too,’ he says, cigarette wagging in his mouth. ‘If you’re good, you’ll go there.’

I smell the cane toad guts on my fingers. ‘Do cane toads go to Heaven, Dad?’

He pauses. ‘If they ask Jesus to forgive their sins.’

My father mentions sin a lot. I am five and I don’t quite understand what it is. It seems very grown-up and important, like tax or America.

‘What’s sin?’ I ask yet again, feeling as incapable as when I try to say hospital properly.

‘Sin is doing what goes against God’s wishes.’ Out of the corner of my eye, the little sun of my father’s cigarette glows. ‘Drinking like Daddy is. Smoking like Daddy is. Every person sins, but Jesus died for us so we could be forgiven and have eternal life.’

I savour the enormity of his pronouncement.

Then I feel clever. ‘What if you don’t have any sins?’

‘You’re innocent now,’ he tells me, ‘but one day you’ll sin.’

That’s one of my few early memories. I forget more than I remember and what I do remember are shredded vignettes, bad student films, as if I were born with a reverse dementia which gradually lifted. Things before are a muddled chronology. A great veil cloaks the years.

I lie in the dark counting the letters. Sin. S-I-N. Three letters. Three. 3. Sin, sin, sin. I like that it is symmetrical, you can take the s and put it on one side then while the i is in the middle you can give half of it to the s and half to the n.

I think I am four when I first realise that I am alive. I am hiding in a bush in our front yard, playing with Matchbox cars in the fine grey dirt. I watch a man walk his dog on the footpath. The dog, intrigued by something, cuts across his owner’s path then darts behind his legs and back in front, binding then toppling him. ‘Shit!’ yelps the man as he falls face-first onto the concrete. I giggle, enchanted by the misfortune.

We live in a Housing Commission estate in Caboolture, a pale brick house in a long street of pale brick houses with fences of tessellated wire diamonds.

Cockroaches scatter over the pink kitchen bench, a vanishing constellation of brown bodies in the morning sun. I decide against Vegemite toast for breakfast. Instead I go to the fridge and take a good long swig of my mother’s Coke.

I can’t remember any of my birthdays. No, I can. McDonald’s. Pancakes. Too many to eat but I always got them. The little moon of butter that never disappeared.

___

My father bounces, in aqua shorts and no shirt, his skin warm caramel. Above the trampoline the world is lilac but for the orange sun, which is abandoning the sky, and we are floating and falling in unison. I love him, nothing is more delightful than being with him, I want to be closer to him than his moustache.

‘I don’t want to go to kindergarten,’ I announce, jumping hard to try to throw my father off-balance.

‘Give it a try, son.’

‘It’s shit.’

I love to jump. My mother tells me when I was three I leaped off the roof of a house and through the roof of a cubby house. Everyone raced to me, thinking I’d died, but I lay in the wreckage giggling. I’d been a very mischievous toddler. Apparently my parents had to tie me to my high chair to stop me from wandering off.

I believed these stories, these legends. Nothing could hurt me. I was invincible.

My father is wonderful at drawing; once he drew a tiger on a beer coaster with a biro and it looked like a photograph. I keep it in my pillowcase and admire it often. I hope one day I’ll be able to draw as well as him. He tells me I am destined for great things. He knew it before I was even a twinkle in my mother’s eye. When I build starships out of Lego he kneels down in awe and calls me genius. And because it is him telling me, I believe it completely.

___

I am a one-boy public relations operation for my father, shouting out press releases to anybody who will listen.

‘You know my dad jumped off the Townsville Bridge and lived,’ I shoot at Linda, one of my mother’s friends.

‘Wow!’

‘Nobody has ever jumped off the Townsville Bridge and lived except Dad.’

‘Gosh,’ she says, lighting a cigarette. ‘Do you know why he jumped?’

I’m stumped because that’s all the information I’ve been given to pass on.

I am not close to my sisters Belinda and Rebecca. To me they exist simply to reduce the amount of ice cream I get at dessert. And they are only my half-sisters; we have different fathers. Unlike mine, their faces are speckled with freckles which I think look like fly shit. I’ve never seen fly shit but I think that’s how it would look.

We fight a lot. For instance, my sister Belinda is always smelling her fingers for some reason and it makes me sick. I tell her how I feel about her finger-sniffing and she tells me it’s a free country. It’s embarrassing when we go shopping and she’s holding her hand to her nose like it’s a bouquet of roses.

Rebecca is stuck-up. She’s prettier than Belinda and knows it. She is good at school and dances and plays netball.

Jacinta is my real sister. My father is her father too. She’s four years younger than me – she’s only two. I don’t mind her.

I am my father’s favourite because I am his son. Rebecca and Belinda complain that I am my mother’s favourite too. I see no problem with this state of affairs. I am better than them. It seems only natural.

I play our Sega constantly. I want to be the greatest player in the world. The feeling of my mother and father watching me, yelping when I do something, makes my tummy feel like a smile. I sit in the lounge room until my mother forces me to turn it off for Neighbours and Home and Away.

‘Gimme a go,’ Belinda says, sitting down beside me.

‘No.’

She leans over and wrenches the controller from my hand. I punch her in the breast, the place I’ve learned is the best target. She slaps me in the face.

‘Dad!’ I yell. He appears. ‘Dad, Belinda stole the controller.’

He removes his belt and Belinda pleads that she is sorry.

‘Stand,’ he commands. She drops the controller in my lap and rises. ‘Come here.’ Belinda goes to him. He hugs her into his chest, locking his arm around the back of her neck. Then he brings the belt down on her backside, once, twice, three times. He keeps going. I lose count. She screams and screams until the screams become one scream. ‘Don’t,’ he puffs, ‘fuck with my son.’

I watch his arm release her neck and Belinda collapse to the floor gurgling, a broken water bubbler. He kicks her in the ribs and she groans. ‘Go to your room.’

Belinda crawls down the hallway, her crying fading like an ambulance siren.

‘Slut!’ I shout after her. My father pats my head.

‘Barry,’ slurs my mother from the couch. ‘That was too much.’

___

He hits my mother, he hits my sisters, but he does not hit me. I am special, his favourite. I am beloved.

My father takes me to the movies often. We sit in the cool darkness munching on popcorn and slurping frozen Coke. Once we go to see Casper the Friendly Ghost and I become obsessed. I put a sheet over my head and try to scare everyone. I’m unhappy that there are no white sheets in our house but I make do with pink.

‘Boooooooo!’

‘I know it’s you, Corey,’ Rebecca deadpans.

My little sister Jacinta, who is three, giggles like an idiot.

I’m upset they’re not scared so I sit on my bed and think. I realise for me to be a proper ghost I’m going to have to be dead.

I find my father on the couch watching TV. ‘Dad, I need you to kill me so I can be a ghost.’

‘Son, I can’t do that.’

‘Come on, Dad,’ I say, leaping on his lap, ‘I love you, please kill me.’

‘I’m not killing you, Corey.’

I kick away from him, furious. I decide when I grow up I want to die.

The Prettiest Horse in the Glue Factory Corey White

‘So beautifully written, so important, so absolutely unflinching as it gently takes you by the hand to show you exactly what the difference is between falling and flying.’ Sarah Krasnostein, author of The Trauma Cleaner

Buy now