- Published: 4 August 2020

- ISBN: 9781760899455

- Imprint: Penguin

- Format: Paperback

- Pages: 336

- RRP: $26.99

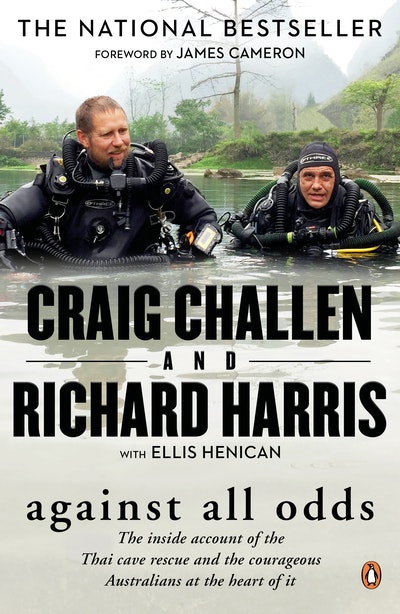

Against All Odds

The inside account of the Thai cave rescue and the courageous Australians at the heart of it

Extract

Foreword

The world was riveted by the news coming out of Thailand. Twelve local boys and their soccer coach trapped by early rains deep inside a cave system, cut off from the outside world, imprisoned in absolute darkness, with little hope of rescue. As rescue efforts escalated, ultimately bringing in thousands of rescue experts, divers, military and throngs of media, the situation only seemed bleaker by the day. The boys were found alive by two British cave divers who pushed through strong currents and zero visibility over four kilometres into the bowels of the mountain, but the rains were coming soon, which would wipe out all hope of extracting the stranded soccer team.

An outpouring of empathy from around the world kept the media spotlight focused on the mouth of that cave, where rescue workers, authorities, military, the distraught parents, and all manner of supporters and lookieloos had created an ad hoc city.

But a disturbing paralysis had set in. Yes, we know where they are. But how to get them out through miles of flooded tunnels?

As the hours ticked down, each plan seemed more desperate than the last.

Pump the water out? Rough mountain terrain prevented the kind of high-volume pumps necessary from being set up, and several people were injured trying. Dig a borehole down from above? Hundreds of holes were drilled, and none managed to sharp-shoot the cave the boys were in. Leave them inside until the monsoon season ended? But how to keep them warm, fed, healthy – and sane – for months, far underground? Teach them to dive and swim them out? But how could an assortment of average teenage boys all be taught the complex skills that cave divers took years to learn, in just hours, and in a remote, flooded cavern?

It was like a nightmare in slow motion. And it was in that nightmarish equipoise that Australian cave divers Richard ‘Harry’ Harris and Craig Challen joined the rescue effort.

The unique combination of their advanced cave-diving skills and their day jobs as doctors made them suddenly the most important members of the proposed rescue mission. That combination propelled them forward over just a few days from watching at a distance like the rest of the spellbound world, to becoming the tip of the spear of the final rescue. Why them? Because the more the rescue scenarios were analysed, the more it became clear that the boys would have to be somehow sedated, and brought out of the cave unconscious, for both their own protection against deadly panic, and for the protection of the rescue divers.

So the spotlight swivelled to the two guys in the international cave-diving community who were also experts in anaesthesia.

Now I’m not a cave diver. But I count a few top cave divers as friends, and I was taught cave diving by Wes Skiles, the famed National Geographic photographer, which is a bit like being taught to play tennis by Serena Williams. My couple of days diving the gin-clear spring-fed caves in Florida gave me more than enough respect for the divers who venture miles into flooded caverns – sometimes freezing, sometimes in zero-visibility water, and sometimes down to extreme depths – in their quest to see and explore beyond the limits of the known world.

I have enormous respect for the focus, intelligence, courage and physical strength required to do it. And as an explorer myself, I understand that illogical but irresistible urge to go as far from the warm, cosy centre of human experience as possible, to get to the very edge of what is known, and then go beyond it. If you’ve got that explorer gene, there is no thrill greater in life than to see that which has never been previously gazed upon by human eyes. That, first and foremost, drives us. A very close second is to survive and return to tell the tale. In my case, bringing back the images to support that narrative is also a very high priority, just below survival.

I’ve spent thousands of hours under water, many of them inside shipwrecks, at least 500 of them in diving helmets, another 500 in submersibles. I’ve spent more time on and (via my robotic cameras) ‘inside’ Titanic than the ship’s captain did. And I’ve dived to the deepest spot in the world’s oceans, seven miles down in the Challenger Deep.

