- Published: 30 July 2018

- ISBN: 9780143783169

- Imprint: Viking

- Format: Trade Paperback

- Pages: 272

- RRP: $34.99

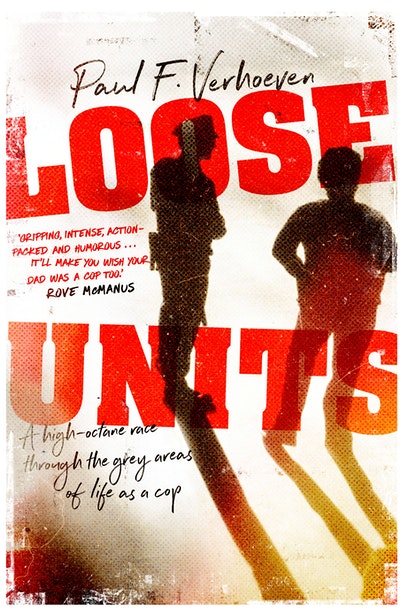

Loose Units

Extract

Prologue

I was seven years old when I saw my first dead body.

It took me a moment to register what I was looking at. I distinctly remember feeling very sick, then very cold all over. The body was a woman’s. Her eyes were still open, her pale hand was extended, and one of her legs was twisted under her body at a strange angle. Her blouse was torn, and there was a lot of blood.

At seven I was a small, skinny, generally cheerful kid. On this particular night I strayed from a dinner party my parents were throwing to go spelunking in a large walk-in closet at the back of our home. Before you get the wrong impression, there wasn’t a body in the closet itself, this isn’t going to be one of those stories. I’d simply reached an age where the length of my limbs, when splayed outwards, perfectly corresponded with the width of the closet. And given that I had unusually large feet and hands, and given that the walls had a certain degree of stick to them, and given that our ceilings were unreasonably high, it wasn’t uncommon for me to wedge my arms outwards, Samson-style, and then shimmy up the walls until I was flush with the closet’s ceiling.

The first time my parents came looking for me in there, with me pinned against the roof, and them standing directly underneath me with a puzzled innocence, I felt a sense of intense elation. I had suckers for hands and nothing could bring me down.

This giddy triumph was marred slightly after they left, when the sweat of adrenaline that had been collecting on my palms broke the bond between me and the walls, sending me plummeting, like a freshly felled Hans Gruber, down, down, down. And right onto a stack of boxes.

Though the option of a full ceiling wedge remained attractive, on this night it was these boxes I instead decided to dive headlong into, both figuratively and literally. The dinner party continued in the living room, with my parents making loud, muffled jokes. I’d brought a small flashlight with me, wanting to keep my presence covert. Even then I liked to imbue everything I did with a sense of needless intrigue. And the second I pulled the lid of the first box away, my flashlight beam fell upon a large, glossy black-and-white photo of a crime scene. It was of a woman’s body. I took a moment to process what I was seeing. The body was upsetting, and I quickly shoved it away, not wanting to stare death in the face. There, I thought, I did it. The four-second rule at work.

But beneath the first photo was another. This one . . . this one had something wrong with it. There was a mass of blood in the centre of a room. Burnt fragments of hair and skin clung to the floorboards. I could see the feet of someone standing in the corner of the photo, presumably a police officer. Wordlessly I replaced the lid, snuck back to bed, turned off the lights and eventually drifted into unconsciousness.

My parents informed me the next morning that I’d been screaming in my sleep all night.

I didn’t tell them what I’d seen.

The picture of the body bothered me, true. But the second picture seized me with a kind of existential dread. Because I didn’t get a great look at it, and because I was coursing with adrenaline and looking at it in a poorly lit closet, it began to evolve. The photo was vague enough, and the memory of it hazy enough, for my mind to fill in the blanks with nightmarish details. Suddenly, every blank space, every spare corner of my growing mind was populated with blood, fear and death, and I began having night terrors on a regular basis. The photos weren’t even that full-on, but my brain hadn’t been exposed to anything violent or graphic up until this point; it was like an Amish youth on Rumspringa, one minute weaving baskets and whistling to itself, the next, doing ice in a wheelie bin. It was a violent gear-shift, and it completely knocked me off course.

When I was in my early teens, I relented and let my parents send me to a child shrink, to try to figure out why I couldn’t stop screaming in my sleep. The shrink couldn’t help, and I just accepted the now recurring dream as an immutable object, folding it into the architecture of my life. Which was totally fine, until as an adult I started a relationship with a woman who told me the dreams had to go, or she would. Snoring was one thing; screaming ‘WHAT DOES THE BURN MEAN? WHY IS THE FLOOR BURNED? WHY IS THERE SO MUCH BLOOD!’ was, evidently, another.

