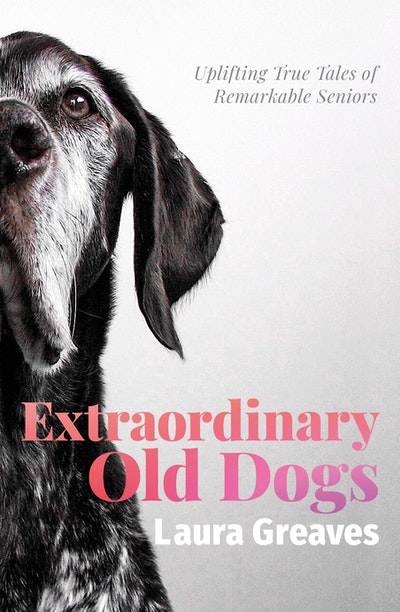

Meet Maggie, unofficially the world’s oldest dog – and officially dairy farmer Brian McLaren’s best mate for nearly thirty years.

Self-confessed ‘crazy dog lady’ Laura Greaves is back with more extraordinary canine tales, this time she’s found uplifting stories of remarkable seniors. ‘Loving an old dog is different, certainly, but it is a unique and beautiful chapter in the story of their life. Never forget what an honour it is to be there to share it,’ writes Greaves in the book’s introduction.

In the passage below we meet a Victorian kelpie who lived to the ripe old age of ‘at least thirty years old’.

If there’s one thing about dogs and ageing that everyone knows, it’s this: one year of a dog’s life is equivalent to seven human years.

We all agree that when Fido blows out the candle on his first birthday cake, he is at the same level of physical maturity as a seven-year-old child. Every subsequent year is worth another seven human trips around the sun, so if he makes it to twelve years old, he’s eighty-four in people terms. Those rare good boys and girls that make it into their teens are pushing 100 human years – a good innings in anybody’s estimation.

We all seem to absorb this tidbit of dog trivia from the ether, and few of us ever question it. But here’s the thing: it’s not true.

It’s hard to pinpoint where the ‘dog years’ myth began; it seems to have been around forever. But for as long as it has existed, veterinarians and other canine experts have been trying to debunk it. The truth is that all dogs age differently, and according to a heap of varying factors, including breed, size and overall health.

In reality, a ten-year-old Chihuahua has aged to about the same extent as a 56-year-old person, while a Bulldog at ten would be around sixty-five in human years. Meanwhile, a Great Dane that has clocked up a decade of good living is roughly equivalent to a 75-year-old biped.

The one-year-equals-seven equation also cannot account for those very special dogs that reach twenty or older. If the myth were correct, it would mean a twenty-year-old pooch’s body had weathered 140 years of wear and tear. While that would be amazing, it’s very unlikely, if not impossible.

Well, impossible except for a Victorian kelpie named Maggie.

Photo credit: Brian McLaren

When Maggie passed away on her owner Brian McLaren’s dairy farm in April 2016, he believes she was at least thirty years old. (We might once have said that was 210 in human years, but now we know better.) He can no longer prove exactly how old she was... but officially speaking or not, her astonishingly lengthy life probably makes Maggie the longest-lived dog in the world.

Brian has been a dairy farmer in Woolsthorpe, in southern Victoria, all his life; the farm has been in his family for four generations. He’s had working dogs all his life, too. They help to move and corral the cattle, and they’re tireless toilers who love every moment of it.

Some of his dogs have had more aptitude for the job than others, though. ‘I’ve always had dogs, some successful and some unsuccessful. A successful dog is one that’s got a really good temperament, is not aggressive, and is easily trained,’ Brian says. ‘If they’re a bit scatterbrained and you can’t control them, they’re not much good for dairy cows.’

In the early nineties, the farm dog was Jack the blackand-tan kelpie, whose enthusiasm for rounding up cattle was unmatched by any of Brian’s previous dogs. As soon as he heard ‘go back’ – his instruction to go and bring the cows from the paddock to the dairy for milking – he’d be off like a shot.

‘Jack would go anywhere for cows, especially in the morning. We’d go out the door at 5 a.m. and he’d be right there. We’d tell him to “go back” and he’d disappear into the darkness, and by the time I got into the dairy, all the cows would be there,’ he says.

Sadly, Jack’s promising career was curtailed by a shocking accident. He was struck by a milk tanker and died when he was only about five years old. The loss was so devastating that Brian vowed never to have another working dog; he would herd the cattle on his motorbike rather than risk such grief again.

But his wife, Sue, had other ideas.

‘I’d decided that was it – no more dogs for me. I was that upset. But Sue convinced me that I should go and see this guy who had dogs advertised that he couldn’t get rid of,’ he says.

