- Published: 2 August 2022

- ISBN: 9781760898915

- Imprint: Ebury Australia

- Format: Trade Paperback

- Pages: 384

- RRP: $34.99

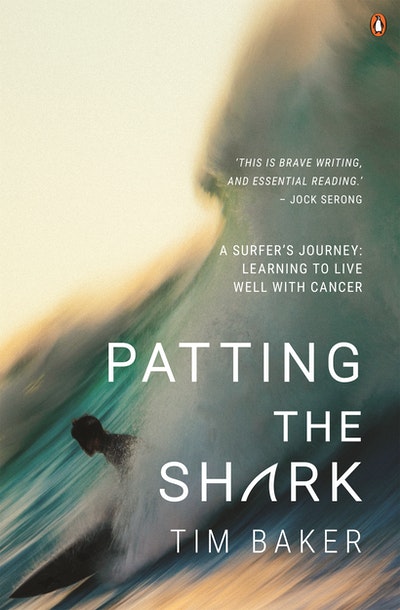

Patting the Shark

Extract

PUNCHING THE SHARK

A lone figure sits astride their surfboard, like a rider on a horse, calmly balanced, scanning the horizon, searching the vast blue undulations for telltale signs of an approaching swell. It’s a scene played out on thousands of beaches by countless surfers every day. But this particular scene is being witnessed by millions of viewers around the world, transfixed by a sporting contest about to transform into a mortal, human drama.

Suddenly, a boiling eruption of water, a flash of grey, the shocking appearance of a large dorsal fin so close to the surfer he can touch it. The surfer grips the rails of his surfboard like a rodeo rider, before he’s bumped off just as a passing wave obscures him from view.

We are left agonising over his fate for ten long seconds that feel like an eternity. When the wave passes, we see him swimming desperately towards the beach, before he stops, turns 180 degrees towards the horizon, treading water, as if deciding to face his attacker.

Some 11,000 kilometres away, I wake to the rowdy song of rainbow lorikeets in the golden winter morning glow of our Currumbin treehouse on the southern Gold Coast. Shafts of sunlight pierce the canopy of towering ironbarks. The radically altered nature of my reality gradually seeps through my semi-consciousness, like waking after a big night with ashtray brain and an empty wallet, times a thousand.

Old routines offer some small comfort. I make coffee, reach for my phone, check messages, socials, emails. It’s an odd way we choose to ease ourselves into the new day, the jolt of caffeine, the sensory onslaught of the world at our fingertips – every global disaster, every silly cat meme, every political scandal or disgraced celebrity, all mainlined through our own pocket-sized tower of babble.

But this morning is different. This morning there appears to be only one topic on everyone’s minds. And it does nothing to allay my own recently acquired case of acute existential dread.

‘Aussie Surf Star in Shark Attack,’ the headlines blare.

I’m wide awake. Mind racing. Who? Where? Brushes with mortality seem to be the theme de jour. The clip is everywhere across every conceivable digital platform, pro surfing finally cutting through to the mainstream but not in the way anyone would have wanted.

Soon enough my questions are answered. The who is my old mate, three-time world surfing champion Mick Fanning. The where is the notoriously sharky waters of Jeffreys Bay, South Africa. Six years earlier, I’d been holed up in a spare room of Mick’s luxurious beachfront rental at that very spot. Mick had been bundled out of the event early and embarked on an enthusiastic bender while I worked on his memoir titled, ironically enough, Surf for Your Life.

The footage is hard to watch, but harder not to. It’s the final of the J-Bay Open and Mick is up against his good friend and compatriot Julian Wilson, who’s just caught a long ride down the famed point. Mick sits alone and waits for a wave, all composure and steely focus, when there’s a sudden turbulence next to him. He looks confused, then alarmed. Then we see it. A large grey dorsal fin abruptly surfaces next to him as the turbulence intensifies. Mick is thrown from his board as the shark thrashes about, apparently (we later learn) tangled in his legrope. The surfing world holds its collective breath while the passing wave obscures him for long, drawn-out seconds. In that moment, I figure I have a better idea how he’s feeling than your average surf fan.

At Jeffreys Bay, the local beach commentator blasts the contest hooter to sound the alarm. Mercifully, Mick is plucked from the water by a jet ski unharmed, just as Julian Wilson has made the bold decision to paddle towards Mick and the white pointer menacing him, rather than away.

‘I figured I had my board, I could try and stab it or something,’ Julian offered afterwards.

All good, courageous, Aussie mateship at its finest.

But what really interests me is what Mick does in those few moments when he’s confronted with his mortality, when it’s just him and the shark thrashing about, before the cavalry arrives.

‘It was right there. I saw the whole thing and I was being dragged under by the legrope,’ Mick recounts on camera, only minutes later, still pinging on adrenalin. ‘I punched it a couple of times . . . I was swimming in and I had this thought, what if it comes to have another go at me? So I turned around so I could at least see it coming.’

When Mick flies home to Coolangatta, a media scrum is waiting, every bit as carnivorous as that apex marine predator. Everyone wants to know how he felt, what was going through his mind, how long it will take before he gets back in the water, if he will ever get back in the water (silly question, of course he will). News crews with satellite trucks camp out on the verge of his large, beachfront home. The inevitable 60 Minutes exclusive and silly internet memes soon follow.

I’ve never had a close shark encounter myself. But I do feel like I’m living through a slow-motion version of weirdly parallel events that began twelve days before Mick’s well-publicised brush with death. And I’m still thrashing about trying to work out how I might survive.

My great white shark is a balding, bespectacled urologist dispassionately informing me that not only do I have prostate cancer, but the cancer has already spread to my lymph nodes, my right femur (thigh bone) and left seventh rib. Or rather, my shark is those clusters of mutant cells swimming about in my blood stream and colonising my bones. There is the initial panic, the incomprehension, the wild flailing, the trying to process my dire situation, the desperate fight for survival.

I’ve known Mick since he was fifteen, and have written a book and dozens of magazine articles about him and his courageous rise to surfing greatness, hurdling one potentially career-ending injury or personal tragedy after another. As I watch those extraordinary images from Jeffreys Bay over and over, I think I might need to borrow a bit of inspiration from the champ. However much I want to flee, I’ll turn and face my shark, get a few punches in, do whatever I can to prevent it getting its teeth into me.

But there are no jet skis or rescue boats coming to pluck me out of my confrontation with mortality, no global audience witnessing my desperate struggle for survival. My fight for life will be played out privately, over years not seconds, and I will have to learn to live with this thing swimming around inside me for whatever time I have left.