- Published: 20 August 2018

- ISBN: 9780143789925

- Imprint: Viking

- Format: Trade Paperback

- Pages: 384

- RRP: $34.99

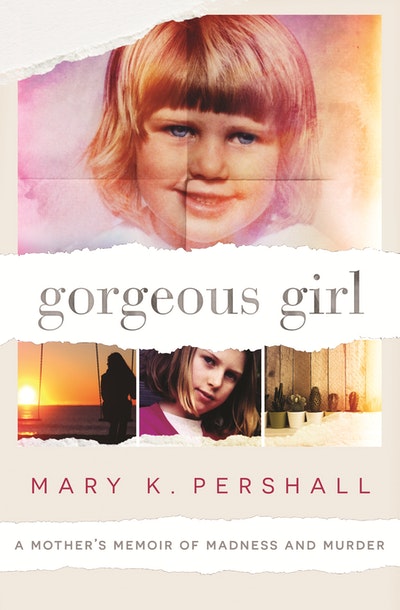

Gorgeous Girl

Extract

Chapter One

The Call came on a sunny afternoon in spring. Every parent dreads The Call, a sombre voice informing you that something unspeakable has happened to the precious being you’ve used your every trick to protect since they were just a clump of multiplying cells. But when your child has told you countless times that she wants to die, and on several occasions has very nearly made that happen, I think you dread it more.

I was already on my mobile, chatting to a friend, out in our unruly backyard. Thirty years before, when John and I jauntily referred to ourselves as ‘young homebuyers on the march’, we were thrilled to find this big block with its many trees and a house full of light, in a little suburb called Oak Park in the northern suburbs of Melbourne.

The friend I was listening to was deeply upset about a row she’d had with another friend of ours, and she needed to vent. So I stood out there beside my veggie garden, occasionally voicing a courtesy ‘hmmm’, while gazing with frustration at the yellowing snow pea vine and the gangly tomato plants. Despite having grown up on an Iowa farm, I hadn’t inherited the knack of coaxing salad from the soil. Herbs were a more satisfying story. The chocolate mint was shining with health, sending out exuberant tendrils from its corner of the bed.

That’s when the two little beeps came, plonked in the middle of one of my friend’s sentences. I reminded myself not to panic. Over the last few months I’d been practising the discipline of not reacting instantly to Anna’s dramas. I told myself the beeps might have nothing to do with her. I mean, I did have other friends who called me. It could well be the one on the other end of the row I was hearing about.

So I waited till the conversation came to a natural end, then I checked my missed calls. Voicemail. I pressed the green light, the one in the shape of an old-fashioned telephone receiver. Easy. No warning that a tiny light would slice my life in two, dividing it neatly between Before and After. It was a man’s deep voice, a police officer. This was about Anna. The officer stated his name; I don’t recall what it was, even though I’m usually good with details like that. I’ve kept a diary since I was fourteen, so I have a pretty comprehensive record of my post-childhood life. There is no entry for that day. On the night of the 22nd of November 2015, I couldn’t bear to write what I’d learned had happened. Across the space allocated for those twenty-four hours, two words are scrawled: Black Sunday.

I think the police officer said in his message that he was calling from a station in the CBD. Again, I can’t be sure. I pressed in the number he gave me and a receptionist answered. I do recall what went through my head when I was waiting to be transferred. Surely she hasn’t killed herself, I thought. Lately she had exhibited an uncharacteristic liking for life. She was eighteen weeks pregnant, so proud of offering her father and me our first grandchild. ‘Wouldn’t Dad love a grandson?’ she had asked. Her dad had a trio of older sisters and a duet of daughters. Of course he would love a grandson.

And then there were the kittens. Even as a toddler barely able to talk, Anna had adored kittens. A few months before Black Sunday, when Anna was having her latest go at a detox program, she needed a place to live. She met a guy at the program who told her about an older man called Johnnie who lived in a big house in the northern suburbs. Johnnie slept in the lounge room and rented out his bedrooms, no deposit or references required. Anna moved in, amid the clutter and the collection of men who, like her, needed shelter. Anna was delighted to discover several cats in residence. She adopted the tamest one, a sweet tortoiseshell she called Chi Chi. I was grateful to Chi Chi for producing five babies, five furrily enchanting reasons for my daughter to keep living a little longer.

