- Published: 19 November 2019

- ISBN: 9780241985489

- Imprint: Penguin General UK

- Format: Paperback

- Pages: 256

- RRP: $29.99

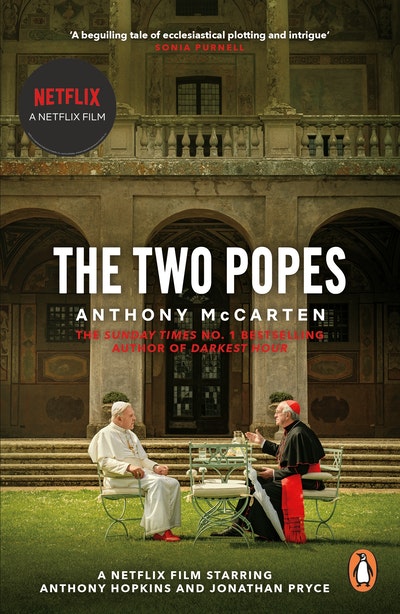

The Two Popes

Official Tie-in to Major New Film Starring Sir Anthony Hopkins

Extract

1

CONCLAVE

“Let me go to the house of the Father.”

These words were whispered in Polish at 3:30 p.m. on April 2, 2005. A little over six hours later, the Catholic Church was set on an unprecedented new course.

Pope John Paul II was dead. Since 1991, the Vatican had kept his illness secret, admitting only in a 2003 statement on the eve of his eighty-third birthday what had already become clear to the world’s then 1.1 billion Catholics. The pontiff’s slow and painful deterioration from Parkinson’s disease had long been agonizing to watch.

Rome had been ablaze with speculation and rumor since February 1, when the pope was rushed to his private wing in Gemelli University Hospital for the treatment of symptoms of “acute inflammation of the larynx and laryngo-spasm,” caused by a recent bout of flu. The press duly assembled for the deathwatch.

Over the following two months, however, John Paul II had displayed more of the same resilience that had characterized his many years of illness. This was, after all, a pope who during his twenty-six-year reign had survived not one but two assassination attempts; he had recovered from four gunshot wounds in 1981 and a bayonet attack a year later. Now, despite multiple readmissions to the hospital and a tracheotomy, he continued to appear at various Vatican windows and balconies to bless the crowds in St. Peter’s Square. His voice was barely audible. He missed the Palm Sunday Mass for the first time during his tenure as pope, but, dedicated to the last, he was presented in a wheelchair on Easter Sunday, March 27, and attempted to make his traditional address. He was described as “[looking] to be in immense distress, opening and shutting his mouth, grimacing with frustration or pain, and several times raising one or both hands to his head.” It was all too much for the estimated eighty thousand devoted Catholics watching below, and tears flowed freely. The pope managed a brief sign of the cross before being wheeled behind the curtains of his apartment.

Over the following six days the Vatican frequently updated the world on his worsening condition, and those who had been hopeful that he might make a full recovery began to accept that his death was only a matter of time. On the morning of April 1 a public statement advised, “The Holy Father’s health condition is very grave.” At 7:17 the previous evening, he had “received the Last Rites.” John Paul’s most trusted friend and personal secretary, Archbishop Stanislaw Dziwisz, administered the sacraments to John Paul II to prepare him for his final journey, by giving him absolution from his sins and anointing him with the holy oils on his forehead and on the backs of his hands, as is done only with priests. (Those not ordained are anointed on the palms of their hands.) Vatican expert and biographer of Pope Benedict XVI, John L. Allen Jr. witnessed this press briefing and described how “the most telling indication of the true gravity of the situation came at the end of the brie ng, when [Vatican spokesman Joaquín Navarro- Valls] choked back tears as he walked away from the platform where he spoke to reporters.”

Surrounded by those who had loved and cherished him for so many years, John Paul II regained consciousness several times during his final twenty-four hours, and was described by his personal physician, Dr. Renato Buzzonetti, as looking “serene and lucid.” In accordance with Polish tradition, “a small, lit candle illuminated the gloom of the room where the pope was expiring.” When he became aware of the crowds calling his name from the vigil below, he uttered words that Vatican officials deciphered as “I have looked for you. Now you have come to me and I thank you.”

Dr. Buzzonetti ran an electrocardiogram for twenty minutes to verify Pope John Paul’s death. Once this was done, the centuries-old Vatican rituals began, elements of which date back to as early as 1059, when Pope Nicholas II radically reformed the process of papal elections, in an effort to prevent further installation of puppet popes under the control of opposing imperial and noble powers, through a decree stating that cardinals alone were responsible for choosing successors to the Chair of St. Peter. Cardinal Eduardo Martínez Somalo had been appointed camerlengo by the late pope to administer the church during the period known as the interregnum (“between the reigns,” which lasts from the moment of death until a new pope is found), and he now stepped forward to call John Paul three times by his Polish baptismal name, Karol. When no answer was received, he struck a small silver hammer on John Paul’s forehead as a sure indication of his death. He was then required to destroy with a hammer the Ring of the Fisherman, or Annelo Pescatorio (the papal ring cast for each pope since the thirteenth century) to symbolize the end of his reign.

