- Published: 20 August 2019

- ISBN: 9781760892852

- Imprint: Penguin

- Format: Paperback

- Pages: 304

- RRP: $26.99

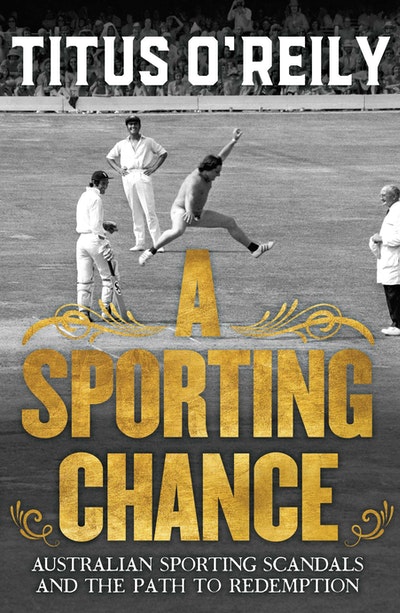

A Sporting Chance

Australian Sporting Scandals and the Path to Redemption

Extract

The Good Bloke has usually won a lot of silverware or has huge potential, and is also friends with lots of other sportsmen and media commentators. They are always forgiven for making fools of themselves, and suffer no consequences for indiscretions that would result in the rest of us being escorted from our workplace by someone with ‘People and Culture’ in their title.

Once upon a time the Good Bloke lived a free and easy life, but times are changing. This once impervious predator is now in danger. New, strange and terrifying threats have risen: smartphones, social media, integrity units, women in positions of power.

These changes raise questions that once seemed unthinkable. Is there no longer a place for the loveable larrikin in Australian sport? Does the rise of the nanny state mean photographing a model in the shower against her will and sending those photos to mates will begin to have serious consequences? Is the path to forgiveness as open as ever, or are our Star Athletes just one ball-tampering incident away from extinction?

Anatomy of the species

In 2010, Rugby League legend Mal Meninga was a happy man. He had just coached Queensland to a 3–0 series whitewash in the State of Origin.

This wasn’t anything new; New South Wales losing the State of Origin was an annual occurrence, like the coming of autumn, or Sam Stosur being bundled out in the first round of the Australian Open. In fact, ancient peoples used NSW losing the State of Origin series as the sign to start preparing the land for planting, and there’s a pillar at Stonehenge that aligns with the sun each year at the exact moment NSW lose.

In 2010, though, Meninga had won all three games in the series, the first time he’d achieved that as coach. As he answered reporters’ questions in the afterglow of a hard fought 23–18 victory, he waxed lyrical about what made his Queensland team so great.

‘Their belief is fantastic and their mateship, which is really important, is second to none as well. They’ll do everything they possibly can for their mate to be successful.’

Unintentionally, Meninga had identified both the building blocks of a great team and the worst excesses of the Star Athlete.

Mateship, or friendship on steroids, is a uniquely Australian obsession. It places equality, loyalty and friendship – usually between men – on a pedestal so high it is technically in low-Earth orbit.

So powerful is our idea of mateship, so bound up with the ANZAC spirit, sport and the adversity of colonial times, that in 1999 John Howard seriously considered including it in the Australian Constitution. Drafted by Les Murray, Howard wanted this preamble added: Australians are free to be proud of their country and heritage, free to realise themselves as individuals, and free to pursue their hopes and ideals. We value excellence as well as fairness, independence as dearly as mateship.

In many ways mateship is an admirable trait, but Howard’s line of thinking polarised people and was ultimately knocked back, showing a remarkable level of common sense compared to, say, the United States, where the right to shoot people is enshrined in the constitution.

Howard’s attempt to raise mateship to a holy tenet even led Les Murray1 to observe that mateship was ‘blokeish’ and ‘not a real word’.