‘Miss Pershall?’ The police officer who’d left the voice message had come on the line. ‘We have your daughter in custody.’

‘What? Why?’

The previous summer, her brain marinated in ice, Anna’s behaviour had escalated to the point where her long-suffering dad put his foot down and said that she could no longer live at home. And I had been vastly relieved. When she was growing up, if someone had told me I’d be relieved to have our daughter barred from our home, I wouldn’t have believed them. But then, how could I have imagined the exhaustion, heartbreak and fear that would drive us to that decision?

Anna had calmed down a lot since we made that difficult choice. She swore she wasn’t doing ice. She so wanted to have a healthy baby that she was hardly even drinking, only smoking a little weed to help with her persistent morning sickness.

‘What’s she done?’ I asked the police officer. I couldn’t imagine her even shoplifting, as she spent most of her time these days pinned to the bed with nausea, her kittens in her arms.

‘Umm,’ the officer hesitated. ‘Are you close with your daughter?’

‘Yes.’ I’d seen her two days before, when I had driven to Johnnie’s house at 8.30 a.m. to take her to her antenatal appointment at the Northern Hospital. She’d looked terrible and had been throwing up so much she couldn’t even keep down water. I’d insisted that the hospital admit her for a few hours and put her on a drip.

‘You realise she was living with some older men?’ the officer inquired.

‘Yes . . .’

‘You know the elderly gentleman there?’

Well, come to think of it, you would call Johnnie a gentleman. He was a big Macedonian who spoke broken English at top volume, and he always made me feel more than welcome in his home. ‘Anna mama!’ he would boom when I arrived. ‘You good mama. You the best mama!’

He wasn’t actually ancient; I thought he might be in his late sixties – making him only a few years older than me. But he was so crippled by arthritis that he couldn’t really walk. He could only shuffle a few steps with the aid of two sticks and plenty of painkillers. He spent his days on a chair in his kitchen, and he was always surrounded by friends. Some of them lived in the house, while others were regular visitors. They interrupted each other with gusto in a variety of languages as they drank glass after glass of white wine from a cask perched on the edge of the kitchen table.

If I stepped into the kitchen, Johnnie would order one of the younger men to vacate their chair. ‘Anna mama . . . you sit! You want drink? Have drink!’ He would tell me what a fine job I had done raising Anna. At least a hundred times he had said to me, ‘She good girl. She like my daughter. I call her Daughtie!’

‘Unfortunately,’ the police officer informed me, ‘there’s been an assault involving your daughter. The elderly man has passed away.’

I’d heard of people feeling like they were outside themselves, watching a terrible event unfold as if to another person, and now I know that phenomenon is real. I could hear someone screaming, moaning ‘Noooooo!’ over and over again. I’d wandered from the garden into the house by then, and I was sitting on the edge of our bed. John appeared at the door. My husband, with whom I had made a perfect, blue-eyed baby twenty-seven years before.

‘What’s wrong?’ There must have been alarm in his eyes, but that’s not what I remember. What I remember is what I sobbed to him. ‘She’s killed Johnnie!’

When I stopped screaming, I still had the phone clamped to my ear. The police officer was there and sounded surprised at the level of my distress. ‘Did you know the gentleman well?’

‘Yes! Of course I knew him!’ Perhaps my tone overstated my relationship with Johnnie. But I certainly knew he did not want to die. He had dreams and plans. He often told me, with hope in his eyes, that he had a booking at the Northern Hospital to get both his knees reconstructed. And the guys in his house teased him about a Russian girlfriend, telling me he was trying to get her to Australia.

Two days earlier, while Anna was lying in the hospital having fluids dripped into her veins, I had taken Johnnie to the post office. It was quite a business, helping him from his front door to my car, then lowering his bulk into the passenger seat of my little Honda Jazz. It was even harder getting him into the post office, but I parked illegally right out the front, and we managed. After I’d parked the car in a proper spot and then gone into the post office to help him, I found him leaning heavily against one of the waist-high desks provided for customers, signing and parcelling up documents. Being an inveterate stickybeak, I certainly would have read any bits of the documents that I could. But they were printed in a script indecipherable to me.

‘Would you like to speak to your daughter?’ the police officer asked.

My daughter. My squishy, giggly baby who I breastfed for fifteen months. My little toddling angel with the white-blonde hair.

‘No!’ So many times I had called her number and longed for her to pick up because I desperately needed to hear her voice. ‘I don’t want to speak to her! I can’t speak to her!’