But compared to some of the cave divers in this book, I feel like an amateur. They may differ in background and personality, but they all share the same rare combination of intelligence and grit. They survive the seeming impossible through an absolute focus on the task. They pit their wit and their stamina against the most fearsome physical environment imaginable. They understand the extreme risk they take diving under thousands of feet of rock, where the only way out is back the way you came in, and where there is zero possibility to simply swim to the surface if something goes wrong with you or your gear.

They manage that risk to its lowest possible value through intelligence, training and meticulous planning. But they can never manage the risk to zero. They accept the risk that remains, what I call the X-factor, because they are driven by the true explorer spirit.

Cave divers are some of the most self-reliant people on the planet. Even if you dive as a team, like Craig and Harry do, you’re still alone on the dive. When squeezing through passages so narrow you can’t wear your air cylinder on your back, with the rock pressing down on your spine and up on your belly, in water so murky you can’t see your hand in front of your dive mask, miles in from the entrance, beyond all possible hope of rescue – you’re on your own. The other guy might only be a few feet away, but he or she can’t help you.

Cave diving is both highly technical and also the most primal human-mind-against-nature challenge that I can imagine.

I was initiated into cave diving by my good friend and co-leader of several of my deep ocean expeditions, Andrew Wight. Andrew was well known in the Australian cave-diving community, and possibly best known for leading an ill-fated expedition in the Nullarbor cave system in which the team became trapped inside by freak flooding and had to explore their way through to a previously unknown exit passage. He convinced me to make a fictional feature film, loosely adapting that story, which became Sanctum. In the process of producing that film, I learned a lot about the techniques, and the hazards, of cave diving. I also had to imagine, and bring to the screen, what it was like to be trapped by miles of solid rock, alone in the darkness with no hope of rescue. So I can extrapolate what it must have been like for those lost boys, in the days before they were found and as they waited to be rescued, and what it was like for the heroic divers who went in after them. Harry and ‘Wighty’ were friends, and hence Harry and I crossed paths on the set of Sanctum and in the Deepsea Challenger factory.

When I was reading Harry and Craig’s story, I was biting my nails during some of the sections where they take us through the rescue dives moment by moment. Even though we all know that it ended well, it’s important to remember that they didn’t know that in the moment. Every decision they made was literally life or death, for those trapped kids, and possibly for themselves.

I was particularly struck by the soul-torturing ethical dilemmas each man faced as medical professionals. No one had ever drugged a child into unconsciousness, put diving gear on them, and then dragged them out through miles of flooded tunnels, including constrictions so small a single diver could barely slither through, blinded by silt, doing it all by feel. It’s one thing to make decisions for yourself, as an explorer and adventurer, quite another to make them for a trusting and innocent child.

There was no precedent to what they were doing, and no guidelines for how it might even be accomplished. They were making it up as they went along, with the eyes of the world upon them. Not only the eyes of a fickle media, but also the eyes of the Thai authorities and the terrified parents. Imagine that dread weight upon their shoulders, as each decision was taken: what drugs to use? what dosages? and how to maintain that level of sedation? Additional injections would have to be administered throughout the multi-hour ordeal of the extraction. The rescue divers might even have to inject these kids through their wetsuits in some dark, flooded passage. They didn’t know if they’d be bringing out corpses by the end of the dive. And if the first died, or the second, would you go on and inject that third kid and try it again? So many unknowns, so many variables. It must have seemed like madness, but at the same time their relentless logic said it was the only answer.

In reading this book you’ll live it, hour by hour, minute by minute, as it was experienced by two divers at the front lines of the rescue. Harry and Craig repeatedly stress how many skilled and heroic divers were involved in the rescue besides themselves – the British cavers who found the boys and helped with the extraction, the Thai Navy Seals who stayed with them in their subterranean prison and kept them healthy and hopeful, and many others.

Before it was finished, the rescue effort involved more than 10,000 people, including over 100 divers, 900 police officers and 2000 soldiers. A hundred government agencies from all over the world participated. But in the end it boiled down to a handful of skilled divers who swam those boys out. This book puts you there, deep inside that flooded cave, experiencing it first hand.

It is an inspirational story of what we humans are capable of when we come together to help others. It chronicles the international outpouring of empathy and effort to save those innocent lost boys. It is also an epic underwater adventure, the stuff of novels and movies, told in a humble, matter of fact way. But this isn’t some Hollywood screenplay – this actually happened.

James Cameron, September 2019

Against All Odds Craig Challen, Richard Harris

The inside account of the breathtaking rescue that captured the world.

Buy now