- Published: 31 May 2022

- ISBN: 9781761042065

- Imprint: Penguin

- Format: Trade Paperback

- Pages: 368

- RRP: $34.99

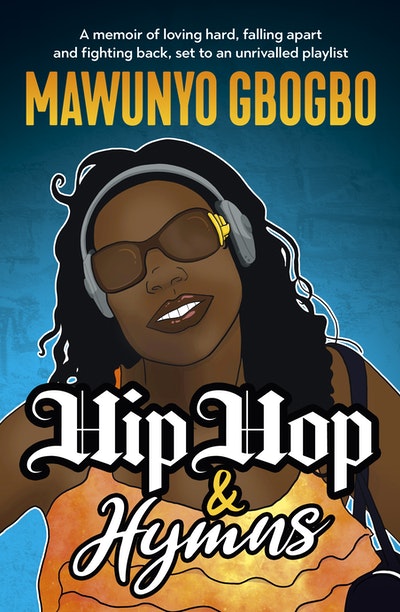

Hip Hop & Hymns

Extract

I’ve debated whether to tell this story at all. After all, it doesn’t cast me in the best light. But I’m sick of pretending to be someone I’m not. I’m sick of getting up every day, putting on my game face and living a guarded existence in which I’m not really me most of the time. I’m also tired of representing my race. And by that

I mean being on my best behaviour because – as is often the case – I’m the only Black person some people will ever meet. I just want to be me.

It’s not just the people I don’t know well. The first thing my mother said to me when I told her I was writing my life was, ‘Don’t embarrass me.’ But my objective is to tell my story honestly, without inhibitions.

This is also the story I wish I had available to me growing up in regional Australia, and I’m not alone in feeling that way. My Sydney hairdresser’s twenty-year-old daughter was helping her mother braid my hair when I asked her if she reads much.

‘No,’ she said. ‘Apart from textbooks that I have to read for uni, I haven’t read a book since I was a kid.’ There weren’t a lot of mainstream books being published that appealed to her.

‘What would you like to read about?’ I asked.

She giggled and, excitingly for me, outlined many of the themes in this book. ‘Romance, Black culture, societal issues pertaining to the Black race . . . and mental health.’

‘Do you want to read about Black people in other parts of the diaspora or here in Australia?’ I asked.

‘Here,’ was her reply.

This story is also a call to action. Because to be Black with heart is to rally against injustice. And it’s in that spirit that I’m telling my story. So, here I am. Unapologetically Black, and unapologetically real. Because I’m tired of caring about what everybody thinks.

Prologue - Lay Ya Gunz Down

If I only love once, at least I know I loved hard.

‘He’s a ratbag. You need to get rid of him.’

I’d dreamt about calling him mine. Wanted to be his girl. Now, both in our thirties, more than fifteen years after our first kiss as teenagers, we were officially an item – why would I give that up? He was my soulmate.

‘I’m worried about you, Mawunyo. You could be in danger. He’s just been shot, for crying out loud. You need to get him out of your life. The sooner, the better.’

I sat in my car on the phone to my friend Raquel. I had pulled over in the hospital car park after running a few errands but had the engine running to charge my phone.

‘I’ve never been in love with anyone but him. Even after all these years, I’m still madly in love. I can’t abandon him. I’m the only person who’s come to visit. I’m not going to walk away when he needs me most. Besides, I’m more of an influence on him than he is on me. It’s not like when we were teenagers.’

‘It’s not just about whether he’s an influence on you. You have to think long term. You can’t build a future with him. Imagine the type of influence he’ll have on your kids.’

‘He won’t be an influence on our kids.’

‘Of course he will be. He’ll be their father. They’ll mimic everything he does. They’ll adore him just as much as you do.’

That rocked me. My first instinct is to do everything I can to protect my children, even if they don’t exist, because they might exist in the future. The things Tyce had been through, the things he had done – these weren’t the sorts of things I wanted for our unborn kids. But in that moment, I chose to push his previous behaviour aside; it was all in the past. I wasn’t ready to let go of my love. My mother had called while I was on the phone to Raquel, so as soon as I hung up I called her back.

‘Mawunyo.’ Mum’s tone was thick with concern. ‘Are you okay? I’ve been so worried about you. I’ve been praying for you.’

‘Don’t you want to know if Tyce is okay? He’s the one who got shot.’