And so the death of John Paul was announced to the world. The public outpouring of grief was breathtaking, with many soon referring to him by the prestigious (albeit unofficial) appendage of “the Great,” previously afforded only to pope-saints Leo I (ruled a.d. 440–461), Gregory I (590–604), and Nicholas I (858–867). His body was dressed in bloodred vestments and taken to the Apostolic Palace, where members of the papal administrative offices and agencies of the Catholic Church, known as the Roman Curia, could pay their respects, before being transferred to St. Peter’s Basilica the following day for the beginning of the nine official days of mourning known as the novemdiales, a custom dating back to the novemdiale sacrum, an ancient Roman rite of purification held on the ninth and final day of a period of festivity. An estimated four million pilgrims and three million residents of Rome filed past to give thanks and pray for this most beloved of men, astonishing figures when compared with the previous record of 750,000 people who visited the body of Pope Paul VI in August 1978. John Paul had left instructions that, should he not be alive to read it himself, his final address be read out by the substitute of the Secretariat of State, Archbishop Leonardo Sandri. During mass at the Feast of Divine Mercy held at St. Peter’s Square on Sunday, April 3, Sandri read John Paul’s final message of peace, forgiveness, and love, which told the people, “As a gift to humanity, which sometimes seems bewildered and overwhelmed by the power of evil, selfishness, and fear, the Risen Lord offers his love that pardons, reconciles, and reopens hearts to love. It is a love that converts hearts and gives peace.”

Tough act to follow.

And there was no time to waste. Interregnum tradition demanded that the funeral take place between the fourth and sixth day following a pope’s death. Therefore, it was scheduled for Friday, April 8. Likewise, the conclave to elect his successor must occur no earlier than fifteen or later than twenty days after his death, so was announced to begin on April 18.

The Vatican began planning the funeral with military precision. The responsibility of presiding over events fell to Joseph Ratzinger, as dean of the College of Cardinals—who, despite having no authority over his brother cardinals, “is considered as first among equals” and who, incidentally, had also been John Paul’s right-hand man for twenty-four years. Nicknamed the Pilgrim Pope on account of his globetrotting travels to 129 countries, John Paul II had traveled more miles than all the previous popes in the church’s two-thousand-year history combined, ensuring that heads of state, royalty, and dignitaries from across the globe would be in attendance alongside the crowds of Catholic faithful. A more diverse group of people had gathered at few other moments throughout history, and many opposing nations were united through their mutual respect for the late pontiff. Prince Charles postponed his wedding to Camilla Parker-Bowles to be able to attend alongside the British prime minister, Tony Blair, and the archbishop of Canterbury, Rowan Williams. U.S. president George W. Bush was seen leaning over to shake the hand of staunch Iraq War critic President Jacques Chirac of France, as United Nations secretary-general Kofi Anan watched on alongside former presidents Bill Clinton and George H. W. Bush. The Israeli president, Moshe Katsav, chatted and shook hands with Syrian leader Bashar al-Assad and the president of Iran, Mohammed Khatami, although Khatami later strenuously denied the exchange. It would be the largest funeral of a pope in the history of the Catholic Church, and an estimated two billion people worldwide tuned in to watch the live broadcast on television, with one million of those watching on large outdoor screens specially erected around the city of Rome.

The ceremony began with a private requiem mass inside St. Peter’s Basilica attended by members of the College of Cardinals and the nine Patriarchs of Oriental Catholic Churches, which, though celebrating different liturgies and having their own structures of government, are in full communion with the pope. His body was laid inside a coffin made from cypress wood, a centuries-old tradition that symbolizes his humanity among men, and would later be further enclosed in two caskets of lead and elm, signifying his death and dignity respectively. Inside the coffin a sealed document officially concluding his entire life’s work as pope was placed alongside “three bags, each containing one gold, silver, or copper coin for each year in Pope John Paul II’s reign,” before a white silk veil was placed over his face and hands. That ceremony concluded, the now-closed coffin was carried by twelve papal gentlemen—formerly known as secret chamberlains, these are laymen of noble Roman families who have served the popes for centuries as attendants of the papal household—and accompanied by the slow procession chanting hymns, who made their way into St. Peter’s Square to begin the public funeral.

Many would come to believe that Cardinal Ratzinger’s conduct during this three-hour-long spectacle secured him the papacy. In his homily, amid continual interjections of applause from the crowds, he spoke at length in “human, not metaphysical, terms” of John Paul’s life from his childhood in Poland through to the end of his days in Rome. In his recollection of one of the pope’s last public appearances, the usually unemotional and ultraformal German’s voice cracked as he choked back tears. It was a magnificent and surprising performance to all who witnessed it.

