- Published: 30 July 2024

- ISBN: 9781761345005

- Imprint: Penguin

- Format: Trade Paperback

- Pages: 320

- RRP: $36.99

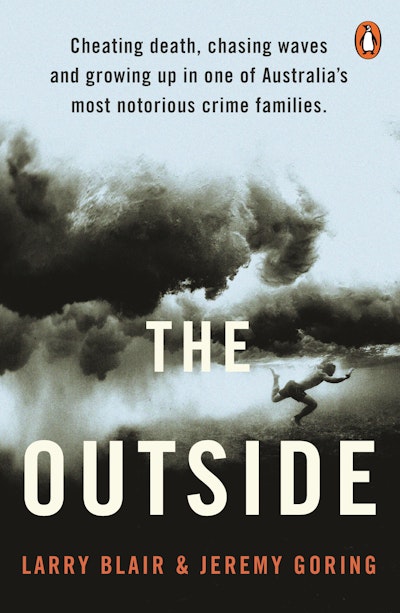

The Outside

Cheating death, chasing waves and growing up in one of Australia’s most notorious crime families

Extract

I’m studying the stuff closely while shuffling my feet about in it. The large particles feel good between the toes: not too fine and sticky, not too coarse. My stomach is a knotted mess, as if I’m waiting in that dark-wood-panelled school corridor. I’m thinking of Mum, who does miracles. Mum can make anything disappear – this is her job. She did it with my baby sister Kellie and me when Dad’s friends were hunting us.

But she isn’t here. And she can’t help.

So God bless you, Mum, wherever you are on this earth.

And Dad, buried under Sydney Airport.

And me, here on the North Shore.

Ψ

This breezy, blue-green and gold heaven has been my second home since 1973 when I was fifteen and needed to leave Australia in a hurry. A very long surf trip to the most remote islands on earth offered me the best way to do it. I got a decent start, making some friends and even earning a little cautious respect from the big guys out in the sea. The ocean had terrified me at first but after a while I became almost at ease among the marching mountains of water – almost. I even started to believe I’d found a niche for myself. But standing here now in front of the simmering mob, I am about to be announced as the winner of the 1979 Banzai Pipeline Masters, and things are going to get very awkward.

People like me aren’t popular in these parts, mostly because of the shit that comes out of our mouths. We’ve also had the brass to enter – and sometimes win – the surfing contests that Hawaiians have always dominated. This has been an insult. The riding of waves was invented here and Hawaii is the spiritual home of world surfing. These are warm-hearted people with a long and fiercely proud history deeply entwined with the ocean. That ocean, and those who live on it, demand respect.

Hawaiians had the sport to themselves for centuries, even after a British sea captain arrived in 1778 and documented locals paddling about on timber planks. Despite a crew member aboard HMS Resolution sketching this other-worldly ‘dance’, no haole (Hawaiian slang that more or less means ‘gringo’) actually got on a board and rode it standing up until pretty recently. I’ve often wondered why it took us so long.

Once foreigners discovered surfing, however, they made up for lost time and the sport grew fast, with the side effect being a foreign invasion here on the island of Oahu over the last few years. It has led to a steadily thickening, toxic undercurrent, concentrated on the North Shore. Things started getting menacing a few years ago, when hot shots like Rabbit, Shaun and Mark arrived. This trio, along with a few others, rewrote the book on what was possible in our sport. They caught the eye of everybody on their way to six world surfing titles between them, and their ever-increasing media profiles wound up tensions even further. Finally, a few faux pas in the press proved to be the last straw and a local posse felt they had to step in – physically.

I tried, I really tried to lie low these last few northern winters. But they got me in the end. I’m a runner-away, but sometimes there isn’t anywhere to run. A lieutenant gave me a violent warning almost as soon as I got back to the island. My attacker was not a big man – shorter than me and of slight build – but he was made of steel wire. In my mind he’s an abused bull terrier fresh from the pound – I’ve always been terrified of him. His physique and angry eyes remind me of my father’s best pal Fletcher, and Fletcher has done some terrible things to people. On the day the man caught up with me, there were too many people watching for me to run, so I just let the blood dribble down my face and kept my fists to myself.

Now, everywhere I go feels tense, inflammable, on edge. Especially out in the water, especially here at Pipeline.

The Banzai Pipeline is the jewel in the crown of North Shore surfing and is still to this day the most famous wave in the world. ‘Pipe’, as it’s colloquially known, has taken more lives than all of the world’s waves combined. It’s one of the most dangerous, snarling, tubular masses of water on the planet, and for many years it was considered unrideable; a perfectly shaped, beautiful blue suicide mission that surfers gawped at and then just walked right past. For this reason, it attracts a curious selection of mongrels, many with a point to prove.

It is a sacred site with its own set of modern-day gods. Gerry ‘Mr Pipe’ Lopez, Rory Russell and up and comer Dane Kealoha are the most revered. All of these great men are proud that Hawaiians have always ‘owned’ the Pipeline Masters, which was, and still is, the most sought-after trophy on the professional world tour. Two of these surfing deities are standing next to me right now doing the same sandy shuffle while we await the judges’ verdict. I already know that I’ve knocked them both out of the competition.

My fellow interlopers, Shaun and Mark, are also in this little group of six expectant finalists, as if it needs to get any more tense.

Dane is fidgeting and hopping about like a boxer limbering up for a fight. If we ever came close to friendship, it ended this morning out there beyond the breaking waves. First when we came to blows during the warm-up period and Dane ripped my lucky Buddha off my neck, and then during the grand final itself just now. I don’t know if relations, or my silver chain, can ever be repaired.

It’s an awkward fact that I pipped him and a few other demigods to the title here last year. It sent shockwaves through the islands. The nasty little haole criminal breezing in and upsetting the natural order . . . and only nineteen etc. etc. My mouth, which I don’t always keep under control, made things even worse. Giddy with victory, I imagined a certain picture as the words came tumbling out during the post-contest press interview, but when those same words floated up off the page a few months later and struck the eyes of my Hawaiian hosts, that picture seemed very different. I sounded like a massive arsehole.

For all these reasons, a second victory is not going to be palatable. Hawaiians do not like second comings of any kind, whether by gods or mortals, as Captain Cook himself discovered on his fateful final voyage, which ended so abruptly right across the straits from here 200 years ago, almost to the day.

Dane Kealoha is far and away the locals’ pick; he is truly of here, like a deep-rooted trunk of dense hard koa, the majestic native hardwood that was once used to make surfboards ridden by the Hawaiian kings. As for me, I’m just some Aussie tumbleweed who blew into town to get away from the New South Wales police.

I am also the uneducated, handsome, blond and very lippy son of two of Australia’s most notorious criminals.

Ψ

Here on the beach surrounded by the lowing crowd and the crush of cameras, Dane is avoiding my gaze. He’s still fidgeting and hopping, looking everywhere but at me. Thank Neptune for that. He’s not going to like what’s about to be announced. Neither are the men in the black shorts.

A low hum from the mob tells me the judges are ready. I pray that if I win and the inevitable fallout ensues, Lucky Buddha can still keep watch over me from the bottom of Pipeline reef.

The Outside Larry Blair, Jeremy Goring

‘Mum once admitted that the only time she thought I was truly safe was when I was out in the water, beyond the breaking waves, in the tranquillity of “The Outside” . . .’

Buy now