- Published: 16 March 2022

- ISBN: 9781761045523

- Imprint: William Heinemann Australia

- Format: Trade Paperback

- Pages: 384

- RRP: $34.99

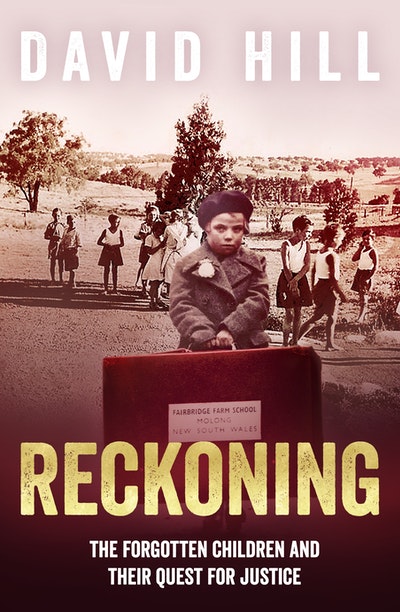

Reckoning

The forgotten children and their quest for justice

Extract

Our first port of call was Port Said in Egypt. We were not allowed ashore to wander around the city because it was, after all, only three years since the Suez Crisis and the British were not popular in Egypt. Wendy Harris wrote about our approach to Port Said in her diary:

Today I feel very excited. The sea is very calm and very blue ... this afternoon I played and watched the shore of Egypt. After tea I watched us draw up at the dock. There were lots of palm trees. Hundreds of little boats have been selling clothes and lots of other things. They throw ropes up to us and someone has to catch it and the passenger asks for something.

We were allowed on shore in both Aden and Colombo, which were great outposts of Empire. We were treated well by the resident senior P&O managers, who appeared to attract almost vice-regal status and were living in huge houses with scores of local servants. It was the first time any of us had ever eaten tropical fruit and most of us were sick eating too much coconut. Nine-year-old John Harris remembers stopping at Colombo several years before on his way to Fairbridge:

Then we got off in Sri Lanka, or Ceylon in those days, and they took us out in to the country and we all had elephant rides and we went through tea paddies and the rice paddies and watched the elephants move logs. It was fantastic.

When everyone was getting a little bored – as you do at the end of the long summer school holidays – finally we reached the Western Australian coast. The weather had cooled by the time we landed at Fremantle on a wet, wintry morning at the end of May. We knew it rained in Australia but this was not what we were expecting. In all the photos we had seen, the place was bathed in sunshine. We were taken on a tour of Perth and for a picnic in Kings Park. This also happened when we reached Adelaide and Melbourne, where local charities put on picnics for the kids destined for the ‘orphanage’. Meanwhile at each port, Perth, Adelaide and Melbourne, a steady stream of adult migrants left the ship to start their new lives in Australia and we continued to the last port of call: Sydney.

We came through Sydney Heads in the early dawn on 4 June. Full of excitement, we rushed to the front of the top deck as we sailed under the Harbour Bridge – looking up we were convinced the funnel would not fit under it. We docked at Pyrmont’s Pier Thirteen, where so many migrants and Fairbridge children had landed before us.

Waiting for us was a huge man we would soon learn to fear and respect. Mr Frederick Kynnersley Smithers Woods – ‘the Boss’ –was the principal of Fairbridge. As soon as he introduced himself, his lack of humour and his no-nonsense manner were evident.

We spent the morning being ordered through a variety of medical checks before being taken by ferry across to the northside of Sydney for a walk around Taronga Park Zoo. After a sandwich at the zoo we came back by ferry in the late afternoon to Circular Quay and were marched all the way through the city and up George Street to Central Station for the overnight steam train to Molong. In what could not have been a bigger contrast with dinner on the Strathaird, we had an evening meal of baked beans on toast in the railway Refreshment Rooms, then boarded the second-class passenger compartment of the steam-hauled, unheated Forbes mail train for the 300-kilometre overnight journey across the Blue Mountains to Molong. I remember we were still dressed in the same clothes we’d arrived in and had enough room to stretch out along the bench seating, but it was bitterly cold and we found it difficult to sleep.

The harsh thud of reality hit us after a fitful night’s sleep when we stepped into the cold pre-dawn darkness of a deserted Molong railway station. It was not yet six in the morning as we passed through the little waiting room and past the dying embers of last night’s fire in the fireplace. The memory of the luxury of the Strathaird was quickly beginning to give way to anxiety and fear.

The temperature was close to freezing as we stood huddled together in front of the station at the bottom of the main street of this little country town. We could see across the road the Mason’s Arms pub, which still had hitching rails for horses.

Most Fairbridge children have similar recollections. David Eva vividly remembers the day he arrived five years earlier as a ten-year-old from Cornwall:

We got on the train and it was so bloody cold. I can remember Woods giving us a blanket. There were kids sleeping in the luggage racks and on the floor and across the seats ... we got to Molong and it was freezing ... I just wondered what the hell I’d let myself in for. I recall Woods being angry that there was no one at the station to pick us up and take us out to the farm and I overheard Dudley and Paddy O’Brien whispering together about how, already, we might plan our escape. Eventually Woods’ wife, Ruth, arrived driving a canvas-covered truck and I was surprised at how rude Woods was to her about her late arrival.

After being ordered into the back of the truck to sit on wooden benches down each side, with our suitcases piled down the middle, we drove six kilometres with a cold wind blowing and the canvas flapping. The twelve of us said very little, just exchanging anxious glances. The levity was completely gone.

It was still dark when we arrived at Fairbridge Farm School. We got out of the truck and were ushered into the big kitchen at the back of the principal’s house, where we were all given a welcome mug of hot cocoa served by three girls who we later learned were ‘trainees’ working as domestic servants for Woods and his family. Nobody spoke as we stood around in a circle wondering what was to happen next.

The first bell of the day had been rung and, unknown to us, out there in the darkness the village was beginning to stir as everyone started their assigned work. Then, one after another, a boy or a girl appeared at the back kitchen door to take one of our party to the cottage we had each been assigned.

The sight of these scruffy Fairbridge kids appearing on the back porch of the house was frightening. Despite it being cold, they were mostly barefoot, wore rough, old clothing, and had unkempt hair – awful haircuts that, we found out later, had been done by other Fairbridge children.

Reckoning David Hill

The story of how David Hill and the other Forgotten Children took on the institutions that tried to break them - and won.

Buy now