- Published: 3 November 2020

- ISBN: 9780143796039

- Imprint: Viking

- Format: Trade Paperback

- Pages: 304

- RRP: $34.99

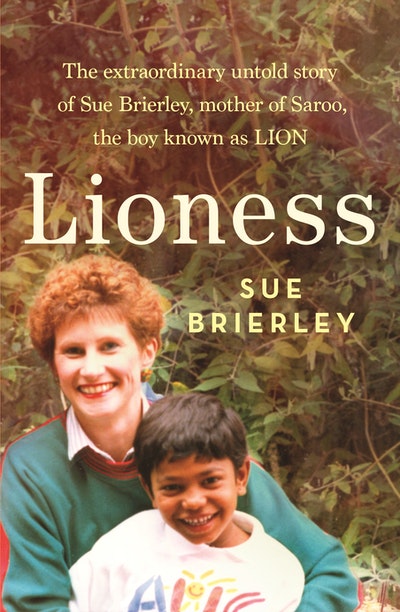

Lioness

The extraordinary untold story of Sue Brierley, mother of Saroo, the boy known as LION

Extract

Saroo’s journey from India to Australia and back again was truly a miracle, given he had become separated from his eldest brother at a train station at Burhanpur and then travelled thousands of kilometres to Kolkata after becoming trapped on a train. It was not until a quarter of a century later, as an Australian adult, that he found his way back home. He would never have found his way back but for the development of an amazing computer program called Google Earth that shows clear, close-up satellite images of landscapes, villages, towns and cities across our entire planet. We will always be grateful to the computer programmers who, through their innovation, unintentionally brought the India of Saroo’s childhood memories to life for him in his secret search so that he could recognise where he had come from and be reunited with his first family.

I am forever grateful that I was also able to meet Saroo’s first mother and hear her powerful words: ‘I give you my son.’ The effect her words had on me was life-changing. In that moment I recalled the true meaning behind the ancient Sanskrit word namaste: not the clichéd end to Western yoga classes, but the greeting used in India that roughly translates as, ‘The divine in me bows to the divine in you.’ A mark of respect and reverence. With her words, Saroo’s first mother had assured me that we were sisters in motherhood, and I truly felt it, just as I had in my childhood vision. My guilt – knowing her loss had created my joy – fell away while we embraced our son in a circle of life. I still remember the touch of her hand gently wiping the tears from my face. I can still feel the sand between my toes, just as Saroo would have felt as a tiny child playing in that very spot where he had lived for the first five years of his life.

Of course, the story of how Saroo came into our family and, just as importantly, why has been a question often asked of us. He has answered much of the ‘how’ in his book, A Long Way Home, also known as Lion after the critically acclaimed movie that depicted his journey, but perhaps I can answer more of the ‘why’ in telling our story of overseas adoption.

I have found the process of writing my own life story, as well as my thoughts on humanity and the direction our world is taking, challenging but strangely cathartic. Most of all I have felt compelled to share my experiences and views of the ‘mother myth’ – society’s notions of the maternal instinct somehow being natural and the result of a biological connection with a child – so that perhaps readers will understand there are different ways of becoming a mother. I feel no loss of ego in revealing my life story, especially the more difficult and painful parts, and I truly give my story with love to all who will read it. This is my truth about how I came to motherhood and what family has meant to me, living my own version of the mother myth with the gifts of my two precious sons, Saroo and Mantosh.

Chapter 1

New homelands

My story has motherhood at its very heart, so perhaps the best place to start is with my mother. Julie Stelnicki, née Holzberger, was lying in a bed in Burnie Hospital in north-western Tasmania, thousands of miles away from her family. The maternity ward was cold and harshly lit, the pungent smell of antiseptic overwhelming.

When I look back on the day of my birth – 14 May 1954 – I think about what a lonely, frightening experience it would have been for my mother, labouring alone on the other side of the world from everybody she loved. She was a young migrant woman whose family had been uprooted from their home in Hungary by the Second World War and scattered across the world – that is, the members of her family who had survived. She could speak very little English and endured the birth process with very little sympathy from the nurses in their stiffly starched uniforms.

The memory of the difficult birth my mother had already experienced with my elder sister, Maria, was still seared strongly in her mind, and the effects of that birth and the doctor’s warning to take special care of her fragile firstborn child would remain with my mother for the rest of her life. There was no comfort for my mother on her second birth, either. The nurses told her to be quiet rather than trying to understand this foreign woman, or even give her a kind word or smile, even though so many of the births in the hospital would have been by migrant or refugee women.