In country terms, the seller was a near neighbour – he lived about 20 kilometres west of Brian’s property. Brian decided the purebred kelpies he was advertising were worth a look.

When he met the eight-week-old female puppy, his first impression wasn’t so much positive as staggeringly impressed.

‘This little puppy was out in the paddock chasing cows. She was just a little ball of fluff, but she was wandering around in the paddock,’ says Brian. ‘She couldn’t do much – the cows were up, looking at her – but she wanted to chase. She was out looking to work. That’s what got me over the line with her: she was interested in chasing cows already.’

So it was decided. The McLarens’ farm would have another dog after all. It was a lucky break for the puppy in more ways than one – her breeder told Brian that the rest of the litter was destined for an animal shelter, because he didn’t know what to do with them.

Brian, Sue and their three sons – Joe, Chris and Liam – bundled the puppy into the car and hit the road. On the drive home, they debated possible names for their new ‘employee’. With a minimum of fuss, she was christened Maggie.

One way Brian knows for sure that Maggie lived to be at least thirty is that his youngest son, Liam, wasn’t yet at school when Maggie joined the family, so he can’t have been more than four years old; Brian actually thinks he may have been even younger. When Maggie passed away in 2016, Liam was thirty-four.

Before long Maggie was a McLaren through and through – and as Brian’s first encounter with her had suggested, she was a natural with cows. She was the only working dog he had, because she was the only working dog he needed.

‘Dairy farmers usually only have one working dog at a time. Sheep farmers have multiples because they’ve got to control big mobs of sheep, and it’s all about getting them on the truck,’ he explains. ‘But rounding up cows has got to be gentle, and Maggie was exceptionally gentle. She was one out of the box.’

Laidback and easy to train, Australian kelpies are known for their smarts and indefatigable work ethic. They commonly work with sheep, cattle, goats, pigs and even poultry. Farmers and stockmen say that, when it comes to mustering livestock, one good kelpie can do the work of several hired hands.

Maggie was a shining example of her breed. She had instinct in spades, and being both gentle and highly intelligent she was able to herd cattle with almost no guidance from Brian.

‘She didn’t take a lot of training. When she was young I could just whistle and send her for the cows. I didn’t have to yell and scream at her. She knew what she had to do,’ he says. ‘I might be in the middle of a ten-hectare paddock on the motorbike and she’d be on the other side, walking behind the cows. We’re talking seven hundred cows.’

Maggie quickly developed her own unique way of doing things. While many cattle dogs will bark their charges into formation, she preferred a quieter approach. She liked to make the cows come to her.

‘When she had to shift a cow, she wouldn’t bark. She’d just lie down on her belly and wait for it to walk towards her, and then nip it on the nose,’ says Brian. ‘The cow would turn and walk away and she’d follow it. She wouldn’t bark unless I told her to – she’d wait until I told her to “speak up”.’

Maggie also had a competitive streak. While she did her work on four paws, Brian did his on two wheels, mustering and droving the cows on a motorcycle. The machine instantly became Maggie’s nemesis.

‘Most of our droving is done on a motorbike, and she hated being beaten by the bike. She just hated it.’ Brian laughs. ‘She wouldn’t go on the back of the bike – she wanted to run alongside it and race it. She’d disappear and then turn up behind the cows.’

She was fastidious about her work, too, refusing to knock off for the day until every cow was accounted for. ‘When she was bringing them home for the night, if I left her on her own she could bring them in by herself. If she missed a couple and it was still daylight, I could send her out again and she’d get the ones she missed.’

It wasn’t just cows whose occasional tardiness frustrated Maggie. If her boys – Joe, Chris and Liam – weren’t home from school on time, she would vent her spleen to anyone within earshot.

‘She knew the kids got home off the school bus at ten past four every afternoon. You could set your watch by her: every day at 4.10 p.m. she’d go out the front and wait,’ says Brian. ‘If they weren’t on time, she’d bark until they arrived. She did that until well after the kids had grown up and left school.’

And so it went, year after happy year. The seasons changed and changed again, but Maggie’s dedication to her job never wavered. Every morning and afternoon she would be raring to bring the cows from their paddock to the dairy and every evening she’d guide them home to bed.

Her only flaw – if it can even be called a flaw – was that Maggie was terrified of thunderstorms. On stormy nights, she had to be secured for her own safety. ‘Maggie was never a house dog as such – never inside except during storms. She hated thunder and would run a mile, so she’d get locked up on the back verandah at night.’

Aside from that, the little black-and-tan kelpie was fearless. Nothing fazed her, and she thrived on farm life like she was born for it – which, essentially, she was.

.jpg)