Sixteen-year-old Jarryd Roughead’s initiation to senior football was anything but a lucky break.

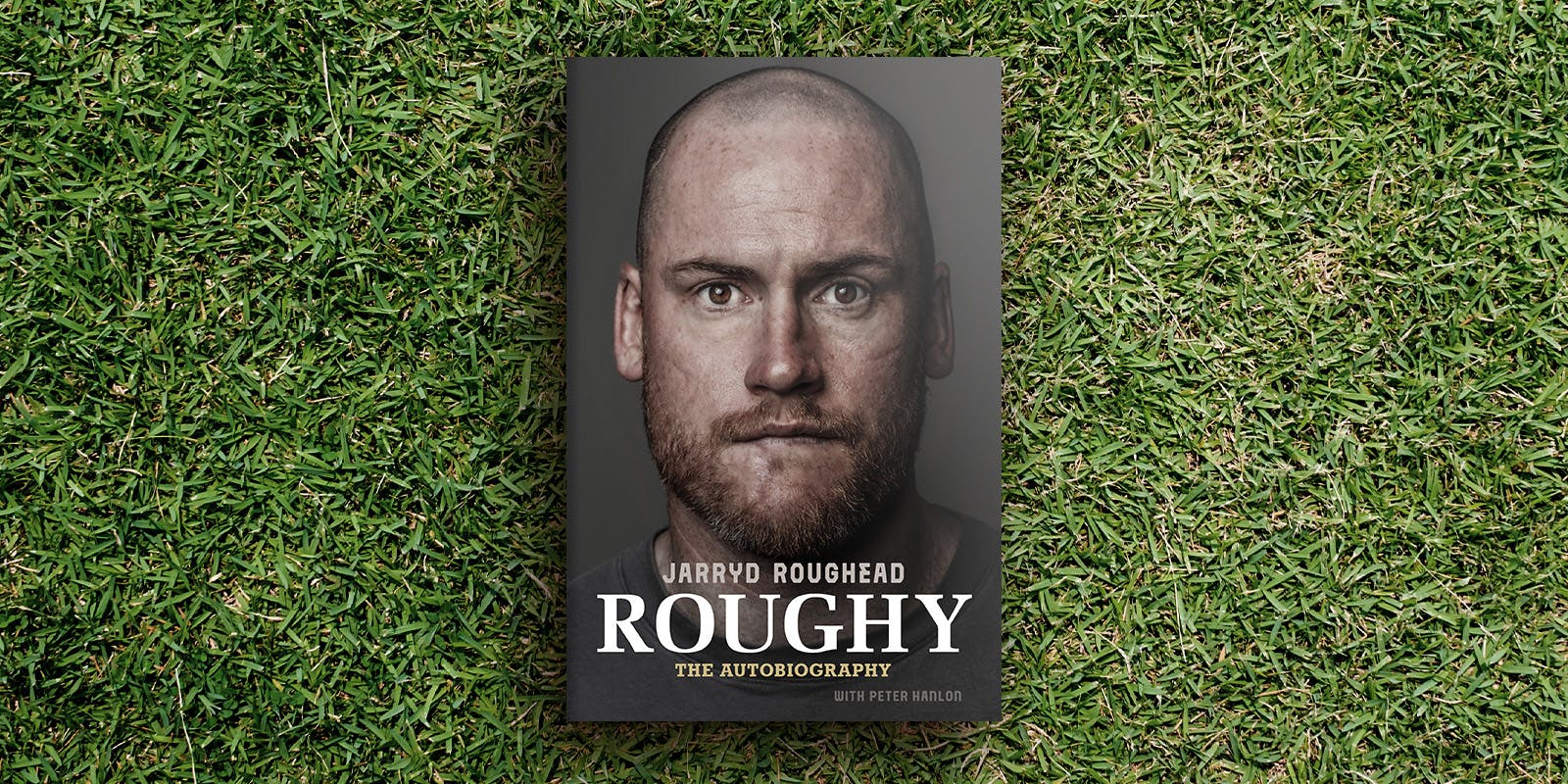

Four AFL premierships, two All-Australian selections and a Coleman Medal – there’s not much in Australian Rules football that Jarryd Roughead hasn’t achieved. When confronted with a cancer diagnosis and the rigors of the subsequent treatment, in his worst moments Roughead would draw on all the grit and determination he'd learned as an elite athlete. And through it all he never stopped believing he would not only survive, but play his beloved game for his beloved club once more.