Indeed, even after the birth the midwives continued their intolerant attitude towards my European mother. They scoffed at the name she wanted to give me, as she could not spell it in the English style. ‘Why would you want to call her Suzanne? Susan is much more sensible. And you need to have a second name too.’ And so it was that my mother was overruled and I was given the much more common English name Susan, paired with the middle name Ann. (I would change it to Suzanne, which I always felt was my rightful name, when I married at seventeen.)

The midwives’ attitude paled in comparison to the treatment Julie knew she was to face on her return home with her tiny newborn daughter. Her husband, Josef, my father, would have been at home with six-year-old Maria, but he would have been of no assistance to my mother if he had been allowed in the ward, and indeed was not much help to her for the next three decades of their marriage. Julie knew she was in for a harsh and loveless future with her domineering husband.

In spite of these hardships, I like to think – I hope – that my mother saw my birth as a moment of renewal, a chance to make a new life in a new, young country with her own young family. Although she had inherited the belief from her Catholic faith that motherhood was a natural and necessary next step after marriage, perhaps she viewed it as a chance for her to compensate for the things she lacked in her own early life, and to protect her children no matter what difficulties they faced from within and outside the family home. Maybe she could be a better mother than her own in this new country called Australia.

To be honest, my parents shared little with me about their early lives; in our family, the past was a taboo subject. Most of the questions I asked as I was growing up were met with a stony, suspicious silence, so I soon learnt not to pry, especially with my father. The scant details I do know, however, form the foundations of my early life, the woman I became and the family I was to parent as an adult.

My mother was born on 10 January 1927 in the Hungarian village of Mokra, the youngest of Sidonia and Andreas Holzberger’s fourteen children: eight sons and six daughters. According to my mother, Sidonia was not an affectionate woman. She was very dutiful in her role as a good Catholic wife, but rarely had the time or inclination to create an environment of love and warmth with her huge brood. In turn, my mother found it hard to interact with my sisters and me in a fun, affectionate way and she rarely hugged us, although by the time she was a grandmother, she was far softer and much more relaxed and demonstrative with her grandchildren, as often happens in families.

It was heartbreaking for me to learn later on, through the scraps of information my mother divulged in unguarded moments, of the hardships she endured in a very poor family. From her early years she spent most of her days helping her mother with chores. Given the complicated logistics of preparing meals for sixteen people, tasks such as potato-peeling took hours, at least when the family was lucky enough to have potatoes. My mother’s stories of potato-peeling must have had a significant impact on me and my particular relationship with the humble vegetable because it’s not a favourite, even now. So I say to myself when I am doing the peeling, ‘Make it special,’ because I still try to relate to my mother’s horror of not having enough to eat, a situation that also blighted the early lives of my own sons.

Another of my mother’s responsibilities was moving the family cow around to better pastures throughout the day. She remembered this as being a pleasant task, enabling her to wander quite a distance from Mokra, often into the alps that were not too far away. I can relate to her love of the long walk for the sheer pleasure of being at one with nature and as an escape from domestic drudgery.

My mother was twelve when the Second World War began. In the tumultuous and tragic years ahead she saw most of her brothers conscripted into the Hungarian Army and experienced the trauma of having to flee her village with her family to the relative safety of Germany because Russian troops had invaded Hungary and were marching towards Mokra. Later, two of her beloved brothers, Stephen and Andrew, were killed on the very day the war was declared to be over.

After the war, when Germany was split into two, all of my mother’s family were on the western side except for one of her sisters, Theresa, who was trapped on the eastern side. This separation affected my mother deeply, and unfortunately Theresa was to endure an isolated and difficult life as a farm labourer in East Germany. Mum was only ever able to see her once more, on an overseas trip after German reunification, before Theresa passed away at sixty-seven from thrombosis and an infection after a hip operation. Any type of family separation is tragic, and it seems to have been a recurrent theme in the various generations of my family, including, of course, for my sons.

My mother’s remaining family members were very keen to return to Mokra, but historical circumstances again conspired against them. The borders had been redrawn and their village was now part of Ukraine, so they were warned that if they returned they would be shot in the street in front of their house by the new residents, or marched to Siberia. My grandparents were devastated to realise it would be impossible to return to their previous life but pragmatic enough to accept it was time to form a new allegiance to West Germany and make the best of their life there. All of their surviving children had now grown up and were happy enough about escaping the hardships of village life, trusting they would have a more prosperous future in Germany or in other countries willing to accept refugees such as the USA, Canada, New Zealand and Australia.

