- Published: 2 July 2019

- ISBN: 9780143784395

- Imprint: Viking

- Format: Trade Paperback

- Pages: 336

- RRP: $34.99

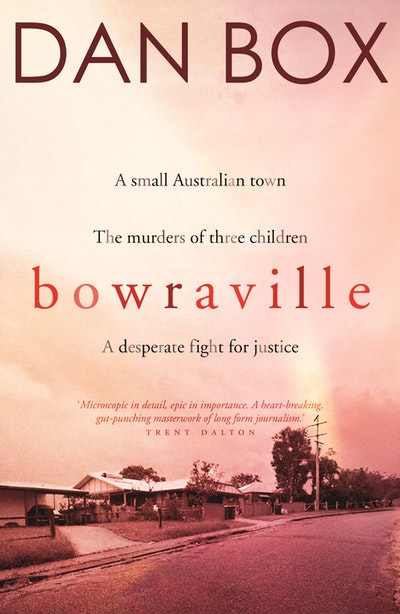

Bowraville

Extract

Sunday, 16 September 1990

It was only three days after Colleen had gone missing that anybody told her mother, Muriel Craig, and the news made no sense to her. No sense to her at all. They told her Colleen had been at a party. On the Mission in Bowraville. The party was at Fred’s place; opposite the Tree of Knowledge. The house at number 4, on Cemetery Road.

Muriel had driven down that morning from her home in Sawtell, less than an hour from Bowraville, just further up the coast. When she went to the Bowraville police station, she couldn’t get an answer to her knocking. Maybe it was shut up for the Sunday. She tried again on Monday, climbing High Street to the hilltop, walking through the gate in the white picket fence outside the neat, Federation building and this time, finding the door open, walking in, out of the sunlight, and ringing the bell on the counter inside. The policeman in his blue uniform looked up and saw her standing there, but took his time to answer. Muriel told him that Colleen was missing. Her daughter was sixteen, she said.

‘How long has she been missing for?’ the policeman asked her.

‘Well, they said she was missing the Thursday night and it’s Monday.’

Muriel showed the man a photograph: Colleen looking confident and beautiful, with red lips just about to smile.

‘This is your daughter?’ he asked her, doubtful. ‘She doesn’t look Aboriginal.’ Colleen had pale brown skin – their family had some white blood in it. The policeman didn’t take a statement. He filled out some paperwork. Maybe he told her Colleen had gone walkabout – Muriel isn’t certain. It’s been so long since it happened and it’s so hard to remember, what with the fear and the emotion.

Muriel said nothing. She couldn’t backchat the police.

It seemed they were not going to help her. Instead, Muriel went home, gathered up her remaining, younger children and moved the family to Bowraville, a small town of something like a thousand people that nestled in a loop of the green Nambucca River on the mid-north coast of New South Wales. There she spent her days driving up and down the Mission, which was just the eight brown-brick houses built along one side of the long stretch of Cemetery Road, pleading or demanding that people tell her if they had seen her daughter. But people only told her fragments. Some said that they’d seen Colleen drinking at the party. Some said they’d seen her outside, where the music and the people had spilled out that night across the road. But the times and names and details were all different. Muriel had to fit these broken pieces back together into a whole.

Michelle Flanders, who got to the party around 8.30 p.m. after finishing her work at the play centre on the Mission, said she found her boyfriend drinking and singing with about eight other boys when she arrived. The drinking had started early but he got up when he saw her and the two of them walked outside number 4, through the wire gate and across the pitted bitumen to where Colleen was sitting underneath the spreading white mahogany they called the Tree of Knowledge. She was one of those gathered round the fire with Kelly Jarrett, who was celebrating her eighteenth birthday. James Hide was there with them and some others who Michelle could not remember. The boys were smoking yarndi, or marijuana, while the girls were drinking Passion Pop. When the couple arrived, James handed them a stubbie but Michelle’s boyfriend spat it out and told him, ‘That’s not beer.’

It smelled like bourbon, Michelle thought.

For Muriel, the story got more confusing. The party was at the home of Fred Buchanan, who was Colleen’s cousin. Fred later remembered that he’d been drinking all day in the house, sitting in his bedroom with the other blokes before crashing out at about 8 p.m. Colleen had come late to the party and hadn’t stayed there. She was wearing a white jumper with a blue-and-red band and light blue jeans cut short to the knee, he remembered.

Fred said Colleen had walked into the bedroom, holding a bottle of Passion Pop and talking about catching the train to Goodooga in the morning. Goodooga was out west, more than a day’s journey from Bowraville via Sydney. After the party, he heard that a white Holden Commodore had come along outside and someone from inside had called out, ‘Uncle George, where are you going?’ It sounded like it had been Colleen talking, someone told him, though Fred didn’t see or hear it for himself. He blacked out and woke up something like twelve hours later, long after the early morning train for Goodooga had gone.

Martin George Greenup was drinking in the lounge room at the party with James Hide, who was the only white man among the crowd of blackfellas, and remembered that he overheard James saying, ‘Come on babe, Colleen, I want to see you tonight.’ Colleen got upset, walked outside the house, and sat on the front step. She was a pretty girl, with dark, curling hair and an easy smile. She looked like her mother, Muriel.

