- Published: 14 November 2023

- ISBN: 9781761342929

- Imprint: Viking

- Format: Trade Paperback

- Pages: 304

- RRP: $35.00

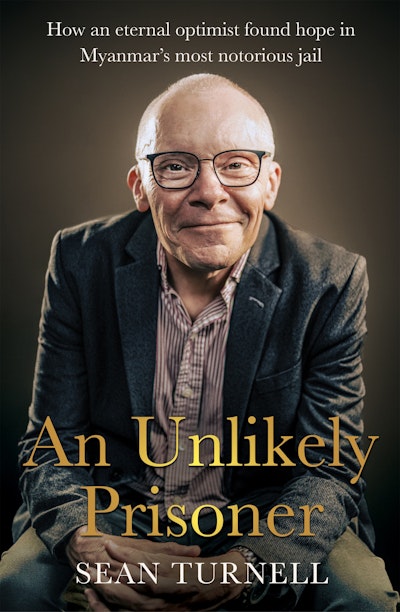

An Unlikely Prisoner

How an eternal optimist found hope in Myanmar’s most notorious jail

Extract

Dear Sean,

You do not know me, but a friend of mine who works at your hotel has just told me that since 4.00 this morning military intelligence and police have taken over the hotel’s security cameras. One of these is monitoring your door right now. You need to leave as soon as you can. Thank you for what you have done for our country. Please pray for us.

I had been expecting a message like this ever since the military coup in Myanmar the previous Monday, February 1.

Numerous government figures had been imprisoned, including the country’s civilian leader, Daw Aung San Suu Kyi – always Daw Suu to me. (‘Daw’ is an honorific for older women and women of stature.) While I usually kept my public comments to a minimum, I could not remain completely silent. Not when I had fallen in love with Myanmar years earlier, cared about its prospects, then proceeded to invest nearly 30 years of my life in the place – including living here for most of the last five as Daw Suu’s economic adviser. On the day of the coup, I had posted on Facebook a simple ‘Myanmar will shine again, but for now I am heartbroken’ with a backdrop of Yangon’s iconic Shwedagon Pagoda in the background. A day after, I thanked Facebook friends for their concerns for my safety, before writing that in Myanmar I had found the ‘bravest, kindest people I know’, who ‘deserve so much better’. This one featured a photo of myself with Daw Suu. The photo had been taken in a peaceful moment at Sydney’s Lowy Institute a few years earlier, but I felt our expressions of vague defiance seemed to match the new circumstances. The post ‘went viral’, the attention it drew no doubt helping to land me in hot water. My contacts in the UK, US and Australian embassies urged me to leave. There was, however, a hurdle: there were virtually no flights to be had. A small number of emergency charters had been scheduled, but these were already overbooked. I received a few vague promises that maybe one of these could be reopened for me. Nothing guaranteed. ‘Yes, Professor Turnell,’ said one airline representative, ‘we understand you are a high-value target.’

Heeding the message of my Secret Friend, I swiftly packed my bag and phoned Andrea Faulkner, the Australian Ambassador, to inform her of my situation. Almost a year into the pandemic, Myanmar was experiencing a surge in COVID-19 cases and I had been quarantining at one of Yangon’s nicest hotels since my return from a Christmas break in Sydney, so I set off to reception to check out. Frankly, I was not sure what I was doing beyond a fuzzy notion that before the soldiers and police got to me I might be spirited away to the Australian Embassy, where I could plan my subsequent escape.

On my way to reception, I made the first of a flurry of calls to my wife and fellow economist, Ha, in Sydney. ‘Don’t worry,’ I told her. ‘Chances are, the police are simply trying to give me a fright and hurry me on my way.’ I thought to myself, though, that if frightening me was their intention, it was working.

The instant I entered the lobby, I could tell something was up. Shadowy figures lurked in odd corners and I felt a sense of menace – it had a different quality to the anxiety that had settled into my body since I’d received the message. Even so, I strode up to the check-out desk and drew out my credit card: emergency or not, the economist in me required the settlement of a debt. As I did this, the posse assembled behind me; then the goons crowded in on me from the sides. Next thing, a police officer planted himself in front of me. So close I could smell his aftershave, feel his breath, notice his starched uniform. He appeared to be the Chief of the proceedings. Directing himself to the young woman at reception, he said in Burmese, ‘Professor Turnell must take a seat.’ They had, he explained, some questions. ‘It might take a while.’