It was after the war ended that my mother met her future husband. Josef Stelnicki was tall, dark and handsome, and full of bravado. Apparently he had spent most of the war with the Polish resistance movement, which acted to liberate Poland from German occupation, although my knowledge of his involvement was very much based on fragments that I overheard in hushed conversations between family acquaintances. I never heard a single word from him about his time in the war. I grew curious about his past in my teens because I wanted to try to make sense of the way he acted, but my efforts were in vain. Perhaps there was little sense that could be made of his behaviour anyway. He refused to ever consider a visit back to Poland, and I always found this intriguing. Sometimes I sensed he was frightened of the possibility of being discovered leading a safe existence at the ends of the earth in Tasmania.

My birth certificate claims that Josef was born in Uza Selone, Poland, on 22 April 1922, the only child of farm labourers. In 1927 both his parents caught pneumonia after a rainy overnight trip in the middle of winter, taking a horse-drawn cart of hay to the market for the farmer they worked for. The hay was covered but they were not. My grandmother succumbed to her illness, leaving five-year-old Josef to be raised by his father. After a year Josef’s father took another wife, who resented her stepson and tried to poison him.

Fortunately, Josef ’s grandmother saw what had happened and took him to a doctor, who administered a medicine to make him regurgitate the poison. From that time on he lived with his grandmother. But his life did not become any easier; she was a hard-hearted woman who instilled Josef with harsh values. He grew into an authoritarian man with a grandiose sense of self-importance.

Sidonia, my maternal grandmother, was very impressed by my father when she first met him and pushed my mother into a relationship with him. She thought Josef would provide a ticket out of the difficult situation they found themselves in as refugees in Germany. Sidonia was now without a husband, as my maternal grandfather, Andreas, had died after the war. To further complicate matters, she’d discovered that Andreas had started another family in Canada, where he’d been working in the forests, on and off, since a young age. These years explained the gap in birth dates between children in my mother’s family of fourteen. So when Sidonia heard of Josef’s plan to start a new life with his bride abroad and then bring out widowed Sidonia to join them, she leapt at the chance.

My mother was not so enthusiastic, though; she still carried a torch for her sweetheart from her village, who had left to join the army and with whom she had always yearned for a reunion in Mokra when the war was over. She wanted to stay close to her family and await any news of her sweetheart, so had absolutely no desire to migrate to another part of the world. However, her mother’s entreaties convinced her there was no point staying in Germany when she had a chance for a better life elsewhere, and so after a brief courtship reluctantly she married my father in the city of Salzgitter, in Lower Saxony, on 13 January 1948.

My mother discovered decades later that a terrible wrong had been done by her mother. When she visited one of her surviving brothers in Germany in 1975, he disclosed that Sidonia had been burning the many letters sent to her from her sweetheart. My mother never found out whether he had survived the war or tried to find her in the postwar years. This surely must have been a bitter pill to swallow and would have made it much harder for my mother to bear the terrible, loveless life she ended up experiencing with my father. I find this so very sad to reflect on.

Josef’s overbearing persona was daunting to Julie, a quiet and gentle village girl. The beginning of their marriage was spent in Germany and soon my mother had given birth to my elder sister, Maria, who was a fragile infant after a difficult labour. My father was enthralled by his tiny, beautiful daughter and she brought out an uncharacteristic tenderness in him, but my mother found parenting challenging, especially with little support from her husband. He carried on with his life of pleasures, often socialising away from home and leaving Mum on her own to care for their daughter, whose health was still delicate.

By 1949 my parents had fulfilled all the emigration requirements to leave Germany, via Italy, for a fresh start in Canada, the country where Andreas had started his other family. Some of my mother’s other surviving siblings had also travelled to a new life in Canada and the United States. Living in Germany with no hope of going back to their village was a driving force for leaving behind the many hardships they were enduring.

My mum and dad, carrying tiny Maria in their arms, boarded the immigrant ship the SS Castel Bianco in Naples on 29 November 1949, after a long train trip from Germany, to take the month-long ocean voyage to their new life. The ship was to bear 864 displaced persons from Germany, Hungary, Russia, Ukraine, Latvia, Poland and Romania to their new lives. Many years later a friend sent me the ship’s manifest and I discovered my parents’ and elder sister’s passenger numbers were 721, 722 and 723. I recognised many of the other names on this list as Polish and as family friends who also came to live in Burnie and its surrounds. Many years after that I also found among my mother’s letters a postcard of the ship that she had kept for decades.

Lioness Sue Brierley

A powerful and moving account of adopting the boy who inspired the motion picture LION.

Buy now