- Published: 18 August 2020

- ISBN: 9781760899158

- Imprint: Penguin

- Format: Paperback

- Pages: 272

- RRP: $26.99

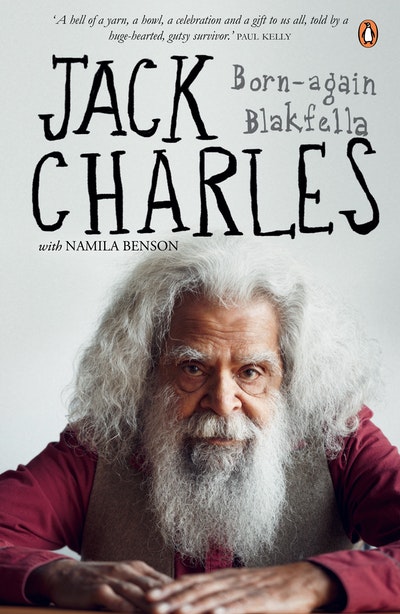

Jack Charles

Born-again Blakfella

Extract

I’m making my way home from the leafy, affluent suburb of Kew in Melbourne’s eastern suburbs. Kew is one of my fave haunts; beautiful and picturesque, even in the still of night. The silhouette of impressive mansions and beautifully manicured hedges looks almost velveteen under the dim moonlight. It’s dark, but I’m expecting dawn to break within a few hours. My general rule of thumb after a burg is to be out of the area before sunrise. I leg it out lickety-split, so that, should the coppers happen to ask locals if they’ve seen anyone dodgy around, they can’t put a face to the crime. Still, it’s the late 1970s and you occasionally encounter a few early risers out and about collecting milk and newspaper deliveries from their front porch.

On this particular morning, I’m a tad late exiting the suburb. I kick into top-notch performance mode and put on my dandified, jolly-good-ol’-chap air, playing the perfectly down-to-earth, nothing-to-see-here, friendly neighbour. It’s easy to do when you’ve been forced to assimilate after years in a white institution. I wander past an old woman collecting her milk and papers, and give her a big flash of the ol’ pearly whites. ‘Good morning,’ I chirp. ‘How are you?’ She greets me with a smile and goes back inside. If the cops later decide to question her – ‘Did you see an Aboriginal man walk past?’ – she’d likely say, ‘Oh, I did see someone, but no, I think he was African-American.’ It makes me laugh that that has actually been reported when people have sighted me. I reckon it’s the wild afro hair that throws them a bit. Too many folks equate Aboriginality with the stereotype of the blakfella silhouette in the distance, balancing on one foot. They don’t think of someone wearing a dark jacket, neatly dressed and walking with dignified purpose through the posh eastern suburbs of Melbourne as though he belonged.

I continue on ‘home’ after the evening’s slog – this morning it’s a hostel. I’m in my mid-thirties and have been homeless, living rough, on and off, for over a decade. I’m also in the throes of a chronic drug addiction. Having dabbled in alcohol, marijuana and recreational drugs since my late teens, I’ve moved on to heroin. This morning, though, it’s morphine and pethidine.

I follow a bottom trail along the Yarra. The sound of the water is soothing and it adds a damp freshness to the air that is familiar, calming and pleasant. I use this trail often as a means to get out of Kew unseen, walking along the bridge. Those of us familiar with the area know to cut through the boat shed, scurry down to the trail below and cross the flattened area to the local footy oval. It can be risky wandering across an open ground because you’re easy to spot and this is the place where the jacks (police) like to do their early morning divvy wagon (police van) rounds. But over time, I’ve become familiar with their schedules.

If I need to stay out of sight, I’ll duck into the women’s toilets – which always smell way better than the men’s filthy urinals. I’ll pull out a book and indulge in my beloved reading. Once the coast is clear, I’ll make a quick exit and head to another of my favourite haunts: Collingwood footy oval. It’s perfect for a bit of shut-eye. You don’t go from the scene of the crime straight to your place. It’s a bit of tip-tap-toe, dashing from one cover to the next, giving a bit of space between destinations.

Today there’s no one around. Before I near the boat shed I pass an outcrop of rocks nearby. Something compels me to glance up and I become aware of a warm glow, a powerful presence before me. I take a slight step back and see an apparition of a blakfella on top of the rocks. Red headband, skinny legs and squatting on one of the rocks, looking down at me. I feel no admonishment or disapproval from this figure. There’s a part of me that is self-conscious initially, but it feels like somehow or other in this moment there is something trying to bridge the gap of my denied cultural history, to set me back on track. Others might find it spooky, hair-raising stuff, but I’m not frightened.

There is no verbal communication between us, just an unspoken understanding that extends well beyond the limitation of words. Perhaps he’s an embodiment of someone who has survived the Frontier Wars and massacres. Or maybe an ancestor keeping ‘blak watch’ over me. Either way, the vision I experience that night gives me clarity and purpose. It guides me to return to my roots, to stand tall and be proudly, unapologetically, Aboriginal.

But then I am, after all, stuffed to the gills on drugs, so I continue on my route to seek sanctuary at the hostel in Fitzroy.

Following a hearty breakfast and good cheer I surreptitiously count my ill-gotten gains, then head out to connect with one of my dealers. A routine that is tiresome and compelling, with a repetitiveness draining, at every turn, my soul.

Jack Charles Jack Charles

Jack Charles has worn many hats throughout his life: actor, cat burglar, musician, heroin addict, activist, even Senior Victorian Australian of the Year. But the title he’s most proud to claim is that of Aboriginal Elder.

Buy now