- Published: 1 May 2017

- ISBN: 9781760140786

- Imprint: Penguin eBooks

- Format: EBook

- Pages: 272

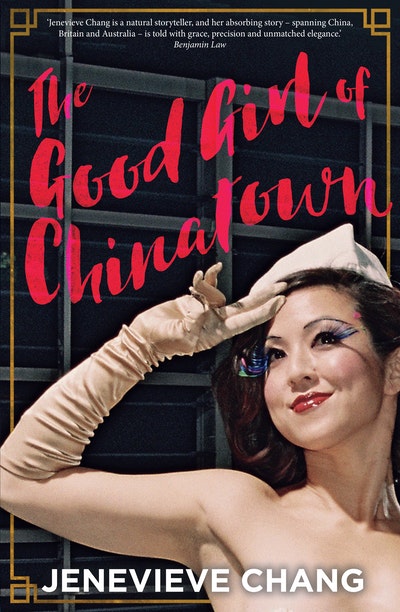

The Good Girl of Chinatown

Extract

A note awaits me on the dining table, scrawled in a series of cursive exclamations.

Morning darling!

Take a shower when you get up! You threw up on yourself just before I put you to bed. Love you! Marilou

I shower and scrub quickly, watching the suds drain out of the tub. Despondent eyes stare back at me in the mirror as I scrape my hair into a ponytail. Back in the bedroom, I pick up yesterday’s dress from off the floor: Chanel caked in stomach matter. I skip breakfast, grab a coffee, and head out the door.

Out on Xizang Lu, I hail a cab and sink into the sweaty upholstery.

‘Wo ke yi chou yen ma?’ I ask.

By the time the driver grunts in compliance, I already have my lighter out. I inhale and blow smoke into more smoke outside as I lean back and wait in vain for the lurching in my belly to stop. Shanghai’s summer air clings like a needy lover.

The street I live on stretches to People’s Square – two shiny blocks with vestiges of the old world resisting the encroachment of the new. Elderly men pull carts selling wooden back scratchers in front of blinking, chiming, flashing electronics super malls. Stalls of steaming baozi promise sustenance to sharp-suited bankers coming in for another Sunday at the office.

It is a short ride from corporate People’s Square to weary Qipu Lu, before flattening out into Hongkou – which means ‘red mouth’. Once a former Japanese concession before turning into a Jewish ghetto for stateless immigrants fleeing Hitler during the last world war, today’s Hongkou is a labyrinth of narrow streets flanked with pushbikes and bamboo rods flying underwear like triumphant flags. We pull up outside a former Buddhist shrine. The cobbler by the entrance offers up a toothless smile.

Every major city in the world has a Chinatown where a time-capsuled East lives inside a contemporary West. This Chinatown – my Chinatown – does the reverse. This is where a nostalgic West exists inside a modernising East. My mobile phone beeps for attention. It’s Giles.

Jenevieve! Where did you disappear to last night? Do you remember the Flirtinis? Do you remember the third-floor bar?!

I dial his number and he picks up straight away.

‘Hey, are you okay?’ His London vowels are subdued, concerned. But also a little amused.

‘What happened last night? I thought . . . you, we . . . that is . . .’

‘Me too. I went to get your things and when I came back, you were propped up between Marilou and Elroy heading out the door.’

‘Oh.’

‘Do you remember the third-floor bar?’

‘What about it?’

‘We had . . .’

‘We had what?’

‘Sex. On the couch. After you asked people back to my place to watch us have sex.’

My body jolts like I’ve walked into an electric fence.

‘If it’s any consolation,’ Giles continues, ‘you looked like you were having a really good time.’

I turn my phone off. I’m late for rehearsals.

I step into Chinatown. There are three whole days before the club opens to the public again and it’s transmitting a distinct ‘morning after’ vibe. Glasses are stacked along the bar and ash sprinkles the black and pink floors. Red velvet curtains are pulled open across the Victorian stage, revealing strewn props and discarded clothing. The fleur-de-lis wallpaper has begun to curl from one of the banquettes.

I shouldn’t be here. It’s been three months since my last paycheque. But I’m not the only one. In fact, for whatever reason – sentiment, fear, misguided loyalty – we have all stayed. As an international showgirl troupe called the Chinatown Dolls, it seems that teasing an unsuspecting audience while everything else falls apart is preferable to admitting that our great China plan has failed. So here I am – barely standing, but ready to perform again.

Today’s rehearsal is a departure from the usual song and dance. In a bid to attract a different audience, Chinatown has decided to stage some high society theatre from Noël Coward. I’m fine for most of it, but when I have to speak the line ‘Alcohol will ruin your whole life if you allow it to get a hold on you, you know!’, I burst into tears and run offstage, almost knocking over our ayi in the process. As I dry my eyes in the dressing room, I hear her tut-tutting under her breath, ‘Chinese face, foreign mind! Always cry-cry, shout-shout, drink-drink, take off clothes . . . Ai-yah! ’

By the end of the day I am exhausted but have somehow made it through a run of the second half of the play. Tactfully, everybody avoids eye contact as we take our director’s notes but Charlie can’t help himself. ‘Today has been an interesting experiment into the efficacy of the human liver, don’t you think, Jenevieve?’

It is dark by the time I return home. Just as I’m curling back into bed, the phone rings.

‘Sweetie . . . how are you?’ Marilou’s Southern voice trickles like syrup down the line. Then she launches into a blow-by-blow account of the previous night. ‘So we got to your apartment in the cab . . . you were really sick and rolling your head back. And then you kept leading me to the wrong floor. You took me to the third, then the twenty-third before I finally recognised your door on the twenty-first floor. Then when I was putting you to bed, you vomited all over yourself. I had to strip you off, and then you passed out cold on your pillow. Sorry I couldn’t clean you up, but the taxi meter was still running outside.’

‘What happened with Giles?’

There is a brief, surprised pause. ‘You begged me to take you away from him.’

‘Really?’

‘Yeah. Your exact words were “I’m going to be sick, and I don’t want him near me. He’s not good for me anyway if I have to get like this to go home with him every time.”’

Wow. Maybe my drunk self was smarter than I thought.

Hanging up, I slide open the glass door and step outside. The breeze has an unexpected chill. From the edge of my balcony, Shanghai spirals out like a serpent, coiling its way out to the Bund around a choking, madly pumping heart. There are no stars in the city, only millions of lights illuminating people’s homes, offices and the spaces in between. At that moment, I realise that the choking heart is mine – a thought that slices through me like a knife. Suddenly I’m shivering, my body collecting with tears that begin rolling down my face. I barely recognise the mournful sounds piercing the night air. I clutch at the stitch radiating along my ribcage as I wait for the convulsing to stop. The drumming inside my head gradually softens into a whisper: stop running away.

Despite my shaky legs, I pull myself straight. From where I’m looking, there are two ways forward: one is a sheer drop into oblivion; and the other is to go back. To retrace my steps. And remember what came before.

I turn around and lock the glass door behind me.

The Good Girl of Chinatown Jenevieve Chang

A true story of cultural clash and hedonism gone awry as a good girl from a conservative Chinese-Australian family becomes a Shanghai showgirl.

Buy now