- Published: 30 March 2021

- ISBN: 9780143796398

- Imprint: Viking

- Format: Trade Paperback

- Pages: 272

- RRP: $34.99

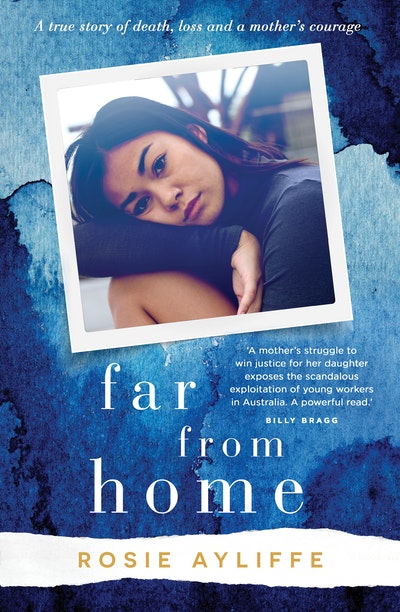

Far from Home

A true story of death, loss and a mother’s courage

Extract

From her early years we’d made a few trips together on Rough Guide research assignments to destinations in Europe. One of my favourites was to France, just after we’d moved to Derbyshire, when we stayed in Sine’s family gîte in the Haute-Vienne for a week, exploring this beautiful region and sampling its local produce. The journey there had been fraught, as we’d moved into our new house in Hazelwood the day before, but I’d promised her a holiday and I was committed to always keeping promises to Mia. So we abandoned the unpacked house, jumped into my small car with luggage and a couple of bicycles, and headed for the ferry.

While there we visited the incredible testament to the Nazi occupation of France, the village of Oradour-sur-Glane. A crumbling shell of a ruined village, it was preserved as a memorial to the French resistance by Charles de Gaulle. The accompanying documentation and film, along with some quite grisly remains, may have been stark viewing for most seven-year-olds, but Mia was absolutely fascinated by the whole experience. I think I realised then that she was a true traveller, in the sense that she was, as the Turks say, uyanik: she was awake and travelled with her eyes wide open, absorbing knowledge and trying to grasp the history and culture of a place. We had a lot of fun on that trip with the help of a friendly local and a fishing rod we bought for a few francs in a local supermarket. Much to Mia’s delight, we even managed to catch a little fish (which we then threw back in).

I also really enjoyed showing her Turkey, which we visited together a couple of times. When she was twelve, we stayed next to a beach in a tree house. (Mia had always wanted us to build one together, but we didn’t have a tree big enough in our garden at Hazelwood.) It was a magical time where we walked up into the mountains to see the geothermal Chimaera at Phaselis, and visited the nearby ruins of the city of Olympos, actually just a short walk up the beach. We snorkelled in the magical azure bay, gathered a huge collection of seashells, and made friends with locals, including a couple who took us up into the mountains to a lovely wooden restaurant which seemed to cling to the hillside in a somewhat precarious manner.

Of course, Mia’s life as a traveller started before her first birthday, when I made the research trip to Turkey with my friend Rachel to update the Rough Guide. One of the many small boutique hotels we stayed in on that trip was in the resort town of Kas. One morning I had to make a call to the Rough Guide head office from reception, so they found out I was a travel writer and were particularly attentive as a consequence. Realising that the adults could probably benefit from some baby-free time they offered to keep watch over Mia while she slept and Rachel and I went out. She had retained her baby form of sleeping soundly from feed to feed so I was confident that after putting her on the breast at 8 pm she would be out for the count for three hours or more. The staff lent us a mobile phone (a novelty to me in those days) and we only went to the restaurant two doors away for the time it took to bolt a meal, but even so I remember being quite panicky at having left Mia.

Years later, after Mia’s death, I listened to Kate McCann’s account of the night they lost Madeleine, and thought back to our time in Kas. At first I’d felt quite judgemental of the McCanns for their error in judgement in leaving the children for the length of time they did, but I now wonder which of us can cast the first stone? And I realise that while losing your child is one thing, living with the guilt of having taken a risk like that? It’s beyond tragic and I have to admire the way the McCanns have stayed true to Madeleine and never given up on her.

We made other trips throughout Mia’s childhood, sometimes using a house swap organisation to travel around the UK. These were proper adventures, where we’d set off as soon as school finished on a Friday evening and head out of town, arriving in the middle of nowhere and then trying to find keys, lights and other means of survival in a strange house. It was on one of these trips when I swapped our ground-floor flat in a busy London street for a remote cottage in the beautiful Hope Valley in Derbyshire, that I started to think about moving out of London. To my mind, these people had everything: a tiny cottage in a thickly wooded valley cut deep into the Derbyshire Peak District, with a stream running past their door and a three-minute walk to the station for trains transporting them to work in Sheffield every twenty minutes or so.

