We caught up with James Bradley to learn about his research process, approach to non-fiction and the unique structure that guides readers through a journey into our oceans.

What inspired your initial research for Deep Water? How did you start that process, and what kicked it off?

The book has a long history. I started thinking about it probably twenty years ago, and I couldn't work out how to write it. There's a tension between writing about such a large-scale subject and not writing a book that is exhaustive.

I spent twenty years learning the things that I needed to know to write Deep Water, so I wrote a lot of non-fiction, did a lot of reading and researched (in some form or another) until I got to a point where I felt like I had enough of the pieces to start.

There were huge amounts of information I just had to go away and learn about, but by the time I began writing, I had enough of the building blocks in place that I had assembled over time – though I did have to start over about three times!

You’ve done a lot of writing before this, but it seems like the scope for writing this book would have been massive. How did you decide what to include and what to leave out?

One of the biggest challenges was convincing myself I had the authority to write a book of this sort. Getting to a point where I felt I had enough command of the material to begin writing took a huge amount of work.

From the beginning, I wanted to write a book that was a kind of hybrid, so I pulled together all kinds of different ideas, ways of thinking, and ways of talking about things. That was very liberating, because it allowed me to pull together all kinds of material – science, history, literature, even memoir – and combine them so they revealed things about each other or opened up new possibilities.

I also let the material guide me, though. Sometimes that meant going off on tangents, but often those tangents led to interesting places. And I tended to use my own fascination as a way to gauge what other people would find interesting – basically I assume that if I thought something was amazing or wondrous other people probably would as well.

You also have a background in writing fiction. Do you think that shaped Deep Water in any way?

Some of the techniques that I learned in writing fiction absolutely come across.

Having come to writing nonfiction from fiction writing, I'm always interested in non-fiction that is emotional.

I like non-fiction that tries to do more than just give you facts and stories. I want to find something in that story that's meaningful. I want to help the reader engage with the subject, and I think emotion is one of the ways you do that.

This book has a really interesting structure. Can you share a bit about that?

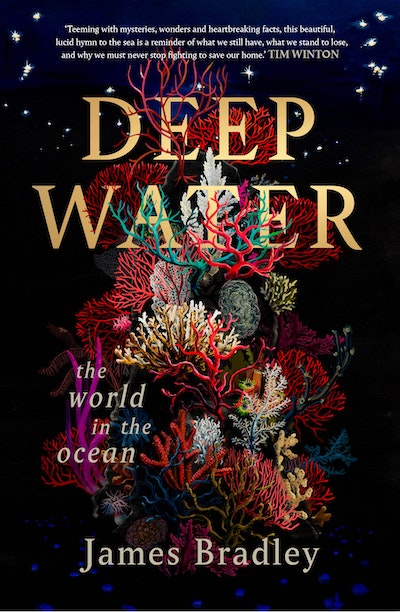

I wanted the book to feel expansive in the same way the ocean is expensive, but I didn't want it to be a collection of essays.

The really tricky task with Deep Water was to find an internal structure that I could bring to bear on the material. That structure is partly intellectual, partly thematic, and I don't think it's necessarily visible. You don't notice it as you go along, but it's there.

Most of all, I wanted Deep Water to feel fluid, and I wanted it to be engaging and accessible.

I was also pleased the first review that came out mentioned that all the chapters have one-word titles except the first, which is ‘The Word for World is Ocean’. It’s a reference to The Word for World is Forest, by Ursula Le Guin, and I was glad that someone noticed that detail because it was really deliberate.

After talking to all these different experts while researching and writing Deep Water, do you have any hope for our ecological future, or is it all feeling pretty bleak?

The thing that I kept coming back to when talking to scientists and others is that hope is not a passive state, it’s a practice. People find ways to keep working even when things look difficult by doing things that will make a difference. In other words hope is an intellectual and emotional practice that arises out of investing in the future, and by working to save what you can or to make the future better. The fact you can’t fix everything doesn’t mean you can’t change anything. The reality is that things only change because people work together and support each other to make them change.