- Published: 19 September 2016

- ISBN: 9780143797302

- Imprint: Michael Joseph

- Format: Trade Paperback

- Pages: 320

- RRP: $35.00

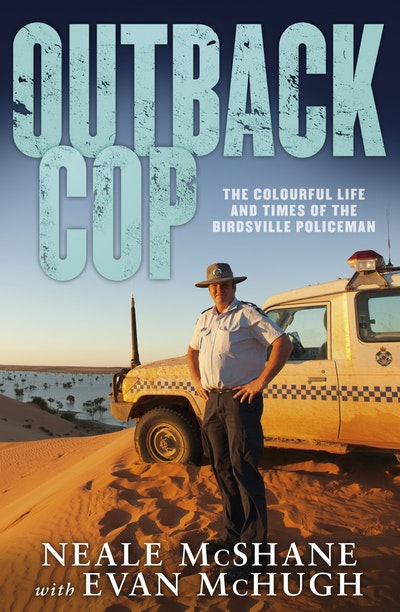

Outback Cop

Extract

You can guarantee you’ll get a dust storm just after you’ve cleaned the place, too. Nevertheless, sweeping dust is part of the job. You clean the house. You clean the police station. Then you do it all again.

And there were flies. You couldn’t go out for a walk during the day without being covered. You could drive out into the middle of nowhere, nothing and no-one for hundreds of kilometres, and within seconds you’d have hundreds of them trying to be your best friend. It made me wonder what they all did before I came along.

My first experience of Birdsville was a fair shock to the system. I thought Charleville, where I was a prosecuting sergeant with the Queensland Police Service, was hot because it’s in the middle of Queensland. It’s regularly 40 degrees. I thought it might be a couple of degrees warmer in Birdsville but you don’t realise how much hotter it is until you actually get there. It’s just oppressive.

But everyone knows Birdsville. I’d been here once because I’d brought a house out here. Not bought, brought. Out here they transport houses from place to place and I was escorting one of those. They load them onto huge semitrailers, sometimes they cut them in half, but they can be so wide they need a police escort to warn oncoming traffic, supervise removing and replacing road signs and to ensure that nothing gets damaged along the way.

The town is on the eastern edge of the Simpson Desert, in the south-west corner of Queensland, near the borders of South Australia and the Northern Territory, and it really is the land of plenty: plenty of heat, plenty of dust, plenty of flies.

The population is seventy to a hundred permanent residents during the cooler months, when tourism is a major part of the town’s activities. Over summer, that can drop as low as forty as things wind down and people take holidays to escape the heat. The town is also surrounded by cattle stations that measure in the thousands of square kilometres. For much of the year, it’s a sleepy little outback town like any other. However, it’s also famous for its iconic outback pub, the Birdsville Hotel, and for its annual horse races, which see the population increase a hundred-fold for two days at the beginning of September. Being on the edge of the Simpson Desert, it’s also the starting point or destination for four-wheel drive and off-road motorbike adventurers hoping to tackle the hundreds of kilometres of sand hills that surround the town and extend far to the west, south and north.

I initially thought being the Birdsville cop wasn’t for me. The job was advertised three times before I put in an application. The position was for a senior constable and I was a sergeant (a rank above) at the time, so I thought, Nah. I didn’t even think about putting in for it.

Then, a month later, it got advertised again and the superintendent from the Mount Isa District put a spiel out: come to Birdsville, this is what we offer you. And it’s got all these perks. Then I considered it, but I thought, What about my family? We’d been separated a few times before because of work, and by this stage my daughter, Lauren, was finishing her final year at school. Anyway, for a second time I thought, Nah, I’m not putting in for it.

Then it was advertised for a third time, with another spiel: come to Birdsville. And I thought, I’m gonna put in for it. I was fifty years old and I had nine years to go with the Queensland Police Service before I had to retire (the compulsory retirement age in the QPS is sixty). I thought, That would be a good way to finish my career. I’d never been an officer-in-charge of a police station.

So I spoke to my wife, Sandra, and we came out and had a look at the place. The whole town was dry and dusty and practically deserted, as it was getting into the hotter months and the tourists were few and far between. When there aren’t many people around, it feels more remote than ever.

We went through the house, which was carpeted at that stage. The carpet was full of dust and crushed-in dirt. Sandra went around to look at something and I came out and the copper who was there, who was relieving at the time, he said, ‘She doesn’t like it, does she?’

I said, ‘Yes, she does.’

He said, ‘Nah. I can tell she doesn’t like it.’

And he was right. Police are pretty good at that.

Nevertheless, the job had lots of attractions. I looked at the crime figures: virtually none. Traffic accidents? Probably four or five a year. A good community. You had the races. Obviously the hotel. You had the house, which was free. They gave you extra money for being here.

So, I had nine years to go with the police, and it was either Birdsville or go up to senior sergeant. And I’d done that, relieving at Cunnamulla, a town about 200 kilometres south of Charleville, but you’ve got all the issues that go along with being senior sergeant: people management, budget, blah blah blah. And I didn’t want to do that again.

I wanted a change from prosecuting, too. I’d spent ten years representing the Queensland Police Service in court for everything from traffic tickets to serious crime. Sometimes you get a case, like a murder committal, and you’re up against the best barristers in the state so you’ve got to really prepare, you’ve got to listen to every word. Or you can run into trouble when witnesses don’t turn up and you’ve got to try and find them. It’s just stressful. Nothing runs smoothly. Honestly, in prosecutions, nothing runs smoothly.