‘Mawunyo, he’s fine. He doesn’t need you. He’s a convicted drug dealer who’s had four children with two other women, and now he’s come back to you when nobody else wants him. He doesn’t care about you. If he did, he’d let you go.’

I was furious. I had already explained to Mum that he wasn’t a convicted drug dealer. At least, I don’t think he ever went to prison for that.

‘He does care about me. He loves me more than you do right now.’ I hung up.

I rejected her call a little later when she rang back but listened to the message she’d left, telling me she loves me no matter what: ‘I just want you to be happy.’ That meant a lot because there was something that made me happy, or at least someone: Tyce.

Tyce had been shot three days earlier by his friend Chase – who at the time of the shooting was presumably high. Tyce had walked in through Chase’s side door, like he always did, but this time instead of being greeted with a fist bump he was met with a bullet, which had lodged itself in his left leg, alongside a vein. An inch closer to that vein and he could have ended up paralysed, or worse: dead. When Tyce expressed his firm disapproval at being shot, reacting the way anybody would if a good friend had shot them, Chase asked him if he wanted another one in the chest.

Tyce wasn’t mad at Chase – he was off his head on drugs. Tyce had even asked me to pray for him.

I began walking towards the hospital. This was my fifth visit in three days. Tyce had already had surgery to remove the bullet and was doing well. I was staying at Uncle Bob’s Yallarwah Place at John Hunter Hospital, a cottage reserved for the family members and partners of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander patients.

When I walked into Tyce’s room, I found him sitting up in bed reading the Bible. You couldn’t make this shit up! Here was a man trying to better himself. A man who, despite adversity, genuinely wanted to turn things around and be somebody. He had troubles all around him, but he was not defeated – an example of God’s mercy if ever I had seen one. I had never been more in love.

He looked up at me and smiled. That smile. It always made my heart melt. And his chocolate complexion. Those dark, dark eyes.

‘Let’s get married,’ he said. ‘I don’t understand why you don’t see this as an opportunity. We’re at a hospital. There’s a chapel over there. There’ll be a pastor on site.’

It wasn’t the first time he’d expressed his desire to tie the knot, and I was all in. But in this setting? I drank in the white walls and white sheets, the beeping monitor, the sterile scent. I knew this wasn’t a proposal – he was just being playful – but at the same time I contemplated what it would mean to marry him at the hospital chapel. I thought about how much I’d always wanted to be his wife, how I’d longed to carry his child. After spending so much time together while I was on long service leave over the past five months, I knew our future wouldn’t be easy. We would face challenges most couples were shielded from. The kind of trauma my baby had been through, a cloud over our relationship. The hurt and pain I was carrying, a dagger in our joint prosperity. But we shared an undeniable love. We would have each other.

‘You won’t let me carry out just one little robbery so that I have enough money to marry you, so let’s just do it right here, right now.’

He was joking, of course. He was always joking. Or was he? I smiled as he put his hand over mine. My sweetheart, my one and only, my poison.

PART ONE

Chapter 1 – I Vow to Thee, My Country

A homeland so beautiful, it didn’t deserve to be left behind.

Before I was born, some crucial events took place, the results of which would play out over the years in devastating detail, crushing the players involved and injuring the bystanders. I was one of the bystanders, and my wounds would take many years to heal.

Ghana’s lush forests, broad beaches lapped by turquoise ocean and sparkling lagoons would form the backdrop of our family story, its natural beauty unable to camouflage the drama. Mum is from a royal family in Ghana. When Queen Elizabeth II visited in 1961, English royalty was greeted by African royalty: Togbui Nyaho Tamakloe III. Mum’s mother, my grandmother, was the youngest child of a chief, Togbui Nyaho Tamakloe I. He was a rich man who had lots of children, and adopted many more. These children were well educated and would go on to become doctors, lawyers and engineers, with many practising overseas. But it wasn’t just his own children he educated – he was famous for donating a massive parcel of land where the Zion College of West Africa, a secondary school, was built in the coastal town of Keta in the Volta Region, and another in Anloga.

My grandmother, Grace Adzoyovi Amegamenui Tamakloe, was a beautiful woman. She was kind, generous and highly respected. She had a son with her first husband, and after he died, she married my grandfather. They were in a polygynous relationship; she was one of about eight wives.