Sometime around two or three in the morning, after the other boys had finished drinking and crashed out, Martin said that he had left the party and seen a white Commodore parked outside up the road, facing towards the cemetery. Colleen, who was in the front seat, waved and sung out, ‘See ya later, Uncle Martin.’

‘See ya later, Col,’ he told her.

Or maybe Colleen was sitting in the back seat and yelled out ‘How you going, Uncle George?’ It was hard to remember. Anyway, as he was walking away from the party, the Commodore drove past him, heading into Bowraville.

Muriel kept searching for her daughter, trying to make sense of all these different versions, but what people were saying wasn’t straightforward or it changed with each telling or what one person said was contradicted by another. One of Colleen’s cousins said he’d seen her two days after the party, talking about the footy knockout tournament she was due to go to. Kelly Jarrett, whose birthday party it had been that night, told Muriel that she last saw Colleen outside at the party. The two of them had gone over to Fred’s house and stayed there drinking. At about 11.30 p.m. Colleen had come over to where Kelly was standing by the fire. But after that, she hadn’t seen her.

As the weather got hotter ahead of the coming summer, Muriel found that her suspicions worsened. She was a proud lady. Defiant, you might call her. She’d grown up on the Mission and many of the people living there were family. But it seemed they could not, or they would not, tell her what happened to her daughter. Their versions were all different. They couldn’t all be true.

The last time that her mother saw her, Colleen had given her a kiss and said, ‘Mum, I’ll see you Sunday.’ That was on the Monday, 10 September. Muriel had not worried about letting her daughter travel down to Bowraville. Colleen would do what she wanted. A few months earlier, in March, she’d got sick of school and left it behind her. Yes, Colleen drank a bit and smoked a little yarndi, but she’d been to Bowraville before, staying there with family, and she’d also spent time living in Macksville, the next town down the river. But each time she went away, when Colleen asked her, Muriel had picked her up and they’d gone home together to Sawtell.

After school, or at the weekends, Muriel’s other children went out with her around Bowraville, looking for their sister. They didn’t fully understand her absence. The youngest, Lucas, who was only eight or thereabouts, watched his mum running around and saw that she was panicking and hurt. But they were only children. Lucas felt guilty there was nothing they could do.

The days turned into weeks and Muriel’s suspicion expanded. If no one was telling her what really happened to her daughter, maybe they were hiding what they knew. She started to look at people differently, asking herself if they were acting smart. She needed to find a common thread, something she could follow, which ran through all the various accounts. Something that would lead her to her daughter. Like the white Commodore, perhaps, which people told her Colleen had been sitting in that night.

Jason Buchanan had been at the party and said he saw the car parked up outside the house at about 11 or 11.30 p.m. Beyond it, the fire was burning across the road by the Tree of Knowledge, where he recalled James and another fellow had two crates of VB. Jason went to have a drink and Colleen joined them. Jason said he heard a woman laughing in the Commodore and recognised the voice as Maxine Jarrett’s. He last saw Colleen at about 12 a.m.

Maxine Jarrett said she’d been drinking at a nightclub in Nambucca Heads, about 20 kilometres from Bowraville until sometime after 1 a.m., when she met a bloke who said he had a car and offered to drive her home. When they arrived at Cemetery Road, she didn’t see anybody underneath the Tree of Knowledge. They were the only people in the Commodore, she said, just her and the driver.

Now all Muriel had was more suspicion and confusion. She just wanted to find the last person who had seen her daughter.

Patricia Stadhams said that she had seen her. Patricia had been walking along the Mission shortly after 12 a.m. on the night of the party. She had seen Colleen outside the house next door to the party. Kelly Jarrett had been across the road, underneath the old mahogany and sung out, ‘Where you going?’

‘I’m just going round here,’ Colleen answered, but Patricia did not see where Colleen went.

It was dark out there, without streetlights. Patricia said that she passed James on the footpath. She saw a white Commodore drive past her and stop a little further up the road.

Later, when the police interviewed her, Patricia said that Colleen wasn’t on the footpath, but heading down a side street beside one of the other houses on the Mission, the next-door one to where the party was that night. That was the same way James was walking, said Patricia.

Years later, Patricia’s story changed again.

Interviewed by detectives seven years after Colleen’s disappearance, Patricia remembered seeing another car, a red Chrysler Galant belonging to James’s mother, parked in the driveway at the back of the Mission. She’d stopped and watched Colleen walking down the street beside the house towards where the car was parked, and watched James go through the gate and down the other side of the same building.

‘He looked suspicious so I stood there and watched him,’ Patricia told an inquest in 2004, fourteen years after the teenager went missing. She watched both James and Colleen walk away from her, towards where the car was waiting. The next day, both Colleen and the red Galant were gone.

Bowraville Dan Box

Winner of the Ned Kelly Award for True Crime.From the creator of the Walkley Award-winning podcast comes the story of a small Australian town, the murders of three children and a desperate fight for justice.

Buy now