- Published: 19 February 2019

- ISBN: 9780241982105

- Imprint: Penguin General UK

- Format: Paperback

- Pages: 384

- RRP: $26.99

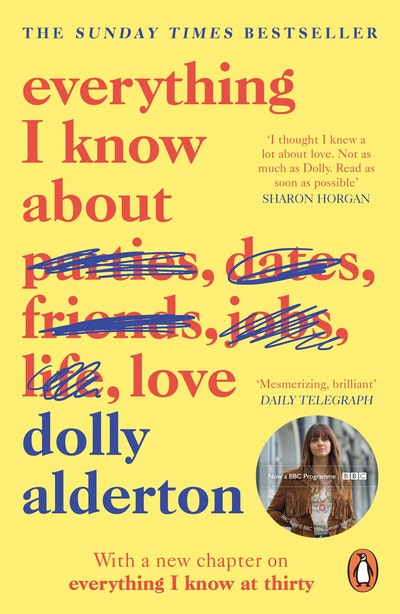

Everything I Know About Love

Extract

I can still remember it now, note for note. The tinny initial phone beeps, the reedy, half-finished squiggles of sound that signalled a half-connection, the high one note that told you some progress was being made, followed by two abrasive low thumps, some white fuzz. And then the silence indicated that you had broken through the worst of it. ‘Welcome to AOL,’ said a soothing voice, the upward inflection on ‘O’. Followed by, ‘You have email.’ I would dance around the room to the sound of the AOL dial-up, to help the agonizing time pass quicker. I choreographed a routine from things I learnt in ballet: a plié on the beeps; a pas de chat on the thumps. I did it every night when I came home from school. Because that was the soundtrack of my life. Because I spent my adolescence on the internet.

A little explanation: I grew up in the suburbs. That’s it; that’s the explanation. When I was eight years old, my parents made the cruel decision to move us out of a basement flat in Islington and into a larger house in Stanmore; the last stop on the Jubilee line and on the very furthest fringes of North London. It was the blank margin of the city; an observer of the fun, rather than a reveller at the party.

When you grow up in Stanmore you are neither urban nor rural. I was too far out of London to be one of those cool kids who went to the Ministry of Sound and dropped their ‘g’s and wore cool vintage clothes picked up in surprisingly good Oxfams in Peckham Rye. But I was too far away from the Chilterns to be one of those ruddy- cheeked, feral, country teenagers who wore old fisherman’s jumpers and learnt how to drive their dad’s Citroën when they were thirteen and went on walks and took acid in a forest with their cousins. The North London suburbs were a vacuum for identity. It was as beige as the plush carpets that adorned its every home. There was no art, no culture, no old buildings, no parks, no independent shops or restaurants. There were golf clubs and branches of Prezzo and private schools and driveways and roundabouts and retail parks and glass-roofed shopping centres. The women looked the same, the houses were built the same, the cars were all the same. The only form of expression was through the spending of money on homogenized assets – conservatories, kitchen extensions, cars with in- built satnav, all- inclusive holidays to Majorca. Unless you played golf, wanted your hair highlighted or to browse a Volkswagen showroom, there was absolutely nothing to do.

This was particularly true if you were a teenager at the mercy of your mother’s availability to cart you around in her aforementioned Volkswagen Golf GTI. Luckily, I had my best friend, Farly, who was a three-and-a-half-mile bike ride away from my cul-de-sac.

Farly was, and still is, different to any other person in my life. We met at school when we were eleven years old. She was, and remains, the total opposite to me. She is dark; I am fair. She is a little too short; I am a little too tall. She plans and schedules everything; I leave everything to the last minute. She loves order; I’m inclined towards mess. She loves rules; I hate rules. She is without ego; I think my piece of morning toast is important enough to warrant broadcast on social media (three channels). She is very present and focused on tasks at hand; I am always half in life, half in a fantastical version of it in my head. But, somehow, we work. Nothing luckier has ever happened in my life than the day Farly sat next to me in a maths lesson in 1999.

The order of the day with Farly was always exactly the same: we’d sit in front of the television eating mountains of bagels and crisps (though only when our parents were out – another trait of the suburban middle classes is that they are particularly precious about sofas and always have a ‘strictly no eating’ living room) and watching American teen sitcoms on Nickelodeon. When we’d run out of episodes of Sister, Sister and Two of a Kind and Sabrina the Teenage Witch, we’d move on to the music channels, staring slack-jawed at the TV screen while flicking between MTV, MTV Base and VH every ten seconds, looking for a particular Usher video. When we were bored of that, we’d go back on to Nickelodeon +1 and watch all the episodes of the American teen sitcoms we had watched an hour earlier, on repeat.

