- Published: 28 May 2024

- ISBN: 9781405953191

- Imprint: Michael Joseph

- Format: Paperback

- Pages: 320

- RRP: $26.99

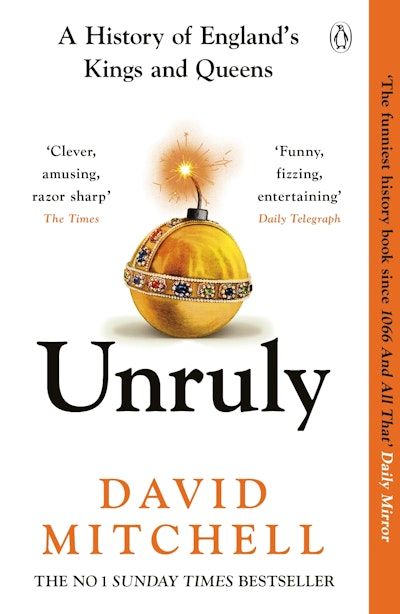

Unruly

A History of England's Kings and Queens

Extract

This sort of thing is typical of Churchill. It’s a big, quirky idea and he was a big believer in ideas. He had a lot of them and he was drawn to other people who had them. Most of us probably think we’re believers in ideas too, but we’re deluding ourselves. Believing in ideas is one of those attributes like libido or skill at driving a car that most people reckon they possess in above-average quantities – but that’s mathematically impossible.

Admit it: ideas can be annoying and frightening and threatening and most of us slightly shudder whenever someone has one. The internet was an idea. So were self-service tills in supermarkets and privatizing water companies and stuffed crusts. Ideas aren’t all lovely vaccines – they can be a right pain. We all like some ideas that have already been had – normal pizza, dishwashers, freedom of speech – but we don’t put much faith in those that are yet to emerge. We generally think that a problem is what it is, and needs to be addressed in one of the established ways that have been handed down for addressing it. And we’re usually right. When a pipe has burst, you need a plumber not a glittering-eyed futurologist saying, ‘What if we could construct a world where we didn’t need water . . . ?’

Churchill was different. He’d give that proponent of water obsolescence a fair hearing and a modest research budget. On Churchill’s watch, Britain was a great power becoming increasingly strapped for resources. For Russia or America, the solution could always be more troops or more money. Britain, on the other hand, was on the look-out for deft ways of keeping up geopolitical appearances, and a clever new idea always held out that hope.

Hence, during the First World War, in the face of the Western Front’s murderous deadlock, Churchill championed the idea of attacking Turkey. I think this was actually quite a sensible plan. The knackered old Ottoman Empire was a far feebler military opponent than Germany, or even Austria-Hungary. Sadly, however, the resultant Gallipoli campaign of 1915 was a fiasco that left Allied dead lying thickly along the Aegean coastline like a macabre khaki pastiche of holidaymaking customs to come. It was more a screw-up of execution than of conception, but it nevertheless shows that thinking outside boxes can sometimes result in thousands of young men getting buried in them.

By 1940, several loop-the-loops later in Churchill’s rollercoaster career, he was hoping this new idea would somehow prevent the surrender of France even if it were to be militarily defeated. If ‘two become one’, as the Spice Girls put it (in a song that weirdly turns out not to be about the proposed Anglo-French merger at all but just about having sex), then both Britain and France would have to be defeated before either of them could be. That was what Churchill reckoned.

The French turned down the offer. Perhaps it felt like a proposed British takeover. That might not have appealed to them at a time when resisting a German takeover was their focus. My suspicion is, though, that they simply didn’t see the point of it. They had no sense that their nationhood was dependent on the mere continuity of political organs. They’d had three monarchies, two empires and three republics in the previous 150 years – they’ve had two more republics since. They knew that the state can be crushed and occupied and yet the country, the nation, some sense of a thing that is France, will continue to exist.

The English feel differently about themselves. Vera Lynn may have sung ‘There’ll always be an England’, but she can’t have been certain or it wouldn’t have been worth claiming. Just as when someone promises ‘You’ll be all right!’, the implication of jeopardy is clear. But what was actually threatening England, as in the geographical entity, the densely populated section of a small island? Nothing. The song was released in 1939, so predates any fears of nuclear Armageddon, and our current concerns about the climate and rising sea levels were decades in the future. Physically, Lynn must have known, England was bound to endure, the ravages of the Blitz notwithstanding. England might be made to suffer pain and indignity, many of its people might die, but of course it would remain, just like the sea and the sky.

So when Lynn or Churchill referred to England, they weren’t just thinking about the place and its people. Their ‘England’ was a different sort of thing from a Frenchman’s ‘France’. To the French, Churchill’s idea was nonsensical. The notion that the structure of a state, a constitution, could be a more effective vessel for Frenchness than the vast land of France was absurd. German soldiers might march all over it, but that didn’t make it Germany – it would remain, whatever happened to it, France.

To Lynn and Churchill, England’s existence was inextricably linked to the continuity of its institutions. And, at this point, it has to be said, when a British statesman said ‘England’, he often meant ‘Britain’. The near eclipse of the ancient kingdom of Scotland in the British establishment’s sense of national continuity is another thing that might have made the French hesitate before agreeing to Churchill’s merger. The UK, the establishment assumption would have been, was primarily England. And England was predominantly not its fields, valleys, lakes, poetry, music, cuisine or folk art, but the pillars of its constitution: its empire, its church, its ancient noble families, its parliament and, first and foremost, its monarchy. For England to always be, those things must always be too.

Monarchy is what England has instead of a sense of identity. The very continuity of English government – the rule of kings morphing into the flawed parliamentary democracy of today – has resulted in our sense of nationhood, patriotism and even culture getting entwined with an institution that, practically speaking, now does little more than provide figureheads.