Perhaps those dreams are why I’ve ended up the way I have. I’m in my mid-thirties and I review video games for a living. I ended up studying film at uni and doing a lot of bad theatre, spent years as a presenter on Triple J, and have pretty much bounced between every weird artsy calling you can think of. Which is all well and good . . . but I mean, come on. Look at my dad. Hero cop.

And he was a hero cop – certainly to all the people he helped, the officers who ran alongside him, and to me, who sat there building Lego aberrations on the shag-pile carpet as he came home every day, resplendent in his uniform.

But the dreams have come back, and I’m thirty-five, and I’m looking at the genteel hipster fop I’ve become, and then I get this package in the mail. And it’s full of photos of me as a baby, and I’m being held by my dad, unbelievably young, in his police uniform. Mum and Dad have decided to move overseas and in a newfound Zen-like purge are getting rid of keepsakes. So Mum bundled up sheaves of photos yellowed with age and sent them to me, which I pore over slowly in my office. And then, everything hits me. Why didn’t I end up like him? Why couldn’t I have adventures like he did? Why did I turn out so soft?

That photo.

It was that fucking photo.

So I call Dad and tell him we need to get to the bottom of this, once and for all – the case of why the apple fell so far from the tree. (Actually, that implies that I pursued a life of crime; it would be fairer to say that he became a man of action, whereas I avoided action at every turn.)

I needed him to break down why I hadn’t turned out like him, and why I seemed built to baulk at the cruel truths of life, whereas he was apparently wired to face them head on, and without a whiff of retching. Dad and his partner, Julian – his best friend and the guy I called Uncle while growing up – were heroes to me. They ran towards conflict and action together. I worshipped them both. Why, then, did I struggle so much with conflict? Why did I enjoy the idea of adventure, but come over all reticent when the time came to actually charge at something head on? Why did I view everything through the prism of niche nerd references? Had something not been passed down from Dad to me during my birth? Had something been lost in translation? Did my paltry ‘adventures’ come anywhere close to his?

So I fill Dad in on my grievances, and after a pause, he asks if they’d wasted their money on the shrink. I inform him, yes, they most certainly had. The dreams were back. And when I confess how bothered I am that I’d not been able to bolt towards conflict and save lives, he sighs. Appalled I’d not come to him years before, he proposes something: saturation. He offers to share some of the darkest, most tangled, horrifying and strange stories I’ve ever heard, in the hope that they’ll not just make the dream seem like a whisper by comparison, but so that I might understand why a photo – and that photo in particular – might not be so bad, after all. He tells me to trust him.

So that’s exactly what I do.

My folks live in Beacon Hill, tucked away on the northern beaches. I hadn’t been back in years, and had forgotten how dizzyingly weird the geography is there; it’s practically Jurassic. Nestled in what is effectively a valley, surrounded by byzantine networks of architectural oddities, my parents’ place hugs the hillside, squat, dark and legitimately mysterious. Everything there has a sense memory attached to it. That carpet? I threw up on that carpet. That windchime? I taped it once and worked the audio into a mixtape for a friend who has a pathological fear of windchimes. Once, halfway through listening, she almost crashed her car. Memories bubble up as I head around the side of the house, laptop and microphone in hand.

Mum hears my approach and runs to greet me. Mum is a brilliantly sunny woman, and she practically bounces ahead of me, yelling ‘John! John!’

Dad yells back, sounding cheerful. I get a pat on the back from Mum, and she trots up to the kitchen. I head downstairs.

Picture a study: mahogany, leather, a faint fug of cigar smoke, and light perforated by venetian blinds. Fill the room with bookshelves, and fill those shelves with an inordinate number of Clive Cussler novels. Now, put my father on a leather armchair in the centre of the room, flanked by the same boxes I crash-landed on decades earlier, their lids still battered from the impact. The room has floorboards, with antique rugs laid over one another clumsily, and there’s a window open. Dad always leaves a window open.

Now picture my dad, John. Tall, greying, stylish. He’s a hair over six feet tall, broad shouldered, in his late fifties, calm and collected. And he maintains this air of cool right up until the moment I enter the room.

It is now that I clock his new reading glasses, which magnify his eyes to such cartoonish levels that I have to sit down on account of the laughter. Once I calm down, Dad pours me a glass of water and asks me where I want to begin.

Loose Units Paul F. Verhoeven

Part father-son story, part true crime, Loose Units is a race through the underbelly of policing as ex-cop John Verhoeven tells all to his son Paul about the crimes, the characters and the pitch-black humour.

Buy now