Mum’s dad, my grandfather, Abraham Kofi Amuzu Hotorwovi Amegadze, was a farmer who was gifted in healing people. When the sick came from afar to seek his help, he would pray to Almighty God in heaven, as well as the little gods in the form of statues on his property, and then use herbs to heal them.

Mum was very close to her father. She loved him so much, and he favoured her too. He was an industrious man, who was planting coconut trees one day when a man approached.

‘You’re old and you’re planting these trees. Won’t you die before you even get the chance to harvest them?’ ‘If I die, my children will harvest them,’ my grandfather said. But not only did he live to harvest the coconut trees, he sent the coconuts abroad to London, where he sold them, the profits bringing him a handsome sum of money. He passed this lesson down to my mother – she should never think she was too old to do anything – and Mum would pass that same lesson on to me by example.

The fifth of December, 1958, began like any ordinary day for Mum, eleven years old, getting ready for school and sitting down to eat breakfast.

‘I don’t want you to go to school today,’ her father told her. ‘Stay at home with me.’

‘But why, Pappa?’ Mum looked up at her father as she ate her porridge.

‘If you go to school today, when you come back, you will come and see me at Whuti.’ The family cemetery was at Whuti.

‘Oh please, I want to go. We’ll get our exam results back today. I want to know how I went.’

‘Okay, go,’ my grandfather said, ‘but you won’t see me again when you return.’

Mum thought about her father all day at school, and while rushing home she ran into her brother and one of her cousins. ‘Where are you going?’ she called out. She could tell by their demeanour that something was wrong.

The two boys looked at her and then looked at each other.

‘Oh, God . . . Pappa died? Pappa died?’ Mum’s heart was beating faster and faster.

‘Yes,’ her brother said, ‘but don’t tell anybody yet. He’s a very important man. We are on our way to Anloga to make preparations for his funeral—’

Mum didn’t hear the rest of the sentence. She threw her school bag and started howling. Her brother walked over, picked the bag out of the bushes and watched as his sister ran as fast as she could back to the house.

Mum saw her father’s lifeless body tucked into his bed at home. ‘No!’ she screamed, tears streaming down her face. ‘Oh, Pappa, wake up!’ By then a group of people had gathered, conscious of the young child in the corner who continued to bawl. A man Mum barely knew snapped at her.

‘You,’ he said, pointing. ‘Your father said don’t go to school, because he’ll die today. You went to school. How naughty can you be? We will put you in the same coffin as him and bury you too if you don’t stop crying now!’

She looked up at the man, her eyes wide with fear.

Mum was overcome with grief and cried herself to sleep night after night after night in the wake of her father’s death. She didn’t own a diary, so she wrote on the wall in the bedroom she shared with her mother and siblings. My father died on 5th December, 1958, ndokutsu. She was unsure how to spell the word ‘afternoon’ in English.

Because she had lost her father so suddenly, Mum was always worried about her mother. My grandmother lent money to anyone who asked – usually fishermen, who would buy food to eat before going out to catch fish, but it got to the point where she would lend huge amounts of money to people who stopped paying it back, hurting her financially. She also couldn’t understand how people could take advantage of her kindness and compassion, exchanging it for contempt.

When Grandma Grace ventured out to ask for the money back, she would return home disappointed and would get very sick. Mum was scared, not wanting to lose her mother as suddenly as she’d lost her father – so despite her mother telling her to go to secondary school, she chose not to. She wanted to work and do what she could for her mother.

One day, when Mum was seventeen years old, she was walking a fair way in the capital, Accra, looking for work, when a car screeched up beside her. A white man, or as Mum would refer to him, ‘an Englishman’, hung his head out the window and asked her where she was going. She told him and he offered her a lift.

The white man took a detour, via his own house, before dropping Mum off. It took her a while to work out what on earth this white man was doing as he reclined on his couch in front of her. She realises now, he was masturbating.

He would do something afterwards, however, that would change the course of Mum’s life. Before they parted ways, he handed her 10 shillings. Mum used those 10 shillings to buy a Bible at the Methodist bookshop in Accra. There was nothing else she wanted more. Her spiritual journey continued in earnest that day.

