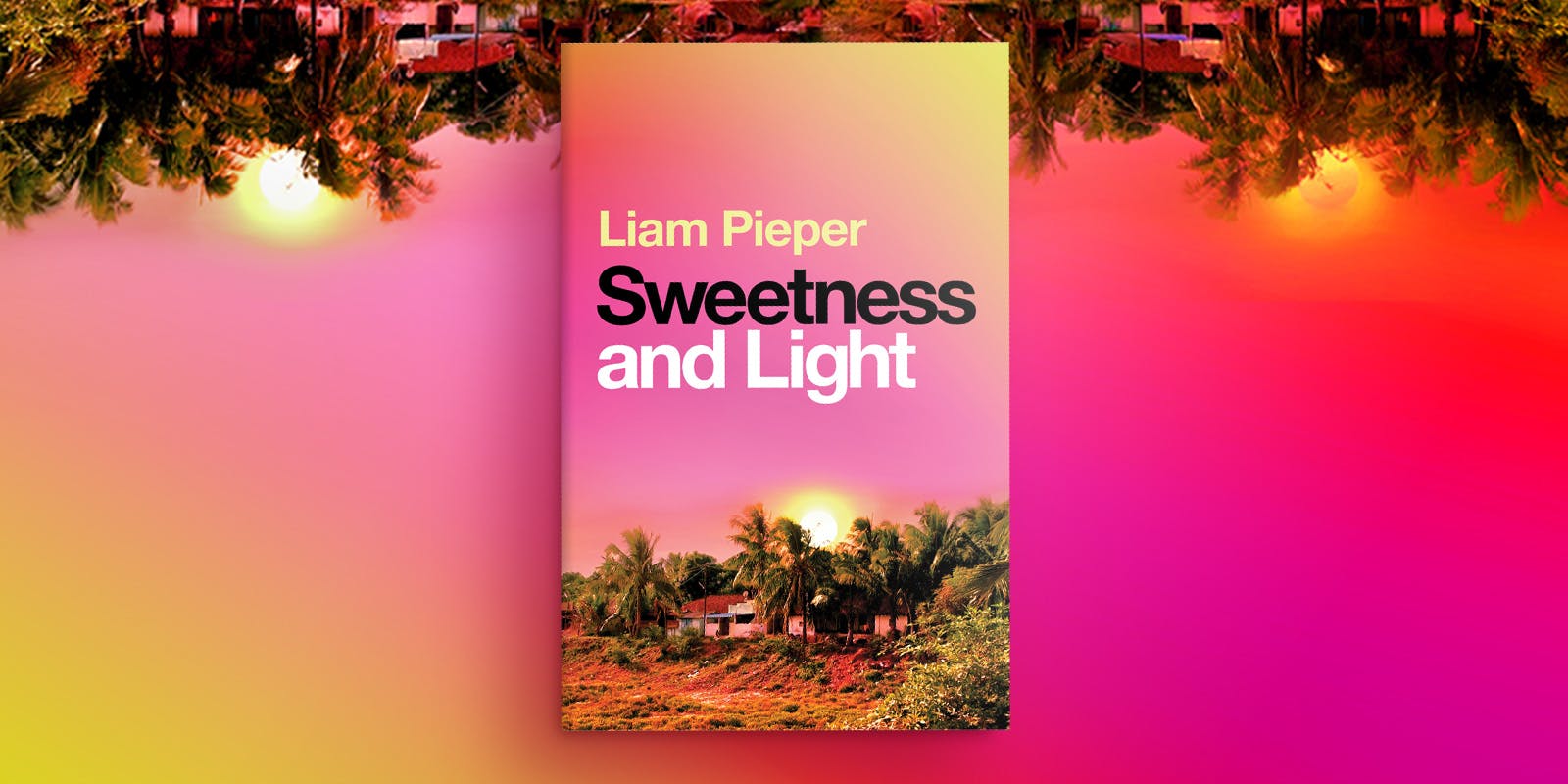

Liam Pieper reflects on subverting the self-actualisation narrative, in Sweetness and Light.

I started work on Sweetness and Light in 2015, on residency in rural Karnataka, about 20 kilometres outside of Bengaluru, right in the heart of India. Most of the other writers in residence were from India – some from small towns, some from cities of 20 million people. Academies, poets, translators and journalists, all of wildly different temperament, drawn together only by the shared love of the written word, and a common burning question: what was the deal with Shantaram?

