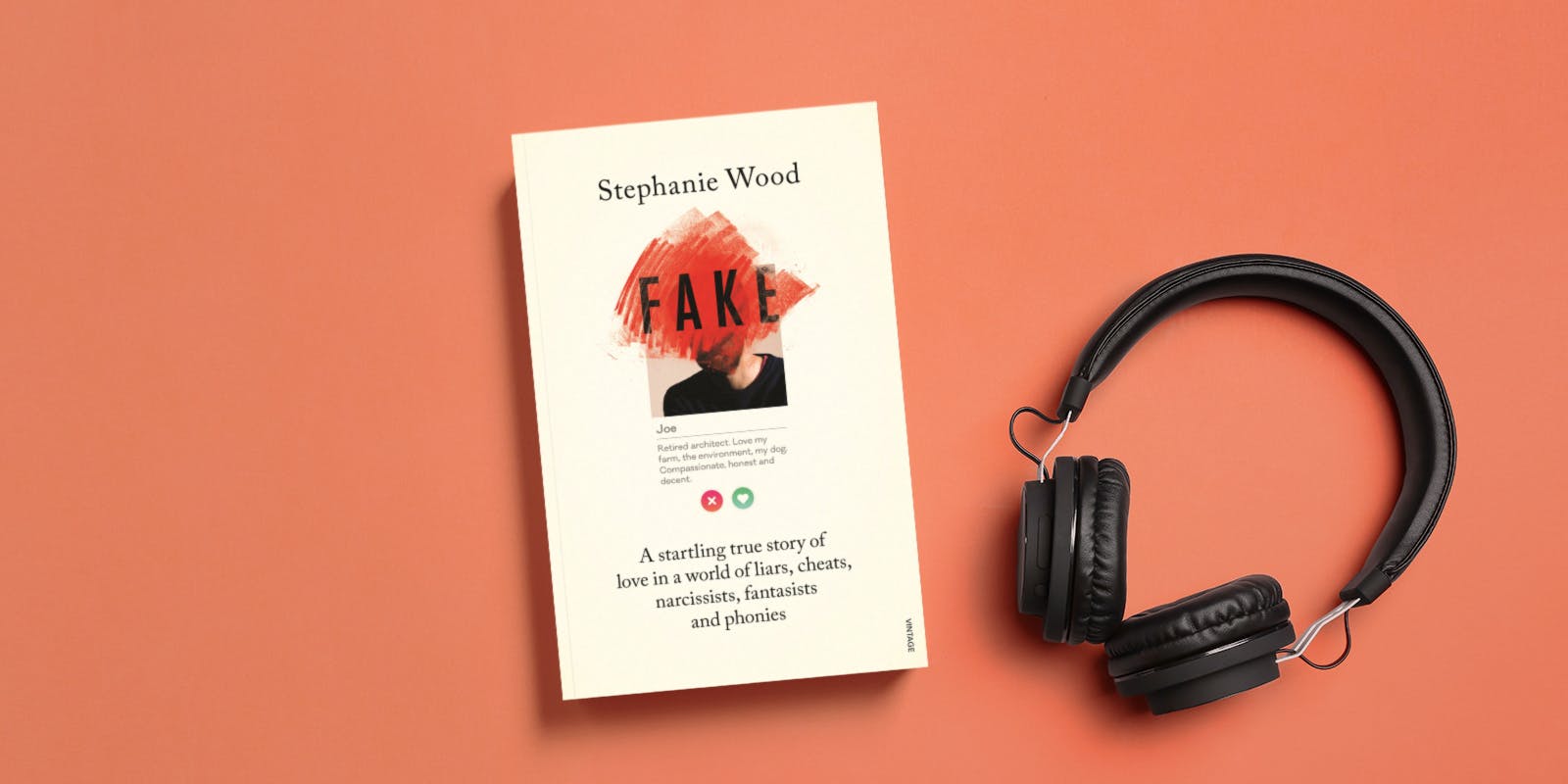

The award-winning long-form features writer reveals the confronting and cathartic aspects of writing Fake.

Why tell this story?

As a long-form features journalist, I adore telling rich, complex stories about people and society, stories that explore who we are and why we behave in the ways we do. But these stories don’t come along every day. And then, into my own life, one such story arrived. It was full of suspense, human mystery, psychological complexity, heartache and darkness, and gave me the opportunity to investigate so many interesting threads. And I was inside it, which gave me a perspective that is almost impossible to get when you are reporting someone else’s story.

