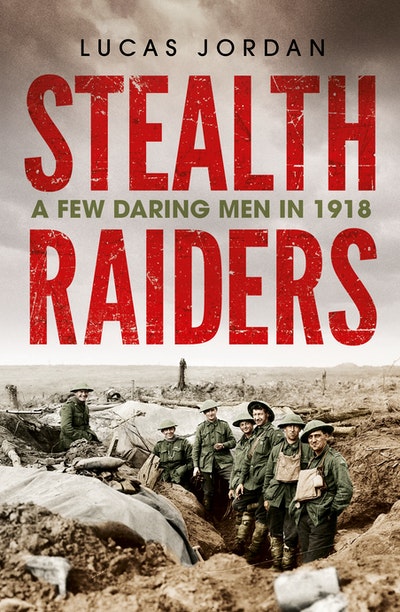

Audacity reigned supreme for some skilled Australian infantrymen on the Western Front.

In Stealth Raiders, Lucas Jordan reveals how the unauthorised actions of a handful of Australian soldiers on the Western Front in 1918 had enormous impacts on the Allied advance. Using firsthand accounts along with archival information and personal records, Jordan pieces together a gripping narrative of bravado, skill and initiative. But what exactly constituted a ‘stealth raid’? And what compelled these soldiers to take the war into their own hands? Here Jordan introduces the circumstances that germinated this uniquely Australian phenomenon.

The enduring images of the First World War are of trenches, barbed wire, machine guns, shellfire and mud, images intimately connected with the battles of the Somme in 1916 and Flanders in 1917. But the German offensives of March and April 1918 swept through the old Somme and Flanders battlefields into farmland untouched by the war. In the late spring and early summer of 1918 the Australian Imperial Force (AIF) fought in a landscape of ‘marvellous beauty’, among fields of freshly sown crops and pleasantly undulating terrain and, in French Flanders, hedges and farm buildings.1 So open was the front that neither side knew where enemy posts were, and there were no continuous lines of trenches. This was not the war that the men had become used to. The strategic situation also was unprecedented; in 1916 and 1917 Australian infantrymen were used as assault troops in offensive battles, but from April to July 1918 the British Army, including the AIF, expected the Germans would attack.

In the fields of the Somme, and at Hazebrouck, 60 miles to the north, where the Australians met the German advance, tired and weary men revelled in nature. Red poppies and brilliant blue cornflowers were in bloom; hares and rabbits were seen frequently; the great game bird of the French farmers, the pheasant, was laying its eggs in the fields; and the grating call of the corncrake was constant at night. The old Flemish and French farmers carrying shotguns over one arm, accompanied by grandsons thumbing cartridges, were gone. Many Australian country boys commented on the great shame it was that these old men and their womenfolk would not be around to harvest what looked like a bumper crop. Corporal Thomas Quinn, a farmer from Mount Bryan in South Australia, wrote:

My Dear People… The weather is still very nice & there are some nice crops about the country we are fighting in. I have seen some crops in no-mans land that I would like to try a binder in, but it would be rather unhealthy there just at present.2

The sun was warmer every day and the hours of daylight longer, increasing the growth of the crop and making the front line humid and sleepy, interrupted occasionally by gusting winds and rain.

In these conditions a few daring low-ranking Australian infantrymen, alone among all the armies on the Western Front, initiated stealth raids without orders. Sergeant John Rafferty, 11th Battalion, wrote:

a stealth raid is made up on the spot by a group of determined men… Patrols might report enemy post in front and you decide with the arms you have in the front line to take it.3

Men of skill would creep up on their enemy, keeping him in their line of sight without leaving cover. Here the personal characteristics of intelligence, ingenuity and daring were combined with professional competence: the ability to employ the full range of weapons at the disposal of the platoon, and in many instances a bushman’s skill to navigate crops, rivers, streams and gullies, to attack and then swiftly return to their posts. This was not what any infantry had done in 1916–1917, and it was unique in the British Army then and for months ahead. Precept had it that higher command ordered setpiece battles, while brigade or divisional headquarters ordered trench raids; these were often planned for weeks beforehand, and provided there was time, the men tasked with the job would be taken back to the rear and trained on ground similar to that they would have to go over. Battalion commanders, headquartered in the front line, also organised fighting patrols, typically consisting of an officer, 20 men and a Lewis gun: a light machine gun, weighing 28 pounds, with a distinctive barrel-cooling shroud and top-mounted pan magazine, which was the heaviest weapon carried by a platoon. These ‘formal operations’, such as setpiece battles and trench raids, might be supported by artillery, trench mortar, heavy machine guns and sometimes gas.4 Yet in the period covered in this book – from 13 April 1918, when all five Australian divisions were committed against the German offensives, to 18 September 1918, as the Australians made their penultimate advance in the Aisne – a few daring Australians attacked enemy posts without orders, often in daylight and with only the weapons in their posts, and from July 1918 onwards schooled others in the British Army in their methods. In this book I call these men stealth raiders.