Mia had also made trips abroad with her father, who was working as a roadie for bands travelling all over Europe. She visited a number of countries: France, the Netherlands, Greece, but her favourite by far was Italy, which she fell completely in love with at first sight. She really wanted to settle there from a young age. One of the stories she came back with was that her dad was friends with Joss Stone! I asked what on earth she meant, having a hazy idea of who the famous singer was, and Mia produced a photograph of the two of them together. On another occasion she said she’d been looked after by band members of Goldfrapp while Howard had been working. It wasn’t exactly the high life, but she was getting a real taste for travel and adventure.

As she grew old enough to travel independently, Mia also made trips abroad with her friends and their families, once to a villa located in the Tuscan mountains near Pisa and also to Amsterdam.

I love a story I was told about Mia in Florence when she was seventeen. She was there with some of her friends, including a girl called Lydia and her parents – Esther, a glassware designer and her husband Paul, the owner of our local cinema. Esther told me that Mia had been crossing the road and was standing at a traffic island in shorts and a crop top. As she did so she turned with one hand on her hip, perusing the traffic as she waited to cross. Traffic chaos ensued, as cars screeched to a halt and Italian motorists started honking their horns and calling to Mia! Esther was highly amused at the level of attention Mia received, which was out of proportion to anything attracted by the other girls in the party, but she did have a certain poise which singled her out even then.

From these early forays, Mia saw travelling as the ultimate adventure. She started working evenings and weekends in cafes and bars, saving money for her travels.

*

By the time Mia was nearing the end of secondary school, she was struggling. She realised it took her far longer to get anything on paper than any of her peers. It’s the only time I ever saw her close to despair. She was a practical soul, outgoing, sweet natured and with great people skills, a natural on stage and fun to be around. But academic she wasn’t. I felt as she did, that she needed to get out in the world and try a few different kinds of employment to establish exactly what she wanted in life. I had a feeling she would probably go to university as a mature student, which was entirely feasible, but I was happy that she had completed a childcare course to level three, which was what was required to study at university, so a gap year seemed like a suitable option.

Mia and her friends, and many of mine, talked to her endlessly about places she should visit when she travelled and what to do when she got there. Gradually a year-long trip began to take form. As she planned her itinerary she asked me about places I thought she should visit, and I think I was responsible for some of her choices. Turkey, Morocco and India were all favourites of mine.

The inclusion of Australia was never my idea. It hadn’t ever been on my bucket list, probably because I knew very little about it. The word always conjured up images of red earth, vast empty spaces, ocean rollers and a carefree attitude to life. I was warned that Mia might encounter racism, and at first I was quite troubled at the idea of Mia travelling there.

However, my cousin Henry’s dear Singaporean wife, Bee Lin, told me that she’d only had positive experiences in Brisbane, and the sole racist comment she’d received had been while in Melbourne. This put my mind at rest. Mia’s older half-sister, Nicola, had spent a couple of years in Australia working for Qantas, and loved it so much she was struggling on her return to London. Other friends had settled there and were working in good jobs. They talked about the sun, sea and surf, but also great rates of pay and endless opportunities for young people.

So the route took shape, and Mia began organising her journey, cross-referencing endlessly with guide books lent to her by friends, and internet research. She had decided to book her tickets one by one instead of a single round-trip ticket, because she knew it was cheaper to do it like that. She planned and plotted, purchasing her visas and making sure she had all the right vaccines. I was proud of her for being so organised and together about it all. At the age of twenty, she seemed to have covered all bases, and she was good to go by late 2015.

Mia’s original plan had been to travel with her cousin Aoife, until it materialised that Aoife’s idea of a holiday was to stay in a five-star hotel with wheeled suitcases and preferably a boyfriend in tow, so their plan soon fell apart! Mia started to make other arrangements with her ex-boyfriend Elliot but he had already done his travelling and decided he wanted to establish a career in the music business, so solo travel became her default position, and frankly she was terrified. Much as she wanted to go on an adventure, she was leaving so much behind in terms of family and friendships that her nerves were mounting as she spent sleepless nights wondering whether she was capable of making this trip alone.