Ultimately, I couldn’t not write this story.

That doesn’t mean though that I wasn’t riddled with doubt about the wisdom of writing Fake. I thought long and hard before committing to do it because I could see that it might have any number of long-term, if not life-long implications for me personally.

But Oprah Winfrey encapsulated everything for me, and more succinctly: “Speaking your truth is the most powerful tool we all have.”

In revisiting this chapter in your life, what have you found most confronting?

Writing Fake was a form of self-psychoanalysis. It helped me see with so much more clarity than I ever had before the very distinct patterns of my relationships with men over a lifetime. And that was really difficult. In a nutshell, and I know any number of other women have the same story: throughout my lifetime I have allowed men to treat me poorly because I have not valued myself enough and (cliche alert!) that has a lot to do with my childhood. In Fake, I quote the American philosopher Martha Nussbaum: “We cannot understand [someone’s] love … without knowing a great deal about the history of patterns of attachment that extend back into [their] childhood. (Upheavals of Thought: the Intelligence of Emotions, Cambridge University Press, 2001)

What have you found most cathartic?

In my research for Fake I interviewed a number of experts, including anthropologists, psychologists and cognitive scientists, to help me understand why I was vulnerable to the man I call “Joe” and why he behaved in the way he did. I learned that my vulnerability to his manipulations was not just about patterns of attachment. There are other complex and intersecting physiological and psychological factors that I know about now that played a part, including the fact that, when we’re in love, the cortical circuits in our brains are not sifting information and guiding us towards sound decisions as well as they normally do. In terms of Joe’s behaviour, it was enormously cathartic to discover through my research that his patterns of behaviour are consistent with those of someone who has a personality disorder. Once all this information came together, I started to feel whole again.

To whom have you turned for guidance during this time? And what advice has helped you through the writing process?

I actually turned inward as I wrote and spoke very little about the book or the writing process. My mother heard more about it than anyone else, and certainly on more than one occasion heard tears coming down the end of the phone — mostly because as I know now, writing a book when there is a tight deadline is exhausting, stressful and relentless. It sucked me dry. It’s a common piece of writing advice but by far the wisest as far as I’m concerned: don’t think too far ahead because if you do, you’ll break down and never recover. I spent a long time developing a chapter-by-chapter structure for the book but once that was in place, I had to trust that it would give me direction as I went forward. So I tried then not to think too far ahead so as not to panic; just as far as the end of the section I was immersed in.

What apprehensions do you have releasing this book into the world?

The idea of exposing my private life, my vulnerabilities, my regrets, and my flaws to the world filled me with horror. I knew though, that by exposing myself as I have done, the book would be stronger. And all the feedback I’ve had to it so far has confirmed that. I’ve had hundreds of messages from people thanking me for revealing my vulnerabilities. We all have them. To see that someone else has them is comforting, even life-affirming.

If you could, what would you say to your past self as this relationship began?

Run now! (The journalist/writer in me wishes I’d wired him, or at least tried to record some of our conversations. Damn, why didn’t I think to do that!)

Looking back, what, if anything, would you have to say Joe?

Please, can you donate your brain to science so someone can study what makes it tick.

How has this period of your life impacted your perception of trust?

Sadly, I have a much more jaundiced view of the world. And it’s not just because of my experience with Joe. As a result of writing both the original Good Weekend article that led to the book and now the book itself, I have heard from hundreds of people who have had Joes in their life. I have heard the most devastating stories. Before Joe, I probably believed that most people in the world were fundamentally trustworthy, fundamentally decent. Rightly or wrongly, I take the opposite view now.

What message do you hope readers take away from Fake?

Primarily, we all deserve respect and indeed safety in our relationships. We might not have the power to change how someone chooses to treat us, but we do have the power to walk away from bad treatment. That said, I do not underestimate how much more difficult walking away is for some, especially those who feel under physical threat, or who have children in a difficult relationship, or who are financially dependent.

What do you think society has to learn from this story?

I think we have become too tolerant as a society of deceit. In all forms, political or private, deceit should be called out and condemned.

.jpg?w=690&h=344)