Richard Walsh, in his 1985 essay ‘Australia Observed’, wrote, ‘The ultimate accolade in Australia is to be a “good bloke”, meaning someone who is gregarious, hospitable, generous, warm hearted, and with a good sense of humour. In Australia it availeth a man nothing if he makes himself a fortune and is not a good bloke!’

On the surface this sentiment seems fine, but in the pressure cooker of the sporting world, mateship gets a bit twisted. It can exclude people, mainly women, and lead to an atmosphere so suffocating it’s hard to think outside the group. So powerful is the distortion field created by mateship in a high-pressure environment, it can even make appointing David Warner vice-captain of the Australian cricket team seem like a good idea.

Like many good things, mateship can become toxic in high doses.2 In the framework of a team, where everything is about achieving something together, every part has to be dedicated to the greater whole. This extends beyond the players to coaches and administrators, and even the million-dollar businesspeople who get seduced by the glamour of sport.

Let’s face it, achieving something together is a lot easier if everyone conforms to a shared world view, and that’s certainly the case for teams that pull off great victories.3 It’s even easier if everyone likes each other and believes that they’re among a great group of blokes. (It also means your premiership reunions won’t be as awkward as that time John Howard had a bowl on national television.) The default response to any challenge becomes ‘do everything you can for your mate to be successful’. That’s why Meninga thought mateship was so important.

A problem emerges, however, when a member of a close-knit group of mates does something awful, ridiculous or plain stupid. And in sport, that’s not uncommon. The us-against-them mentality, so useful on the field, is then extended well beyond the boundary line.

Usually the result is a full-throated defence of the player in question. It’s not entirely disingenuous either, as it must be hard to believe that a teammate you achieved so much with on the field, who you’ve seen do great things, who’s had your back, would be seriously lacking in some other area of their character. After all, if your teammate isn’t a good bloke, what does that say about you? Does it mean you’re mates with people who aren’t good blokes? Are you, yourself, not a good bloke? Talk about an existential crisis.4

This is why, on various NRL and AFL panel shows, you’ll often hear a player say something like this about a teammate: ‘Yeah, Davo’s disappointed with himself for fighting those four guys and all the public urination, but he’s a great bloke and he knows he’s messed up. Of course, coming hot on the heels of his sexual assault conviction, it isn’t ideal. This is all so out of character.’

Then, sometime in the following week, the player who has transgressed delivers an apology that isn’t really an apology. And once the dust has settled, a media outlet will probably sign Davo to a lucrative contract to provide special comments for their coverage that are usually anything but special. Give it a few years and everyone will be referring to Davo as ‘a bit of a loveable rogue’ or ‘one of the game’s great characters’.

That’s because the sports media has as many Good Blokes roaming wild as sports teams do. It’s an industry dominated by ex-players and reliant on maintaining good relationships in the sporting world.

So players and the media instinctively team up to offer defences of the Good Blokes in their midst.

The result of this group defence is that the term ‘good bloke’ no longer means what it says. Like ‘fun run’, it often actually means exactly the opposite.

The combination of this group defence and fans’ desire for success means sports stars get away with things that would be unthinkable in any other industry. Try joking with a bunch of blokes at your work about drowning a female peer and see how long you stay employed.

1 Not Mr Football Les Murray, of SBS fame, but poet Les Murray. Sorry for mentioning a poet in a sports book, especially considering such an excessive amount of government funding goes to the arts, starving the sporting community of much-needed cash.

2 Even West Coast Coolers can be toxic in large amounts, something I discovered on Alan Bond’s yacht once, while in the company of the singer Sade. It’s a long story.

3 As a member of a sports team, you can only do superficially non-conforming things, like having a funny haircut. Anything deeper than that threatens this conformity. Tattoos used to be non-conformist but are now so common that not having one is the way to stand out.

4 Apologies for using the word ‘existential’ in a book about sport. And no, I don’t know what it means either.

A Sporting Chance Titus O'Reily

Ridiculous Australian tales of sporting stuff-ups and forgiveness by the bestselling author of A Thoroughly Unhelpful History of Australian Sport.

Buy now