If you win, it’s because the police officers involved put together a good brief. If you lose, it’s the prosecutor’s fault. One or the other. Then you’d have a win and you’d get the police you were representing saying, ‘Well how come he didn’t get jail?’ They don’t realise that if you negotiate a plea they have to get a discount. Sometimes you have an aggrieved, a victim, who doesn’t want to give evidence, so you try to get a successful outcome where they don’t have to. The deal might be that you don’t ask for a term of imprisonment or something like that. And any plea you negotiate has to be approved by the inspector anyway. That didn’t stop me getting nicknamed Do-a-deal-Neale.

In hindsight I’d probably had enough of prosecutions. It’s a desk job or you’re in court, negotiating with police, lawyers and magistrates. There’s not much opportunity to engage with the rest of the community. When I’d done some relieving as officer-in-charge at the famous little opal town of Quilpie (population 570, compared to Charleville’s 3000 and Birdsville’s 70) I’d found that working in a small community was much more appealing. Something happens, you’ve got to deal with it. It can be people having to land a damaged plane, which thankfully in most cases is just a landing-gear light not working. You know what that’s like.

You can have people die. That’s life, people have accidents. And you can bet your bottom dollar, in ten years, there are going to be two or three deaths in town. You’ve got to deal with all that. If there’s a fire, you’ve got to deal with it. Missing persons. You’ve got to go with what you got.

Sandra and I spent quite a while talking about it, and eventually we struck a deal. I would come out, then our daughter Lauren would join me once she finished high school and take the QGAP job. QGAP is a one-stop State Government shop that provides a suite of government services such as car registrations, applying for housing, and so on. Lauren wanted to have a gap year so she could come out and work with me, doing the QGAP job for sixteen hours a week, and I’d look after her, being her dad. Sandra would stay in Charleville with our youngest son, Robbie, while he finished school. He still had a couple of years of high school to go and didn’t want to go to boarding school. We didn’t want him to go either. It was far from being an easy decision: effectively splitting up the family and having to spend long periods apart. Sandra and I both loved family life and each other. The job in Birdsville wouldn’t mean the end of that but it would involve some major changes in all our lives.

There were other considerations, too. We’d bought a Queenslander in Charleville a few years earlier and Sandra could finish doing it up, get it painted. She was also working as a probation parole officer part-time and working at the Cosmos Centre as a guide. Our oldest son, Andrew, was already doing a carpentry apprenticeship in Brisbane after returning from three years in the UK.

Lauren coming out here was probably the clincher. She didn’t want to go straight from school to uni. I didn’t think she was ready to leave the nest but that may say more about me than it does about her. So if Lauren came here, she’d be with me. And Sandra had a job in Charleville, and Robbie. Lots of people have long-distance relationships: miners, pilots, whatever. So Sandra could fly out when she was on holidays or for big events. It was probably $300 return in those days, which wasn’t a large amount of money. Robbie could come out all the time, too, and I’d go home whenever I could. We’d see each other on a semi-regular basis. It would work out.

I said, ‘We’ll take the job but the carpet has to go.’ (Laughter)

There were a few other things that I requested before I agreed to move in, and they did all those. They put the lino in and I took the job.

Heading out to Birdsville in late 2006, I said goodbye to my family and headed off from Charleville in my trusty 1996 Toyota Land Cruiser. I drove 220 kilometres to Quilpie, then 245 kilometres to an even smaller town, Windorah. I dropped into the police station at Windorah and introduced myself to the officer, then Senior Constable Jim Beck. I had a cuppa and yarn with Jim, as Windorah was going to be my neighbouring station when I got to Birdsville, albeit 400 kilometres away. I had a feeling we would have a lot to do with each other, and I was right: overdue tourists, accidents, criminals, joint patrols, you name it.

I filled my car, checked it and headed off. I had just shy of 400 kilometres to travel, the first 100 kilometres single-lane bitumen then the rest gravel roads. I travelled for hours without seeing another vehicle. Finally, I spotted dust coming towards me.

I laughed when I saw it was the furniture removalists who had taken my furniture out to Birdsville on their return leg. I stopped and had a yarn to them. It was good to talk to someone. I said goodbye, headed off again and six hours after leaving Windorah I went over a sand hill and saw the famous Birdsville Race Course on the right-hand side. Ah, made it.

By this time it was late afternoon. It was very hot and dusty. The whole town was brown with no green. Even the trees were brown from the dust. There was no-one about. One four-wheel drive was parked outside the pub. I went to my house. Fortunately, Inspector Trevor Kidd had arranged for it to be thoroughly cleaned before I arrived, as no-one had lived in it for almost eight months. The fridge was on and all the furniture was in place. There were still heaps of boxes to unpack. There was no police officer to welcome me. There hadn’t been one in Birdsville for weeks and weeks. The keys to the police station and vehicle were on the kitchen bench.

Prior to going to Birdsville my plan was to stay till retirement, a decade in the future. I thought, Well, I’m here now. I unpacked the vehicle, turned on the air conditioner, cracked open a beer and wondered what the next ten years would bring.

Outback Cop Evan McHugh, Neale McShane

'Birdsville, the land of plenty – plenty of heat, dust, flies, snakes, camels and salt of the earth outback folk.' Neale McShane

Buy now