- Published: 13 June 2023

- ISBN: 9781761046988

- Imprint: Vintage Australia

- Format: Trade Paperback

- Pages: 384

- RRP: $32.99

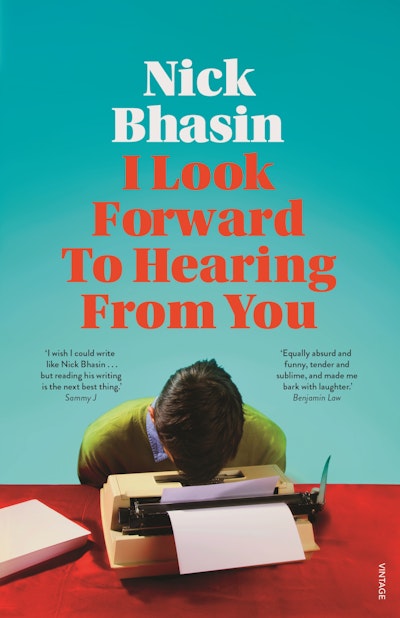

I Look Forward to Hearing from You

Extract

Relatives were lowering my mother into the ground when my father implored the crowd to sing ‘Amazing Grace’ for the third time.

It was a fairly typical move for him. An over-the-top request that couldn’t be turned down in the most uncomfortable of moments. The priest, who had already told everyone to go and serve the Lord, was caught off guard. He froze and put his hands up like he was being held at gunpoint. And so the people sang.

Before they could start the second verse, my father interrupted and told them to sing the song again. My father was not only getting people to sing ‘Amazing Grace’ over and over again – he was only singing the one verse he knew. The first one with the ‘how sweet the sound’ bit. He didn’t know the six other verses. I wasn’t sure he knew the song even had other verses. But other people did. And when they tried to continue singing the song properly, he had them start over so they could sing the part he liked.

Some mourners paused. A few of them looked at each other to make sure they would not be singing alone. The others, especially those in my mother’s more cynical family, did not appreciate being made to sing. They wanted all of this to be over and my father was prolonging the pain.

Also, it was cold for May. And I was in shock.

A few days ago, it was Thursday and I was at the Coffee Bean in Los Feliz when I spoke to my mother for the last time. She was annoyed that my sister Valentina hadn’t called her in a week. She wasn’t going to call her, though.

‘I don’t care how far away you are or what you’re doing,’ she insisted. ‘You always need to call your mama.’

She reminded me that I was twenty-seven and there was still time to go to graduate school. I reminded her that I was on the verge of unleashing a televisual masterpiece so consequential the world would never be the same.

Friday afternoon, I was spending too much of my quickly dwindling savings on a TV/VCR/DVD combo when my father called to tell me she was in the hospital. I caught the red-eye from LAX and by the time I landed in Newark on Saturday my mother was gone. My last words to her were an unduly harsh critique of a movie neither one of us had seen. Now it was Monday.

‘Everyone, please,’ my father said, leaving his place next to us by the dark hole in New Jersey. ‘One more time. Please.’

Valentina leaned over to me.

‘Are you going to do something about this?’ she asked.

Since he quit his corporate lawyer job to pursue, as he put it, ‘communal brotherhood with his fellow man’, my father had developed an affinity for church music. Raised with both Hinduism and Sikhism in Bombay, he’d been in the country since the ’60s and had a lot of attachments to American culture – Gene Autry movies, the songs of Jackie Wilson, any sitcom set in New York, which reminded him of treasured days living in the city with his friends. These things seemed to be revered on the same level as classic Bollywood films and music.

‘Jackie Wilson is the bloody greatest,’ he’d say, ‘So is Robin Williams.’

I’d remind him that Robin Williams was sued for stealing the idea for his most popular movie – Immigrant Barber – which also happened to be my father’s favourite American film.

‘Americans will sue over anything,’ he’d say. ‘In India, if someone steals your intellectual property, you – tck . . .’ and he would make a stabbing motion, pantomiming a prison shiv attack. Most people were nervously amused by my father’s tall tales of extreme Indian justice. But of course, there was nothing amusing about what was happening here.

Fewer people were singing. Most were hanging their heads, exhausted. Titi Diana, my mother’s sister, looked at her watch and around the cemetery, expecting that there would be a long line of people waiting to bury their own dead behind us. I saw her mouth the words ‘Come on’. Even Abuelita, who stopped speaking English the minute she left Brooklyn and moved back to Puerto Rico, could tell something was not right.

‘We can’t just let him humiliate himself out there,’ Valentina said.

‘This is what a broken man looks like. Let the people see it. Remember it. Write poems about it.’

Valentina looked at me like she wanted me to tell me to lighten up, but she couldn’t. Not today, when we knew there would never be light again.

‘Once more. Please . . .’

I Look Forward to Hearing from You Nick Bhasin

'I wish I could write like Nick Bhasin … but reading his writing is the next best thing.'SAMMY J'Bhasin hits that sweet spot of emotional depth while also being absurdly funny.'MARK HUMPHRIES

Buy now