A small mark historian Geoffrey Blainey left on the parlance of our times.

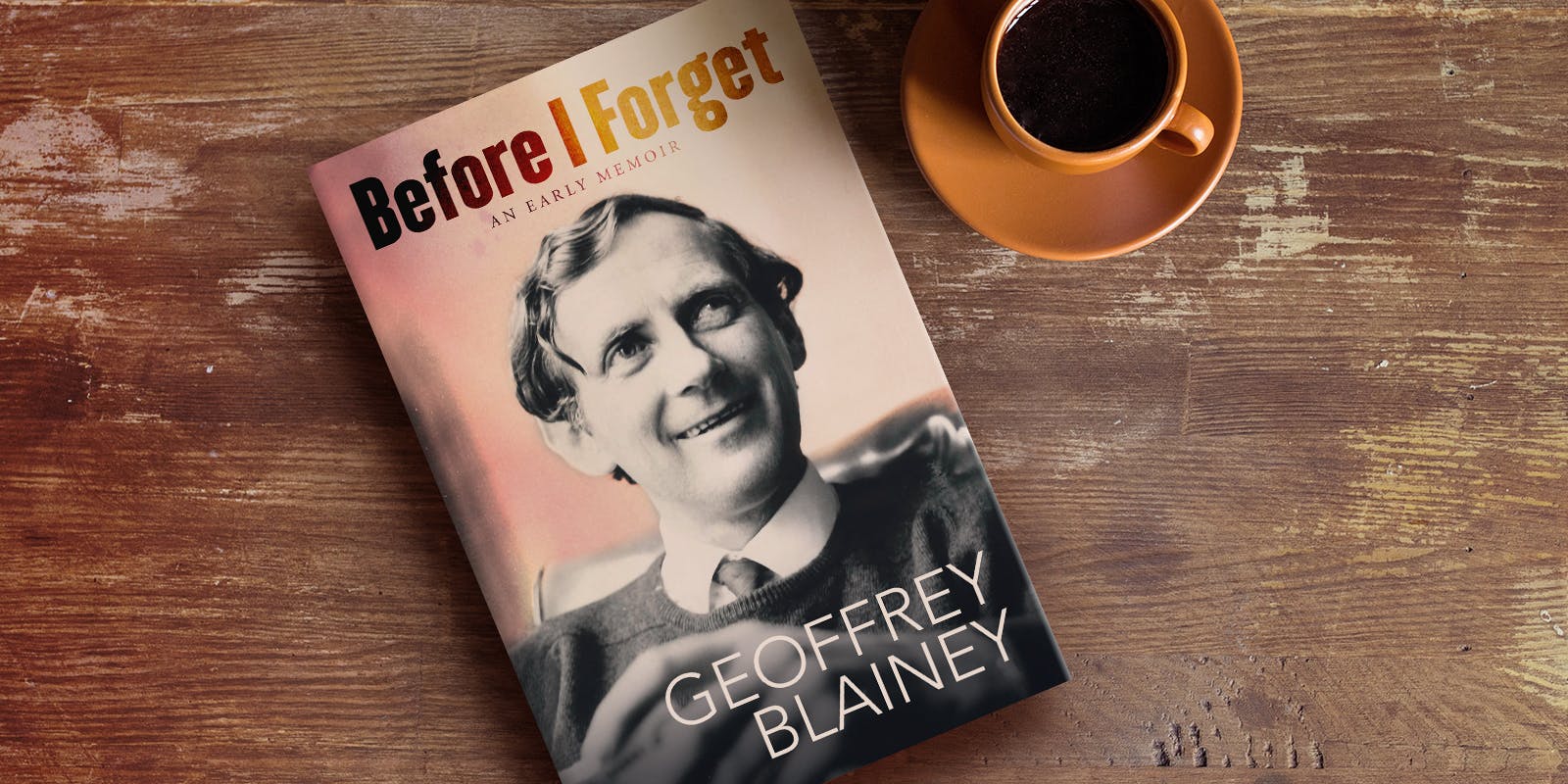

As one of Australia’s best-known historians, via his dozens of books, and a variety of academic and philanthropic positions, Geoffrey Blainey has played a large hand in explaining modern Australia. He has served the federal government in various roles, including as chair of the Australia Council. And in 1988 he was awarded the Britannica Prize for ‘excellence in the dissemination of knowledge for the benefit of mankind’. His memoir, Before I Forget, tracks the first 40 years of his life – exploring the experiences and influences that shaped his curiosities and career. The book is also a fascinating social history in and of itself. And among the chapters of his life story, he reveals the people, places and events that left impressions on his broader worldview. In the passage below, he details an unexpected impact one of his titles made on the Australian vernacular.

I had set out to cross the red world some months before The Tyranny of Distance was ready for publication. Not until we returned to London in December 1966 did I find a waiting parcel containing three copies of the book. With pleasure I saw the dust jacket and then some of the printed pages and illustrations.

The book appeared in what was then a rare sequence, being published first as a cheapish paperback at a price of $1.95, and a couple of years later as a more expensive hardback and finally as a coffee-table book. The paperback editions carried a brilliant dust jacket, designed by Brian Sadgrove. I can say so impartially because I had no part in its creation. The cover showed the bottom half of the globe, in brilliant blue, with a white sailing ship mysteriously travelling upside down.

At first The Tyranny of Distance did not sell in large numbers. Most of the reviews were very favourable but reviews do not necessarily sell a book. Indeed it gained because some of the reaction to it was unfavourable. Several scholars were not convinced by my chapter, which argued that Britain settled Australia primarily for strategic reasons. Their argument did not convince me but like other authors I am not an impartial judge!