As the funeral drew to a close and the motorcades and he li copters of the dignitaries began to depart, the crowds were left chanting, “Santo subito!” (Sainthood now!) When exhaustion finally descended across the city, people too weary to attempt the journey home lay sleeping on the streets. Talk inside the Vatican and among the world’s media turned to who would succeed the pope now buried in the “bare earth” in the crypt below St. Peter’s Basilica, in accordance with his wishes.

ISSUES FACING THE CARDINAL ELECTORS

With just ten days to go before the 115 cardinals who had assembled in Rome for the funeral would be drawn into conclave to choose the next pope, discreet conversations to promote favored candidates—open campaigning is strictly forbidden—could begin in earnest. This was a delicate balancing act, and the process needed to be handled carefully to avoid the dreaded Pignedoli Principle. This respected theory, conceived by George Weigel of the Ethics and Public Policy Center in Washington, D.C., is named after Cardinal Sergio Pignedoli, hotly tipped by the press to win the 1978 conclave that elected Pope John Paul II. The principle states that “a man’s chances of becoming pope decrease in proportion to the number of times he is described as papabile [the unofficial term used to refer to cardinals who are viewed as potential future popes] in the press.” Technically, all cardinals entering the conclave were eligible candidates for consideration; however, this veneer of simplicity shielded myriad theological and political outlooks that mean electing a successor to the Chair of St. Peter would be far from simple, just as it had been throughout the 729 years since the first conclave, in 1276.

Following an impasse that resulted in an interregnum of almost three years, Pope Gregory X was elected in 1271 and set about developing a format to ease the process whereby cardinals were required to remain in conclave until a decision was reached and even have their food rations reduced to just bread, water, and wine after five days or more of deadlock. Unfortunately, despite efforts to implement these changes when Gregory died, on January 10, 1276, political power plays and infighting would see four popes in as many years after his death and three further interregnums lasting more than two years, in 1292–94, 1314–16, and 1415–17. Centuries would go by until conclaves ceased to last longer than a week, with the election of Pope Pius VIII in 1831. All meetings bar one were held in Rome—which perhaps influenced the Italians’ complete dominance in the role from 1523 until the election of Polish John Paul II in 1978—and had a strictly European result before Pope Francis’s succession in 2013.

The warmth and affection for John Paul displayed by the millions of mourners at his funeral could almost mislead one to believe that the Catholic Church was in better shape than it had ever been. The harsh reality was that this was a church increasingly at odds with modern society, one that seemed unable to find a way to keep pace with, let alone guide, the lives of its followers around the globe. John Paul’s tenure had been like no other in touching the faithful, but dwindling numbers of church attendees in country after country proved that this was not enough to sustain the church’s position. Michael J. Lacey, coauthor of Crisis of Authority in Catholic Modernity, described the Catholic Church as suffering from “an under lying crisis of authority . . . the laity seems to be learning to deal with it to their own satisfaction by not expecting too much from Rome or from their local ordinaries. . . .” What was the church to do to combat these problems?

Problems had been further intensfied by the sexual abuse crisis that rocked the church in 2002 and continues to shake it to this day. The Vatican fervently defended John Paul’s record of handling abuse cases reported to the church, claiming, in 2014, that he did not understand the severity of the “cancer” because the “purity” of his mind and thoughts made this whole situation “unbelievable” to him. But the crisis loomed large in the minds of the assembling cardinals, and as respected Catholic author and journalist David Gibson describes, “the anger over the scandal went much deeper than the sexual abuse itself . . . and centered principally on the abuse of authority that had allowed such crimes to go unchecked for years, even decades. In that sense, the sexual abuse scandals were symptomatic of a larger crisis afflicting the Church, one that centered on how authority—and the power that authority conferred—was wielded in the Church of John Paul II.”

Alongside these key issues, cardinals brought their own regional troubles to the table, among them “secularism in Western Europe, the rise of global Islam, the growing gap between rich and poor in the north and the south, and the proper balance in church government between the center and the periphery.”

Thanks to the positive media attention that had surrounded the funeral, one could easily assume that the swell of public feeling presented the ideal opportunity for the church to shake things up and tackle its institutional failings. Internally, however, opinions were quite the opposite. It was felt that the problems facing the church in the future were so great that radical changes at this juncture could not resolve the dividing issues faced by cardinals from Western and developing nations, while at the same time continuing John Paul’s legacy as an inspirational and engaging man of the people. It was too tall an order, and the majority of cardinals decided they needed a safe pair of hands and a smooth transition to deal with issues that could crush the church irreparably. The only remaining question was, Whose hands?

The Two Popes Anthony McCarten

The remarkable true story of the odd couple in the Vatican - the two living Popes

Buy now