Morrissey once described his teenage life as ‘waiting for a bus that never came’; a feeling that’s only exacerbated when you come of age in a place that feels like an all-beige waiting room. I was bored and sad and lonely, restlessly wishing the hours of my childhood away. And then, like a gallant knight in shining armour, came AOL dial-up internet on my family’s large desktop computer. And then came MSN Instant Messenger.

When I downloaded MSN Messenger and started adding email address contacts – friends from school, friends of friends, friends in nearby schools who I’d never met – it was like knocking on the wall of a prison cell and hearing someone tap back. It was like finding blades of grass on Mars. It was like turning the knob of the radio on and finally hearing the crackle smooth into a human voice. It was an escape out of my suburban doldrums and into an abundance of human life.

MSN was more than a way I kept in touch with my friends as a teenager; it was a place. That’s how I remember it, as a room I physically sat in for hours and hours every evening and weekend until my eyes turned bloodshot from staring at the screen. Even when we’d leave the suburbs and my parents would generously take my brother and me for holidays in France, it was still the room I occupied every day. The first thing I would do when we arrived at a new B&B was find out if they had a computer with internet – usually an ancient desktop in a dark basement – and I would log on to MSN Messenger and unashamedly sit chatting on it for hours while a moody French teenager sat behind me in an armchair waiting for his go. The Provençal sunshine beat down outside, where the rest of my family lay by the pool and read, but my parents knew there was no arguing with me when it came to MSN Messenger. It was the hub of all my friendships. It was my own private space. It was the only thing I could call my own. As I say, it was a place.

My first email address was munchkin_1_4@hotmail.com which I set up aged twelve in my school IT room. I chose the number 14 as I assumed I would only be emailing for two years before it became babyish; I gave myself room to enjoy this new fad and its various eccentricities until the address would expire in relevance on my fourteenth birthday. I didn’t start using MSN Messenger until I was fourteen and in this space of time would also try out willyoungisyum@hotmail.com to express my new passion for the 2002 winner of Pop Idol. I also tried thespian_me@hotmail.com on for size, after giving a barnstorming performance as Mister Snow in the school’s production of Carousel.

I reprised munchkin_1_4 when I downloaded MSN Instant Messenger and enjoyed the overflowing MSN Messenger contacts book of school friends I had accumulated since the address’s conception. But, crucially, there was also the introduction of boys. Now, I didn’t know any boys at this point. Other than my brother, little cousin, dad and one or two of my dad’s cricketing friends, truly, I hadn’t spent any time with a boy in my entire life. But MSN brought the email addresses and avatars of these new floating Phantom Boys; they were charitably donated by various girls at my school – the ones who would hang out with boys at the weekend and then magnanimously pass their email addresses around the student body. These boys did the MSN circuit; every girl from my school would add them as a contact and we’d all have our fifteen minutes of fame talking to them.

Where the boys were sourced from broadly fell into three categories. The first: a girl’s mother’s godson or some sort of family friend on the outskirts of her life who she had grown up with. He was normally a year or two older than us, very tall and lanky with a deep voice. Also lumped into this category was someone’s schoolboy neighbour. The next classification were the cousins or second cousins of someone. Finally, and most exotically, a boy who someone had met when they were on a family holiday. This was the Holy Grail, really, as he could be from absolutely anywhere, as far-flung as Bromley or Maidenhead, and yet there you’d be, talking to him on MSN Messenger as if he were in the same room. What madness; what adventure.

I quickly collated a Rolodex of these waifs and strays, giving them their own separate label in my contacts list, marked ‘BOYS’. Weeks would pass talking to them – about GCSE choices, about our favourite bands, about how much we smoked and drank and ‘how far’ we’d ‘been’ with the opposite sex (always a momentously laboured work of fiction). Of course, we all had little to no idea of what anyone looked like; this was before we had camera phones or social media profiles, so the only thing you’d have to go on was their tiny MSN profile photo and their description of themselves. Sometimes I’d go to the trouble of using my mum’s scanner to upload a photograph of me looking nice at a family meal or on holiday, then I’d carefully cut out my aunt or my grandpa using the crop function on Paint, but mostly it was too much of a faff.