News of the book spread by word of mouth. It defied the bookshops’ general rule by selling more in its second year – and also in its third year – than in its first year of publication. It was reprinted again and again. Eventually it appeared as a hardback with Macmillan in Australia, while in England it was offered by the History Book Club to its members. The Japanese translation came much later. Probably it was the first book in Australia to begin as a paperback and to blossom – in the space of half-a-dozen years – into a hardback and then an expensive coffee-table volume.

For a time the phrase tyranny of distance was anchored rather than airborne. There was only an occasional sign that it would acquire a life of its own, independent of the book. In March 1968 it was officially used to describe an event that in a dramatic way was to weaken that tyranny. A satellite, stationed far above the earth, could now transmit television news and programs between the Northern Hemisphere and the Southern. And on the day when the first images were transmitted between Japan and Australia, a speaker proclaimed that this was another blow against ‘what an Australian historian has called the tyranny of distance’ – or words to that effect. I felt secretly pleased.

Another sign that the phrase might soar was a headline in the London Times, written in 1970 when a reigning pope made his first visit to Australia. The paper announced that Pope Paul VI was conquering ‘the tyranny of distance’. The origin of the phrase was not stated nor was there a reason why it should be. Year after year it was employed by more journalists and politicians, mostly in Australia but sometimes in North America and Europe. I could have no objection to the popularising of it. I did not own it; the language belongs to all.

The book aroused controversy among historians. One chapter was the pivot of their argument. Such influential and able historians as A.G.L. Shaw and Geoffrey Bolton argued that Sydney was settled simply as a convict town. They denied that it was originally envisaged in London as a seaport and a possible naval base on the route from England to China and that Norfolk Island far to the north-east of Sydney was seriously seen as a vital source of naval supplies – flax for making sails and rope, and tall straight trees that would serve as strong masts for sailing ships. The controversy was so enticing for Year 12 students, and relatively easy to understand, that it became the most contested debate in Australian history for the best part of twenty years. Meanwhile Professor Alan Frost of La Trobe University, in book after book, did the new research that buttressed my side of the argument and made it more persuasive. But I would say that my side was more persuasive, wouldn’t I? The debate is not yet over.

In 1982 I heard that the phrase was capturing new territory. One day my secretary, Liz Carey, enquired whether I was the coiner of the phrase tyranny of distance. She added that somewhere near the top of the hit parade in England was a pop song performed by the New Zealand group Split Enz and called ‘Six Months in a Leaky Boat’. After singing about the plight of a leaking boat near Cape Horn the group – she explained to me – vividly wailed or sang ‘the tyranny of distance’. A week later, listening to the car radio, I turned by mistake to a pop station. There I heard the male musicians sing, in a haunting way, the phrase I had coined, and soon my daughter was playing the song on a vinyl gramophone record that was slightly scratched. I found out years later that the composer of the hit, Tim Finn, had been reading my book when he wrote his words.

My feeling by the 1990s was that the phrase had already passed its peak. As the World Wide Web arrived, my phrase was seen as outmoded. Rupert Murdoch borrowed it for a major speech that concluded that distance was dead. An English author, Frances Cairncross, wrote an influential book called The Death of Distance which, after explaining courteously that I originated the debate, argued that distance was being conquered by the new communications of the digital age. I accepted her argument that the world had shrunk, but after reading her book I was far from convinced that distance was defeated. Completing in 2001 a new version of my book, labelled the 21st-century edition, I concluded that distance, while tamed, was far from dead.

To the surprise of many historians the United States’ generals and strategists began to emphasise the tyranny of distance, thus reviving my phrase. They knew the heavy additional expense of fighting wars in the Middle East and other regions far from home. To send fighter aircraft to Afghanistan, which lay far from the Americans’ island bases and aircraft carriers in the Indian Ocean, called for aerial tankers that could refuel planes in midair. South Korea, Japan and Taiwan had to be defended, if necessary, by the United States, but they were far from the large American naval bases. In an international crisis there would be perilous delays if, at short notice, American aircraft carriers had to be sent from San Francisco and Pearl Harbor all the way to East Asia.

When a rejuvenated China began to confront the United States’ forces during the first decade of this century, the ‘tyranny of distance’ was a key concern. Nowhere was the phrase used more often than in the island of Guam, the United States territory that lay closest to the South China Sea. Slightly smaller than Singapore it was being converted into a major fortress and naval and air base. During the North Korean missile crisis of 2018, President Trump expressed concern that even this island, if used by the heaviest US bombers, was almost too far away from continental United States. In flying time it was at least five hours distant from the Korean peninsula. The tyranny of distance still prevailed.

In the history of warfare, a succession of bold ideas and weapons had promised to curb the tyranny of distance. The horse and the cavalry had revolutionised warfare and tamed distance; but the Boer War, where more than 300,000 horses were killed in the fighting, foreshadowed the declining role of the horse. In the First World War the flimsy aircraft flourished high above the trenches without seeming likely to conquer distance; and yet in the Second World War the Japanese launched their devastating aerial attack on Pearl Harbor in 1941, and the huge American aircraft dropped the first atomic bombs on two distant Japanese cities in 1945. In various other phases of the war, however, distance was still a powerful obstacle. In the following decades the latest American and Soviet missiles covered vast distances, but many military leaders in the nuclear era believed that ‘the tyranny of distance’ was far from ended.