~

In another part of Ghana’s Volta Region, my father, at eight years old, was the only surviving child of his parents, Lumor and Amekakporm. Two older sisters had died in infancy and a third girl, born after him, also died as a baby. Dad’s father was a miller and his mother would grind corn into a paste, cooking akple to sell at market. Dad didn’t live with his parents, who were in Mankrong Junction. He was being looked after by his grandmother – my great-grandmother – Mamaga, in the tiny village where he’d been born, Akplorfudzi.

Grandfather Lumor instilled in Dad early on that education was the key to getting ahead. But Dad didn’t like school. He preferred to skip class and go fishing with his classmates. He wanted to be like his dad, who he thought was doing well for himself. But Grandfather Lumor hadn’t had much of an education himself and didn’t want his son to be a corn miller too. He wanted him to achieve so much more.

‘If you don’t want to go to school, you shouldn’t have to go,’ Mamaga told Dad, who had been busted truanting. ‘I never went to school and I’m alright.’

‘He will continue to go to school,’ Dad’s mum, who was visiting, said.

Dad jumped out of his chair and clung to his mother. ‘I want to go to Mankrong Junction with you.’

‘No.’ His mother disentangled him from her dress.

Later, the trio walked down to the river, which flowed behind the house. Dad frowned as he watched his mother board a canoe and wave goodbye. Tears slid down his face as the canoe slipped away into the distance.

Dad continued to pester Mamaga until his mother’s next visit, adamant that he wanted to leave the village and join his parents at Mankrong Junction.

‘He’s not happy here,’ Mamaga told her daughter. ‘He’s been crying and abusing people. He’s had enough of the village. He wants to be with you and Lumor.’

‘You know it’s not practical.’ Grandma Amekakporm looked at her mother. ‘The language is different. Lumor and I are always working, and he has been at the same school since elementary.’

Dad walked into the room. ‘Ete,’ he said to his mother. ‘Can I leave with you?’

‘No. You’re to stay here and that’s final. The canoe will be leaving shortly. You can come and see me off.’

Soon afterwards, they walked down to the river. Dad jumped up and down, yelling, sobbing, saying he wanted to go too. His mother put her finger to his lips.

Dad watched as his mother’s canoe left the shore and made its way downstream. He tore himself away from Mamaga and ran, jumping fully dressed into the water. He tried desperately to reach the canoe. He didn’t know how to swim and splashed his way through the water, arms flailing wildly, as the canoe pulled further and further away.

Dad didn’t get very far before a group of bystanders who had witnessed the commotion jumped into the water and pulled him back to shore.

An old man restrained him while others from the village chastised his actions.

‘“It takes a village to raise a child” is a true African proverb,’ Dad would tell me much later. ‘If you misbehave, anyone who knows your parents will discipline you, then they’ll tell your parents, and your parents will thank them and discipline you in addition.’

Grandma Amekakporm saw what happened from the moving canoe and told her husband when she arrived back in Mankrong Junction what their son had done.

‘Okay, the boy has grown up,’ was his reply, and he decided then that Dad’s time in the village was over. On his mother’s next visit, Dad left with her to join his parents at Mankrong Junction, where he would at first struggle to learn the new language, before mastering several.

~

Mum and Dad were just friends for some time after they first met. Things shifted when Dad’s employer – the Electricity Commission of Ghana – sent him to Germany for a practical training attachment. He and Mum exchanged many letters and their relationship blossomed. He told her he wanted to settle down and start a family. He was in his early thirties and his parents were gently pestering him for grandchildren. But Mum was in two minds.

She had worked her way up from being a ward assistant to an enrolled nurse at Tema General Hospital in the Greater Accra Region, but her desire was to become a registered nurse. In order to do so, she would need to go away to study in Tamale, the capital of the Northern Region. The two would be away from each other for some time. In the end, Mum agreed to marry Dad, but insisted on going away to pursue her dream. As a symbol of their engagement, Mum asked Dad to give her some money so she could buy a ring in Accra – a humble gold band, devoid of diamonds.

Dad’s mother died while he was in Germany, and he stayed with Mum when he returned to Ghana for the funeral. When his overseas training wrapped up, he was posted to Tarkwa, in Ghana’s Western Region, as the officer in charge. It meant Mum and Dad were a daytrip away from each other.

