- Published: 13 November 2017

- ISBN: 9781864711455

- Imprint: William Heinemann Australia

- Format: Trade Paperback

- Pages: 608

- RRP: $34.99

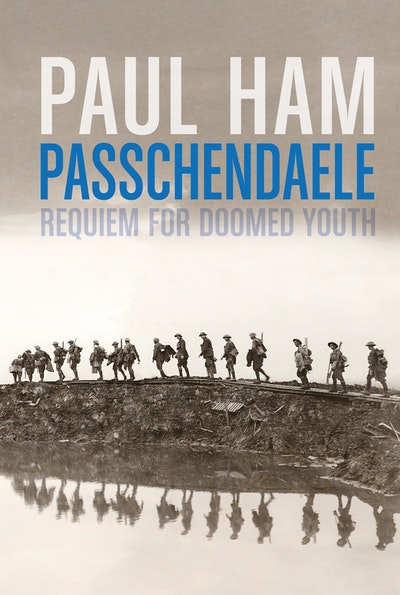

Passchendaele

Requiem for Doomed Youth

Extract

A visitor to Passchendaele today would struggle to imagine this small Flemish town as the object of a field marshal’s obsession and the pivot of the great Flanders Offensive of 1917. In the centre, a few clothes shops and a couple of cafes give onto a desolate square. By the kerb, curiously isolated, stands a bronze relief of the stages of the battle, sculpted by Dr Ross Bastiaan. Opposite stands the church, rebuilt since the war in red, yellow and white stones. British and German artillery destroyed the previous one, along with its cemetery, churning up the remains of the pre-war dead with the casualties of battle. The elaborate graves crowding the grounds post-date the armistice, on 11 November 1918, when the local people returned to reclaim the scab of bones and rubble that had been their home.

A closer look helps us to understand the town’s military relevance: Passchendaele sits on the highest (only about 200 feet above sea level) of a series of concentric ridges, arcs of slightly elevated ground that radiate east of Ypres like the terraces of an enormous, shallow stadium. The Passchendaele-Staden section of the ridge offered a good view and ‘jumping off’ point into German-held territory to the north-east: i.e. the village of Roulers (Roeselare), which served as a vital German supply base, and the plains of Flanders peeling away to the Belgian coast.

Passchendaele village had no strategic importance in its own right; the ridge was merely the first stage of a vast offensive that aimed to liberate Belgium, realising Britain’s original case for entering the war. The Flanders Offensive would be a distinctly Commonwealth campaign. In 1917, the exhausted and mutinous French Army were reduced to playing a defensive role on the Western Front; the Russians were in the throes of revolution; and the Americans had not yet arrived. So the British Army and their Australian, Canadian and New Zealand allies (with small French, South African and Belgian units in support) would confront the most powerful concentration of German troops on the Western Front, who were then being reinforced with fresh troops from the east. On British orders, they were to capture Passchendaele Ridge within weeks (see Map 1), seize Roulers and swing north to the Belgian coast, to fulfil one of the chief aims of the offensive: to destroy the German submarine bases at the ports of Ostend, Zeebrugge and others, whose U-boats were waging unlimited war on Allied shipping.

This would be the prelude to the total rout of the German forces in Belgium, a war-winning scenario dependent on a run of incredible victories, daunting in their ambition even with the help of brilliant command, fine weather and a lot of luck (none of which was forthcoming or guaranteed). The great French marshal Ferdinand Foch was not the only commander who had little faith in what he called a ‘duck’s march’ through the Flanders mud. As we shall see, there were other reasons why, between August and November 1917, the British and Dominion commanders drove their men beyond the edge of the humanly possible to capture the village of Passchendaele, and why the Germans were similarly driven to defend it.

The lessons of the immediate past might have counselled against the offensive. This would be Third Ypres. The First was a defensive battle fought in October and November 1914, in which the Franco- British forces just held the city, though at a huge cost in blood. The Second, from 22 April to 25 May 1915, ended in a stalemate, with Allied casualties of 87,000 against German casualties of 35,000. By the war’s end, there would be five battles of Ypres. With the exception of a single day in 1914, the British and their allies would never yield the once-beautiful mediaeval town of Ypres itself to the Germans. And not until October 1918, at the Fifth Battle of Ypres, would they remove the German forces from the edges of the city’s eastern hinterland, the ‘immortal salient’ – a blister of Allied-controlled territory that swelled up and subsided, but never burst, during four years of war. Hundreds of thousands would be killed or wounded defending or attacking the Ypres Salient; many more would live to remember marching past Ypres’ shell-cratered streets, past the ruins of the thirteenth-century Cloth Hall and cathedral, to the front. In time, defending ‘Wipers’, as the Tommies rejoiced in mispronouncing it, became a rite of passage more terrible than the Somme. The Germans, too, would remember this place with special loathing.

Passchendaele Paul Ham

Passchendaele epitomises everything that was most terrible about the Western Front. The photographs never sleep of this four-month battle, fought from July to November 1917, the worst year of the war: blackened tree stumps rising out of a field of mud, corpses of men and horses drowned in shell holes, terrified soldiers huddled in trenches awaiting the whistle.

Buy now