Eventually she voiced her concerns to me in a soul-searching conversation that I will never forget. She asked me whether or not I thought she could do it. I thought about it, wanting to give her an honest answer, and replied that, yes, I believed she did have the necessary skills to make a success of a big trip like this. I pointed out that she was lively and vivacious, and therefore people would want to spend time with her. I told her that travellers tended to hang out together and that she would be in demand as a companion because she was fun to be with. I reminded her that I was always there for her, and if she needed me I could help her out either financially or in person. It never occurred to me that she would be dead before I realised she was in trouble. Knowing what I now know, would I have answered differently? Of course I would, but I suspect she would have gone anyway, without my consent, and we would not have maintained the contact we did up until that awful night in Queensland.

Mia asked me what advice I would give her about travelling generally and in Muslim countries in particular, and I told her to observe how the locals behaved and to follow their customs. I pointed out that it would be best to cover her shoulders and legs when out and about, and to carry a scarf so that she could always cover her head. I told her to watch the manners of the women, and not to engage in eye contact too much with men as they might consider it flirtatious. I also advised her to make friends with other travellers, and to go about in a group, preferably with men around so she appeared to be protected.

As it turned out, her first trip, to Turkey, was almost cancelled because of a mini coup attempt in July 2016. Stewart, Mia and I watched the action unfolding on TV and it was frightening for all of us. It made me think twice about whether Mia should visit Turkey at all. As it happened, a kind of stalemate was re-established quickly – it turned out not to have been a coup so much as a minor infraction on the part of the followers of an exiled cleric – so the last-minute plan was for Mia to depart as scheduled, but to stay with friends of mine. As the day for Mia’s departure approached she became more and more irritable, partly I’m sure because of nerves, but also because we had recently moved into a house in the nearby village of Cromford that Stewart and I were renovating, and everything was either 1980s retro decor or covered in rubble and dust. At first she found this hilarious, and went into every room taking photos for a social media post of all the dreadful materials on the walls and floors and the hideous fixtures, including tiger- and zebra-striped carpets, clashing florals and a frankly quite disgusting bathroom suite which was the colour of rotting eggplants.

When she could make time, she helped out too, and Stewart was particularly impressed when she climbed a ladder and helped us paint the front of the house. She then asked how often this task needed to be performed.

‘Once every ten years or so,’ was Stewart’s reply.

‘Okay, could you make sure you do it again before you die then, please?’

Stewart recounted this to me later and we laughed at this typical example of my daughter’s cheekiness.

There was another funny moment when she arrived home a few days after we’d moved, walked into the kitchen and started telling us in animated fashion about an incident she’d just encountered in the village. She’d witnessed a car accident, and had helped out at the scene by talking to the victims and calling the emergency services. She was incredibly proud that she’d kept her nerve and been useful, and that the family had hugged and thanked her when the ambulance arrived for an injured party. The story was fifteen minutes at least in the telling, and it was only when she paused for breath that she said, ‘Oh! The wall’s gone!’ Stewart had knocked a partition wall down between the kitchen and dining room just minutes before she’d arrived and we were both standing on the pile of rubble.

One evening, Mia’s rising fear about embarking on her journey led to irritation, culminating in her screaming at me that she hated this house and never wanted to see it again. (I think I’d probably had the temerity to ask her to pack her belongings in preparation for the redecoration we were planning when she was away.) We both took some deep breaths and I hugged her before she packed a bag and left to go and stay with her friend Ro.

I’d had a rule since she was little that we would never part on bad terms in case something happened to one of us, so I called her and suggested we meet up and go for a final meal together, which we did, just to make sure we were parting on good terms. Mia returned home two days later and together we packed the rucksack I’d purchased for her trip.

Our local railway station is incredibly picturesque and I’ve always found it a peaceful place to hang out while waiting for a train – especially in summer, when the lovely villa-style waiting room with its mullioned windows (featured on an Oasis album cover) is framed by meadowsweet and willowherb that provides a feeding ground for lazy bees. I had taken Mia there many times over the previous few years. In 2009, when she was fourteen, a body was found in the boot of a taxi in the charming little courtyard out front. Because of this, Mia never liked to wait there alone, so I had seen her off from the platform countless times when she made trips around the country or just to take the train into Derby for a day of shopping.

Driving her to the station this time felt a little different, because this was a long journey. But I assumed we’d see each other within the next twelve months, even if it meant Stewart and me flying out to wherever she was for an extended vacation. Little did I suspect this would be the last goodbye, the last hug, and the last time I would stand and wave a train carrying my beloved daughter into the distance.

I repeated the words I used to say to her when she was little, ‘Love you all around the world and back again, baby girl!’ and made her promise to stay in touch and post lots of photos on social media. And then she was gone. The last goodbye.

Far from Home Rosie Ayliffe

A mother’s story of the death of her daughter and the appalling hidden dangers of working conditions on Australian farms.

Buy now