Roughy is the story of a country boy who not only became an AFL star, but was a key player in a Hawthorn team that will be remembered as one of the greats of any era. Like all the best sporting success stories, you can trace the foundations of greatness back to humble beginnings. In the passage from Roughy below, Roughead recalls a leap of faith and a run of luck at the Leongatha Parrots.

Going into 2003 I started pre-season training with a couple of mates, doing swims and whatnot early in the morning. The idea of training and fitness making you better was sinking in. I’d train with the under-16s then hang around and train with the seniors too. It was Dunks’ first year as player-coach, and after a few weeks he said to Dad, ‘This boy of yours is going to be too good for under-16s, he could play seniors with me.’ Dad’s reply was, ‘He’s 16!’ Which was nothing compared to Mum’s reaction when he got home and told her. But Dad took her to meet Dunks and he told them, ‘Don’t worry, I’ll look after him.’ So that was it, I was in.

My first senior game was against Moe at Moe, and I kicked two goals five. Goalkicking! Yeah, maybe it was an issue my whole career. I could run a bit – I wasn’t heavy then and played anywhere from forward pocket to flank and wing. Dad had worn number 4, which I’d proudly had on my little Parrots jumper as a kid. It was available when I got picked for the seniors and to run out in Dad’s number was a huge thrill.

The next week we played Wonthaggi at home on a Sunday afternoon and it felt like most of Leongatha was there. I played on Dean Rice, who’d had a long career at St Kilda and Carlton before becoming player-coach of Wonthaggi. I kicked the first goal of the game, and another one near the end, and we ended up winning a tight game. Senior footy felt pretty good.

My third game was at Maffra, and we drove up in Dad’s van. We had a few key players out, then Dunks pulled out with a back or hamstring injury. In the last quarter, I saw the ball switch and went to go in that direction. Their centre half-back saw me move, cleaned me up, and broke my collarbone.

Having said he’d look after me, Dunks wasn’t even playing! Mum and Dad weren’t happy at all.

It was a long, quiet trip home. Dad, Mum and I sat up front in the refrigerated HiAce, me with my arm in a sling and in tears because my footy world had just fallen apart. I’d done a few training sessions with Gippsland Power’s TAC Cup team, and the Victorian under-16 championships were two weeks later in Bendigo. Things were just starting to happen and now I had a busted collarbone.

It’s the only broken bone I’ve ever had, but there’s not much you can do with a broken collarbone, just put the arm in a sling and rest. It was my left arm and I write right-handed, so I couldn’t even get out of school. How stiff can you be?

I went up to Bendigo and watched the championships to be around the group, and then I got a letter from Vic Country saying I’d still made the team for the national under-16 championships. I was surprised, but you don’t ask any questions in that situation. After six weeks out and with my shoulder healed I came back and played four games in the Leongatha under-16s, just so I could say Dad had coached me, then played the last two in the seniors and three finals.

We lost to Maffra, beat Sale in the preliminary final, and played Maffra again in the granny. There was a big crowd, utes backed up against the fence with couches on the back and blokes working their way through eskys full of beer, classic country footy stuff. I kicked the first goal of the game – Dunks gave me a handball, I swung onto my left and popped it through. I was feeling pretty good, thinking I was gunna win a senior premiership at 16. I played okay, kicked the last of the game too, but we fell about four goals short.

I didn’t realise it at the time, but that was an initiation to the biggest day in any footballer’s life, learning what goes into winning a flag. We had a good team – Dunks and Huddo, Mick Johnson, the Paveys who were very good – but we were old and sore. Before the game I watched the doctor jab blokes in the rooms just to get them out on the ground.

I had no idea how much more of that I’d see, how many other grand finals days I’d be part of. Playing in a premiership for your home town is the dream, simple as that. If country footy was still a bit rough back then I didn’t notice, and I don’t remember seeing anything that frightened me. I loved footy, everything about it – being around the older players at the club, sitting in the rooms soaking it all up as they told their stories.

There was a tradition when Leongatha won a footy premiership that was passed down from generation to generation and team to team. The train doesn’t run through town anymore, but back in the day someone worked out that you could set off the level crossing at the start of Roughead Street by rubbing the tracks at a certain point with a pole. In the days after grand final wins, celebrating footballers would be walking from the rooms to the pub, or from the pub back to the rooms (you get the picture), and the lights would start flashing and the bells would ring, drivers stopped and wondered why there was a train coming at this time, and then out of the dark came half a dozen nude blokes running along the tracks.

I wanted to be one of those blokes, a Leongatha premiership player. Losing hurt, but at 16 I thought grand finals would happen every year. The AFL was a long way away, but closer than I realised.