The arrival of virtual boys into the world of our school friends came with a whole set of fresh conflicts and drama. There would be an ever- turning rumour mill about who was talking to whom. Girls would pledge their faith to boys they’d never met by inserting the boy’s first name into their username with stars and hearts and underscores either side. Some girls thought they were in an exclusive online dialogue with a boy, but these usernames cropping up would tell a different story. Sometimes, girls from neighbouring schools who you’d never met would add you, to ask straight out if you were talking to the same boy they were talking to. Occasionally – and this would always go down as a cautionary tale in the common room – you would accidentally expose an MSN relationship with a boy by writing a message to him in the wrong window and sending it to a friend instead. Shakespearean levels of tragedy would ensue.

There was a complicated etiquette that came with MSN; if both you and a boy you liked were logged on, but he wasn’t talking to you, a failsafe way of getting his attention would be to log off then log on again, as he would be notified of your re- entry and reminded of your presence, hopefully resulting in a conversation. There was also the trick of hiding your online status if you wanted to avoid talking to anyone other than one particular contact, as you could do so furtively. It was a complex Edwardian dance of courtship and I was a giddy and willing participant.

These long correspondences rarely resulted in a real-life meet-up and when they did, they were nearly always a gut- wrenching disappointment. There was Max with the double- barrelled surname – a notorious MSN Casanova, known for sending girls Baby G watches in the post – who Farly agreed to meet outside a newsagent in Bushey one Saturday afternoon, after months of chatting online. She got there, took one look at him and freaked out, hiding behind a bin for cover. She watched him call her mobile over and over again from a phone box, but she couldn’t face the reality of a meet-up in the flesh and legged it back home. They continued to speak for hours every night on MSN.

I had two. The first was a disastrous blind date in a shopping centre that lasted less than fifteen minutes. The second was a boy from a nearby boarding school who I’d spoken to for nearly a year before we finally had our first date at Pizza Express, Stanmore. For the following year, we had a sort of on-off relationship; mainly off because he was always locked up at school. But I would occasionally go to visit him, wearing lipstick and carrying a handbag full of packets of fags I’d bought for him, like Bob Hope being sent out to entertain the troops in the Second World War. He had no access to the internet in his dormitory, so MSN was out of the question, but we remedied this with weekly letters and long calls that made my father age with despair when greeted with a three-figure monthly landline phone bill.

At fifteen, I began a love affair more all-consuming than anything that had ever happened in the windows of MSN Instant Messenger when I made new friends with a wild-haired girl with freckles and kohl-rimmed hazel eyes called Lauren. We had seen each other around at the odd Hollywood Bowl birthday party since we were kids, but we finally met properly through our mutual friend Jess over dinner in one of Stanmore’s many Italian chain restaurants. The connection was like everything I’d ever seen in any romantic film I’d ever watched on ITV2. We talked until our mouths were dry, we finished each other’s sentences, we made tables turn round as we laughed like drains; Jess went home and we sat on a bench in the freezing cold after we got chucked out of the restaurant just so we could carry on talking.

She was a guitarist looking for a singer to start a band; I’d sung at one sparsely attended open- mic night in Hoxton and I needed a guitarist. We started rehearsing bossa nova covers of Dead Kennedys songs the following day in her mum’s shed with the first draft of our band name being ‘Raging Pankhurst’. We later changed it to, even more inexplicably, ‘Sophie Can’t Fly’. Our first gig was in a Turkish restaurant in Pinner, with just one customer in the heaving restaurant who wasn’t a member of our family or a school friend. We went on to do all the big names: a theatre foyer in Rickmansworth, a pub garden’s derelict outbuilding in Mill Hill, a cricket pavilion just outside of Cheltenham. We busked on any street without a policeman. We sang at the reception of any bar mitzvah that would have us.

We also shared a hobby for the pioneering method of multi-platforming our MSN content. Early on in our friendship, we discovered that since the conception of Instant Messenger, we had both been copying and pasting conversations with boys on to a Microsoft Word document, printing them out and putting the pages in a ring-binder folder to read before bed like an erotic novel. We thought ourselves to be a sort of two-person Bloomsbury Group of early noughties MSN Messenger.

But just as I formed a friendship with Lauren, I left suburbia to live seventy-five miles north of Stanmore at a co-ed boarding school. MSN could no longer serve my curiosity around the opposite sex; I needed to know what they were like in real life. The ever-fading smell of Ralph Lauren Polo Blue on a love letter didn’t satisfy me any more and neither did the pings and drums of new messages on MSN. I went to boarding school to try to acclimatize to boys.

Everything I Know About Love Dolly Alderton

The wildly funny Sunday Times bestseller about growing up and navigating all kinds of love along the way

Buy now