‘All right.’ His voice was kind. ‘Ring me back on this number when you’re ready.’

What happened then? Did John and I hold each other? Probably. The day exists in snatches in my head. Later, I was out in the garden again, and saw John through our big kitchen window. He didn’t know I was looking. He was standing by the sink, with his head in his hands. The classic gesture of despair and horror. His hair was silver but he was still the lean, tall, strong guy who took me in his arms for a waltz at a colonial dancing class thirty-five years before and never let me go.

I called my older daughter, Katie, desperately hoping she would pick up. I remember having a deep, primal need for her to be with me. Thank goodness she answered her phone. She and her partner, Tom, were living on a property that his mother owned, on a billabong near Wangaratta. She said she would come down on the next train. Just as she has done since before she could talk, she would do what she could to help me whenever I needed it.

If only I could have willed the train to arrive immediately! I so wanted Katie by my side. But I had to wait four hours. Somehow the minutes passed, and as they did my shock began to morph into my default feeling towards Anna: concern. She would not have meant for Johnnie to die. She must have been so sorry. Just like she had been a few weeks ago when she rang me, sounding devastated. I was standing in Coles, in the aisle they keep at Arctic temperature, between the milk and the frozen fish.

‘I hit Johnnie!’ I could hear the shock in her voice.

‘What?’

‘I hit him with his walking stick, twice.’

‘Why?’

‘Because he wouldn’t stop yelling!’

‘Is he hurt?’

‘No, he’s okay . . . But Mummy, I hit him!’

I gave her a piece of advice then. Just one. This was our arrangement, honed over the months since she had moved out. I wouldn’t nag, wouldn’t tell her to be positive, because she hated me doing that. But I couldn’t just watch and say nothing. So I was allowed one piece of advice per phone call or visit.

‘Just walk out when you get that angry,’ I said. ‘Get out of there. Walk to the library or shops until you feel like you can control yourself.’

‘Okay,’ she whispered. But in my heart I knew she wouldn’t walk to the library. It had been over a year since she’d had the courage to go anywhere on her own, unless she was fuelled by ice, and she didn’t want to do that now.

This conversation beside the frozen fish had replayed itself over and over in my head, and each time I was shocked again. But it had never occurred to me that Anna would actually hurt Johnnie. He called her Daughtie and she called him Daddy. I had watched her lean over his chair and plant a kiss on his balding head. On Black Sunday, my mind was hurled into a dark mishmash of images where time was meaningless, so I don’t know how long it took for me to prepare myself to hear Anna’s voice. Maybe half an hour after I first talked to him, I rang the police officer back. He told me that Anna was not available. She was being questioned. The officer would arrange for her to ring me when she could. Now I was waiting for both my daughters.

My phone rang. A private number. It wasn’t Anna. It was another young woman, with a voice full of light and energy. ‘Hello, I’m Gina. I’m looking after Anna this afternoon.’ She sounded like a waitress at a trendy restaurant. But she was a lawyer, putting in a few hours of pro bono work.

‘Is Anna okay?’ I asked.

‘Well, she’s emotional, but she’s coping.’

‘Is someone watching her, so she can’t hurt herself?’

‘Oh, yes. We’ll be keeping an eye on her,’ Gina assured me brightly. ‘She’s still being questioned right now. I’ll stay in touch with you through the afternoon.’

‘Did she hit Johnnie with his stick?’

‘Sorry?’

This is how I imagined it. She got mad at him, like before, she lost control and this time she hit him more than twice. ‘He must have died of a heart attack,’ I suggested.

‘No.’ With that monosyllable, Gina’s chirpy voice had changed dramatically. Suddenly it was full of sorrow. ‘No, Mary, that’s not how it happened.’

She didn’t say any more, just that she’d talk to me later.

Finally, I went online to see what the papers had to say. The Age had an item about the incident. There were no names yet, just that on the previous night, the 21st of November, a 27-year-old woman had assaulted a 67-year-old man, and he had died of upper-body injuries.

Upper-body injuries . . . I knew what that was shorthand for. She had stabbed him.

Gorgeous Girl Mary K Pershall

Award-winning writer Mary K. Pershall details her heart-rending personal experience of raising a beloved child who couldn't cope with reality, and ends up in a maximum-security prison convicted of murder.

Buy now