More skulkers emerged from the periphery. Within moments, the lobby was heaving with soldiers, armed police and plain-clothes types with serious expressions, dark glasses, big watches, and complicated phones. At least two dozen, I guessed.

All of this was already dramatic at this early-morning hour. But then the drama amped up. First with the arrival of Ambassador Faulkner – in the Embassy limo, and with its Australian flag flying on the bonnet. Second, via the BBC World Service – who telephoned me just as I was being escorted to one of the lobby’s overstuffed armchairs. Could I speak, the producer of the Newshour program wanted to know. ‘Most certainly,’ I said. Somehow I managed to make the interview last nearly five minutes before an exasperated police officer snatched my phone away. Even this went live to air, however, and ensured – as I was to discover eventually – that for one brief shining moment, my arrest was the world’s breaking-news story. Much later I would learn that this interrupted call – in which my voice gradually becomes more and more guarded – was to become a broadcast staple in reporting on me.

Back to the drama, and something of a stand-off developed. Andrea Faulkner was firm, insisting on proper process every step of the way – something that discombobulated my soon-to-be captors. Together we slowed the process down, parrying the questions of the Chief and others who chimed in with lots of our own about why I was being detained and under whose authority. They responded with furrowed brows and fraught phone calls to Naypyitaw. The impasse did allow for two good developments though. First, my situation fast became news throughout the hotel, other hotels in Yangon, and then the rest of Myanmar. In foreigner enclaves and among politically connected locals, it conveyed a valuable lesson: if Sean could be detained, so could anyone. I was deeply connected to all sorts of decision-makers, local as well as international. A trickle of departures began. Several I observed that very morning: guests threading their way uneasily through the lobby, some escorted by their embassy staff. Bound for Yangon airport, or perhaps to cars for the dash to the contested areas and the Thai border, I supposed. I had mixed feelings about this. I was pleased my predicament was helping others. On the other hand, I was the one without a seat in the lifeboat.

Minutes and then hours passed, and the struggle between Andrea and me on one side, and my expectant captors on the other, continued. The staff of the hotel kindly brought me sandwiches and – presumably having noted my terrible eating habits – French fries. But I had no appetite. Perhaps I should have made myself have more: how intensely I would come to crave these fried bits of potato.

An immigration official appeared and demanded I hand over my passport. I told him he should look inside at the official visa I had been given by the Government of Myanmar, granted for someone working alongside the country’s key economic reformers. Of course, I understood that such approval from a government now largely in the cells was not much in the way of legal tender. But it was a bad moment, as anyone who has travelled will readily understand. Your passport is the one indispensable thing. Your talisman against threat. Your intersubjective validation of existence in the world of formal international process.

My phone, returned to me after the BBC imbroglio, was a source of constant sound – a symphony of pings from incoming messages. To some of these I was able to tap out a quick reply, noting the gravity of my situation while reassuring that, for now, I was physically okay at least. Ha was the major recipient of my texts and muted calls. I also spoke to my sister, Lisa Brandt, and my dad, Peter Turnell. They were worried but characteristically stalwart and ready to do whatever they could. Then my phone was taken away again, this time for good. I made a couple more calls to Ha via Andrea’s phone, but soon I was banned from using this, too.

To Ha, one source of information about what was happening remained. My friend Jo Daniels, an Australian lawyer also assisting Myanmar in its reform efforts, had managed to slip into the lobby from her room upstairs. She kept up a text commentary to Ha until evacuated by some quick-acting friends from the US Embassy.