The first time Dad visited Mum I was conceived in a hotel room in Tamale where Dad was staying. Mum was very sick when she was pregnant with me. She was diagnosed with hyperemesis gravidarum, a severe type of morning sickness, and even the sight of most foods would make her nauseous and vomit. Mum’s sister, my Aunty Rita, was by Mum’s side throughout her pregnancy.

When Mum’s illness resulted in her being hospitalised, Dad paid her a visit.

‘What’s wrong?’ Dad asked.

‘Oh, God, I’m pregnant.’

‘Why didn’t you terminate the pregnancy?’

‘What?’ Mum couldn’t believe what she was hearing. ‘You told me you wanted to marry me, and I’m pregnant. And you want me to cause an abortion. Why?’

Dad’s thinking was that Mum was only a year into her three-year degree. Her pregnancy would mean she couldn’t continue. He had warned her not to blame him if anything happened.

Mum was five months pregnant when she went to visit Dad in Tarkwa with her niece, Lucy. They were at Dad’s place when he delivered some news that would unsettle Mum and be a catalyst for years of heartache and distress to come.

‘I have a baby son,’ he said.

Mum thought he was joking. When he left the house to run an errand, Mum told Lucy just how humourless she thought the joke was.

‘Listen, Aunty,’ Lucy said. ‘This is no joke. He said this to you – how can this be a joke?’

While Dad was away, Mum, still reeling from his words, got up and walked over to the chest of drawers in his lounge room. There were always letters sitting on top of the cabinet, which she had never before examined closely. But she wanted to see if she could find any evidence to support Dad’s claim – or, she hoped, dispense with it as one of the worst jokes in history. Dad did joke around a lot. It was one of the things she liked about him, the way he could make her laugh.

Mum experienced a mix of emotions as she read a letter from one of Dad’s cousins. In it, she discovered Grandfather Lumor didn’t like her. He wanted Dad to marry ‘the woman who had a boy for you’ instead. Mum’s interpretation of the letter was that Dad had been defiant, insisting on staying with his ‘Anlo girl’, Mum. He must love me, she thought. He was facing pressure to stay away but chose not to.

When Dad returned, he was apologetic as he filled in the blanks about his son, Selassie. Spelled differently, Selasi means God has heard my pleading in Ewe, my parents’ native tongue.

Mum did the calculations and realised Selassie’s mother must have been five months pregnant when Dad had come to see her and I was conceived.

‘If you didn’t want me, you should have told me,’ she said. ‘This is too much. You should have told me that you have someone already, but you came – I was in college and you came and did this to me when you knew you already had someone who was pregnant. If you didn’t know, that would be different. But you knew. What you did is so cruel.’

‘I’m sorry,’ Dad said. And Mum, as hurt as she was but with the knowledge of what she’d learned in the letter, believed his apology to be sincere.

Mum didn’t end up going back to her studies in Tamale. She returned to Tema instead because she was so sick. Her dream to become a registered nurse was put on hold.

Aunty Rita provided a shoulder to cry on and an ear to confide in during this period. Mum also leaned on Lucy and friend Aurelia, who’d bought some maternity dresses for her.

Mum’s obstetrician wasn’t there the day I was born at Tema General Hospital. Instead, one of Mum’s colleagues, Dr Lawani, was on duty.

‘If you haven’t had this baby within an hour or two, we will have to take you in for a caesarean section,’ Dr Lawani said.

Mum looked at him. They were close, having worked together, but she knew he had never performed a caesarean section before. When he left, the pain was so severe that the nurses started to prepare her for theatre.

‘Your baby is suffering foetal distress,’ Dr Lawani explained. ‘Your baby’s heart is racing. It’s time to head to the operating theatre.’

Mum said a prayer. ‘Lord Jesus, it’s not Dr Lawani who is going to do this operation – you take the knife and do this.’

I was blue when I was born, from lack of oxygen, but soon recovered after being given a few lungfuls from the staff. Dr Lawani was so proud of delivering me – he bragged to all the nurses, who were calling me Baby Precious, or Baby P. for short.

One of the women who lived in Mum’s building was shocked when she learned what Mum had decided to name me: Mawunyo. It means God is good in Ewe.

~~~

Check out the Mawunyo Gbogbo's Hip Hop & Hymns Spotify Playlist to accompany the book.

Hip Hop & Hymns Mawunyo Gbogbo

A memoir of loving hard, falling apart and fighting back, set to an unrivalled playlist.

Buy now