This has become clearer in the last few years. Britain has been feeling pretty low about itself. Fear, anger and poverty have been on the rise. The only events that have allowed us to pause, even briefly, in the constant mutual recrimination that the situation has aroused have been the Queen’s Platinum Jubilee, then her death and funeral, and then the coronation of a new king.

These were the occasions that brought us together and, albeit with varying levels of irony and cynicism, allowed us to celebrate our existence. We seem to need the trappings of monarchical continuity in order to reflect contentedly upon ourselves, just as we need alcohol in order to socialize. The English have more to fear from republicanism than most – we risk losing our skimpy sense of self.

It seems subtly different with Scotland, Wales, Canada, Australia, New Zealand and the various other places England currently shares its monarchy with. And less subtly different with most other countries, where they’ve had revolutions and changes of constitution lots of times, and learned the largely happy lesson that they didn’t lose their whole identities when they stopped having kings or gave their assemblies new names.

The English tradition of kings and queens has a lot riding on it and a lot to answer for. Its longevity, and the stability that that implies, has resulted in an England that doesn’t have much else uniting it. Simply because the monarchy has never been removed, except for a brief experiment in the middle of the seventeenth century, we’ve never been forced to work out what else we might be other than a kingdom.

What do we stand for really? Freedom and democracy? Tradition and hierarchy? Bad food and sarcasm? Traffic and disappointment? Ships and factories? Rain and jokes? We’ve never agreed on anything and the royal family have long since stopped taking the lead. They just smile and keep it vague. This was the late queen’s greatest talent: being the screen on to which everyone was invited to project their own views.

I don’t really mean this as a criticism. I’m not sure it’s healthy for a state to proclaim a unified sense of self. I used to enjoy feeling slightly contemptuous of the French and American habit of sticking their flags everywhere as if they can’t get over themselves. We didn’t do that in Britain. Then Boris Johnson announced, in his desperation to stoke nationalistic fervour to distract from his government’s manifest failings, that the union jack must now be flown on the country’s every available pole, and that small pleasure was denied me.

The fact is that, when millions of people are involved, any sense of a nation united in its values can only be portrayed by repressing the feelings and views of many. Humans don’t often agree and it achieves nothing to pretend that they do. Genuine consensus is rare and open disagreement beats fake consensus. Whenever politicians mention ‘British values’, it’s only ever to trick us. To flatter us with the thought that we’re all paragons of liberty, fair play, common sense, justice, opportunity or some other concept that virtually no one outside Iran and North Korea would fail to pay lip service to.

Still, as we become less comfortable about our imperial past, and as Scotland and Wales seek solace in their own distinct cultural identities, the majority of Great Britain’s citizens, the English, are left puzzling over what they’re supposed to feel collectively. The ferocious interest that many of us are taking in the rift between Harry and Meghan on the one hand and Charles, Camilla, William and Kate on the other may be a side effect of this. Are we hoping that, in that row, we can find some answers? Is that why, even though it’s just a family quarrel among strangers, we’re drawn to it as if it’s a soap opera made of crack?

We look to the royals because we look to the past and royalty emerged from the past. England’s identity is England’s history. More than with any other nation I can think of, the two concepts seem synonymous. Leaders talk of the future, about becoming a modern, thrusting, caring superpower of enterprise or greenness or science or education – and we nod along. But who really feels that’s what England is?

As I confront my own puzzled sense of national identity, I have reached for the best way of explaining my own people, and people in general, and that’s history. So this book may be about all the kings and queens who ruled England – and it’s mainly kings, the olden days being, among many many many other flaws, extremely sexist – but it’s not really about the past. It’s about history. History the school subject, the hobby, the atmosphere, the wonky drawings of kings, the grist to heritage’s mill-that’s-been-converted-into-a-café, the sense of identity.

History is a very contemporary thing – it’s ours to think about, manipulate, use to win arguments or to justify patriotism, nationalism or group self-loathing, according to taste. In contrast, the past is unknowable. It’s as complicated as the present. It’s an infinity of former nows all as unfathomable as this one. That’s why historians end up specializing in tiny bits of it.

For England, in particular, history is about who we collectively are and how we feel about it. It’s one of the attempted answers to the great human question: what the hell is going on? Most animals don’t ask that question, which is why you can put a massive Ikea next to a field of sheep and they just keep on grazing. Not even twenty minutes of bleats and gestures and questioning looks, they’re just not interested. But a vast amount of human endeavour is an attempt to answer it in different ways: all the sciences and all the humanities. Microscopes, philosophies, expeditions, religions and poems are all having a go.

Of all of those attempted answers, history is the one I reach for first. After all, if you walk into a room and someone’s standing on a table waving a gun and someone else is having a wee in the fireplace and there’s an enormous bowl of trifle in the middle of the floor in which a terrier has drowned and, on the TV, it’s nine minutes into a DVD of One of Our Dinosaurs is Missing, and you ask that great human question, then the best answer is a history. What happened before is the best explanation of what happened next. It’s more pertinent than getting into how dogs evolved or the functioning of the human kidney or the economics of 1970s cinema.

This book, then, is an anecdotal attempted explanation of England, focusing on what I find most interesting. More often than not, that has something to do with a person wearing a sparkly metal hat. If you think that sounds silly then remember: in Britain today, pictures of that hat are everywhere – on stonework, signs, documents and websites. The hat is still doing what the first bossy and brutal man who ever put it on meant it to do: conveying authority and asserting power.

Unruly David Mitchell

A seriously FUNNY, seriously CLEVER history of our early kings and queens by one of our favourite comedians and cultural commentators.

Buy now