What took place next was something I had been fearing: the seizure of my computer, iPad and memory stick. I was not asked to hand them over; they were simply taken from me. When I started to object the Chief dismissed me mid-sentence: ‘You will cooperate with us’. Since the coup I had been diligently going through my devices, deleting material that I considered confidential to the government with whom I had worked, and that I did not want to fall easily into the hands of these illegitimate and illegal usurpers. According to advice I’d obtained within hours of the coup, it was not really possible to eliminate documents on any electronic device, short of its complete physical destruction. It had been tough to absorb that information: the police, military intelligence (MI), and the thugs they worked for would use anything they could find against me. And what they couldn’t find, they would make up. The seizure of my gear was a turning point in my mind. This, I knew, meant real peril.

Mostly, after that, I sat. With two police officers sitting opposite and two others either side of Andrea and I, nothing but awkward small talk in broken English could really follow. Some dreadful banalities about the joys of Burmese cuisine, and why February was the ideal time to visit Myanmar. So cool and mild. More time passed, and with it went the morning and early afternoon. There was much shuffling about. At least half a dozen times I visited the bathroom. A police officer always came with me. I noticed among some of the police the embarrassed look of people who carry out orders that they know are wrong. Eventually, however, I noticed a change of tempo: the waiting was about to come to an end. The police announced to me and Andrea that they would be taking me away for more questioning. This would be to Tamwe Police Station, only about a kilometre north-east of the hotel.

Before being moved I was asked to open my luggage and take out all my casual clothing, toiletries and other essentials. They were stuffed into my small wheely-bag – one of those aeroplane carry-on bags. I didn’t think too much about this at the time, but in retrospect it was surely a sign that my detention in Myanmar was not going to be a brief one.

My feelings at this moment? Adrenaline-fuelled outrage and fear, coupled with an immense weariness and a sinking feeling that I was no longer in control of my fate. I tried to let none of this show, however: to make sure my hands didn’t shake as I shoved my possessions into the wheely-bag.

Then a frightening realisation: I had nothing to read! Just about all of my reading material was in electronic form and inside the devices the police had confiscated. Even my emergency reserve physical book, an historical account of the Royal Navy in the Napoleonic era, was taken away. When I asked for this back I was told it was needed ‘as evidence’. ‘Evidence of what?’ I asked. No reply. I was beyond the looking glass now.

At the last minute, Andrea grabbed a handful of newspapers on a stand in the hotel lobby and thrust them into my arms. Not all of them were recent, but it turned out that would matter little over the coming days. I would have been grateful for a cereal box to read. Stepping aside, Andrea told me the Embassy consular team would follow me to the police station. That I would not be alone.

A small crowd of police officers now surrounded me and gestured for me to move with them outside, where several police cars were waiting. I was escorted to an SUV of Chinese origin, all blue and white, with the truly surreal phrase, ‘May I help you?’ written on the side in English. The slogan had always struck me as ridiculous; now it seemed to mock me. Someone opened the back door, then one of the policemen shielded the top of my head – in that manner so familiar from TV cop shows – and I was bundled into the vehicle, wedged between two uniformed officers. They did not seem to be armed, but their toolbelts bulged with handcuffs, batons and other items of unknown – to me! – oppression. The SUV had an open back tray, on which two young police officers were perched. They were certainly armed. An automatic rifle each. Well-used, unmatched, and mean looking armaments of unknown provenance but deadly purpose.

In a show of courage and compassion that is characteristic of the people of Myanmar, the hotel staff lined the driveway to wave goodbye, and to signal their discontent at what was happening. I waved back. A good many of them were in tears, I noticed. Some raised their hand in the three-finger salute from the Hunger Games movies – a gesture adopted by people all over Southeast Asia to express unhappiness with their rulers, and much used these days in Yangon.

For Ha back in Sydney, my silence was a giveaway.

Through that morning, we had been reassuring each other that I would not be taken into custody – ‘This was not unexpected in the circumstances’ – that at worst I would be detained, but not for long . . . that I would be allowed to leave for the Embassy . . . I would be hurried to the airport. And, above all, ‘It will be all right.’

Much whistling in the dark.

Then the silence. I did not return messages, did not talk. The analogue world proved once more it has a way of intervening in our digital order. But the silence was also eloquent in its way, since it told Ha I had been taken away.