For those who haven’t had the pleasure, Shantaram is the international bestseller about an Australian heroin addict who escapes a high-security prison in Melbourne in the 1980s, flees to Bombay (now Mumbai), where he lives in the slums, joins the mafia, goes to prison again, makes Bollywood movies, and fights the Soviet Union in Afghanistan. For years it was essential reading for backpackers in India and is widely considered to be the definitive book on Mumbai – except by anyone who is actually from there.

The book is, depending on personal opinion, a rollicking adventure story about one complicated man’s spiritual quest, or an onanistic indulgence in white-saviour fantasy. The self-aggrandising main character is not unbelievable – the heavily touristed parts of India are full of many expats who have made such a mess of their lives that they attempt to reinvent themselves in another place, where the ‘exotic’ country functions as backdrop to their search for personal betterment. The world is full of books about them, as was the residence library. I churned through them, and something common to all began to bug me and gave me something to kvetch about in the evening with the other writers.

The problem with these kinds of stories is that they rarely engage with the people who are born there, who live there, whose options in life might be narrow. The locals are often stereotyped or rote or, at best, a humble, resource-poor but spiritually rich figure who enters the story purely to solve some existential dilemma of the protagonist and then disappears. What happens to them after the story ends?

In so many stories, both protagonist and author miss the point: the complex, pluralistic nation of a billion people doesn’t exist purely for the self-actualisation of wealthy westerners. Where was the book about that? So, I started writing Sweetness and Light.

A caveat: I love travel, I love stories about travel. There’s a reason so many books are set in India: the vastness, the rivers and deserts, the seething socio-political tectonics of the cities. On any given day in Mumbai you’re likely to see something that will completely re-wire your worldview. I am a white man who was brave enough to look at the vast canon of outsider-authored literature about India and say, ‘One more won’t hurt’.

Two real-life misadventures on either side of the country inspired the story. In Goa, a run-in with a con artist that escalated into a very dramatic pyscho-sexual mêlée à trois. And, across the country a decade later, I spent some time in a ’60s-style utopian community, which, like all utopias of the ’60s, ended in tragic-comedic and very dicey territory.

I wanted to pay homage to that tradition of wide-eyed picaresque in a dazzling new place. But I wanted to write about the inherent problem in the idea that you can make yourself a better person by going on holiday. Taking off across the world to start a new life dedicated to say, yoga, is very brave personally, but is in service of a kind of self-actualisation reliant on a web of privilege and status we’re so often blind to.

I found this disparity in all kinds of expat haunts: in hostels, yoga schools and utopian ashrams. You get used to stratification and servants more quickly than you’d think. From embracing a new country in order live more simply and cheaply, to getting used to having servants, to getting used to exploiting vulnerable people is only a few short steps.

'An idea that would have once taken centuries to cross a continent can now be summed up in a Facebook meme.'

If you stop to think about what’s going on in terms of power dynamics and the long, slow wake of post-colonial societies, things get complicated. Turn the intersectional lens a fraction away from the empowerment narrative, and Eat, Pray Love becomes a horror story. Which is what I tried to do in Sweetness and Light. Many of the book’s characters are inspired by real-world charismatic figures – Bikram Choudhury, Anne Hamilton-Byrne, John of God, among many – who appropriate religious and spiritual traditions to justify all kinds of misdeeds.

But perhaps the real bad guy in Sweetness and Light is philosophy – half-baked, half-understood. People have always used religion and spiritual beliefs to justify all kinds of atrocities; it’s nothing new, and it’s nothing major religions don’t do today. But modern rapid advancements in mobility and communication mean that people suffering an existential void can cherry-pick their ideas from hundreds of different schools of thought. An idea that would have once taken centuries to cross a continent can now be summed up in a Facebook meme.

It’s never been easier to embrace new philosophers and inspirations, and never been easier to be suckered. Sweetness and Light is about human need for connection – a novel about the limits of empathy. But it’s also about epiphany: the possibility of trying to reshape yourself in a new place, with a new person. Hope, happiness, being too horny for your own good – some things are universal across all cultures.