What should she do now?

For the moment, practical things. Talking with my dad, and with Lisa. Contacting Macquarie University to try to ensure my emails were secure. The Department of Foreign Affairs (DFAT) in Canberra called: Kim Lamb and Greg Wilcox of the Consular Operations Section. They confirmed I had been taken away. No new information, nothing yet as to the ‘where’.

The car journey to Tamwe was a short one, and although I saw protesters here and there, my faculties were too absorbed in apprehensive thought to notice much.

We arrived at Tamwe police station. A large rambling colonial-era building, it sat close behind a concrete wall in a small compound crowded in by trees. A big arched door at the front, a run-down lobby behind it, with offices running off either side. Inside, I could see cells down a dimly lit corridor. Very crowded cells. Many young people were in them, but all seemed to be in high spirits and completely uncowed by their surrounds. From what I could tell, most of the incarcerated were overwhelmingly ordinary Burmese citizens who had been arrested for protesting against the coup. They were armed with youth, the bravado that accompanies it, and that tremendous motivating spirit of being on the side of liberty and virtue.

From outside Tamwe police station came the sounds of a massive demonstration passing by. Banging of drums as well as pots and pans, and a grand chorus of voices singing Myanmar’s famous old protest songs. I knew all of these tunes from Burmese friends Australia, from an era of activism that everyone thought and hoped had come and gone. As the protestors passed what they knew to be the police station, the volume dramatically increased.

Self-pityingly, I wondered whether they knew I was inside. It transpired later, when I met some of these very same protestors in prison that they did, and some of the shouted messages were indeed meant for me.

A consular officer from the Embassy arrived at the police station soon after I got there and stayed with me for a while. I appreciated his presence. After ducking out briefly, he returned carrying a small roll-up mattress and a mosquito net. ‘For you,’ he said. The situation outside, he told me, was volatile. News of my capture was all over Yangon, and already banners bearing my Facebook photo with Daw Suu were being handed around.

In the prison office, meanwhile, all sorts of preliminaries were in play. Forms were filled out, photos taken, harassed-looking police officers marched in and out, all while a volley of agitated phone calls streamed in from what seemed to be higher authorities.

Eventually, all of this came to an end. It had grown dark outside. Curfew time was imminent. My consular officer departed, promising to be back at the police station the next morning.

What now for me? Well, it was time to be moved to a cell. Despite the overcrowding, one was cleared of other prisoners. In this, a pattern was set that would continue for the duration of my captivity in Myanmar. At all costs, the foreigner must not be allowed to contaminate the locals, enemies or not.

At this point too the police tried to take away my personal effects. My watch, given to me by Ha and Phuong at Christmas, my wallet. They wanted to take my wedding ring too. On this I stood my ground.

‘No,’ I told them. ‘I made a promise to my wife never to remove this. You are not taking it’.

They were taken aback. A silence followed. The policeman in charge who had been the principal form-filler earlier shrugged his shoulders.

‘Okay’, he said, ‘but they might take it later.’ I flinched inside. Who might ‘they’ be?

The cell I was led to did not constitute any favour to me. It was, to put things simply and honestly, a space of such filth and decrepitude that I am reluctant to sully the pages of this book with too detailed a description of it. Primordial muck – that I suspect dated as far back as the inauguration of the building – had created a layer on which I was meant to place my mattress and to perch my mosquito net.

And then I spotted it. A rat. An enormous rat. Now, I do understand that people exaggerate the size of these creatures, and this had been an exhausting and taxing day. Nevertheless, I am certain this rat was as big as a cat. Moreover, it was unafraid. Bold even, as it sat gnawing on something unspeakable in an especially grotty corner of my cell.

I hate rats. It’s a distaste I’ve always had, but that scene of the inhabitant of Room 101 in George Orwell’s 1984 had sealed the deal. And here I was, it suddenly occurred to me. In Myanmar, the haunting location of Orwell’s first brilliant novel, Burmese Days, and – according to most Myanmar people I know – all the rest of his novels, too.

Numbly, I settled myself as best I could. I prayed the rat would stay on his side of the bed.