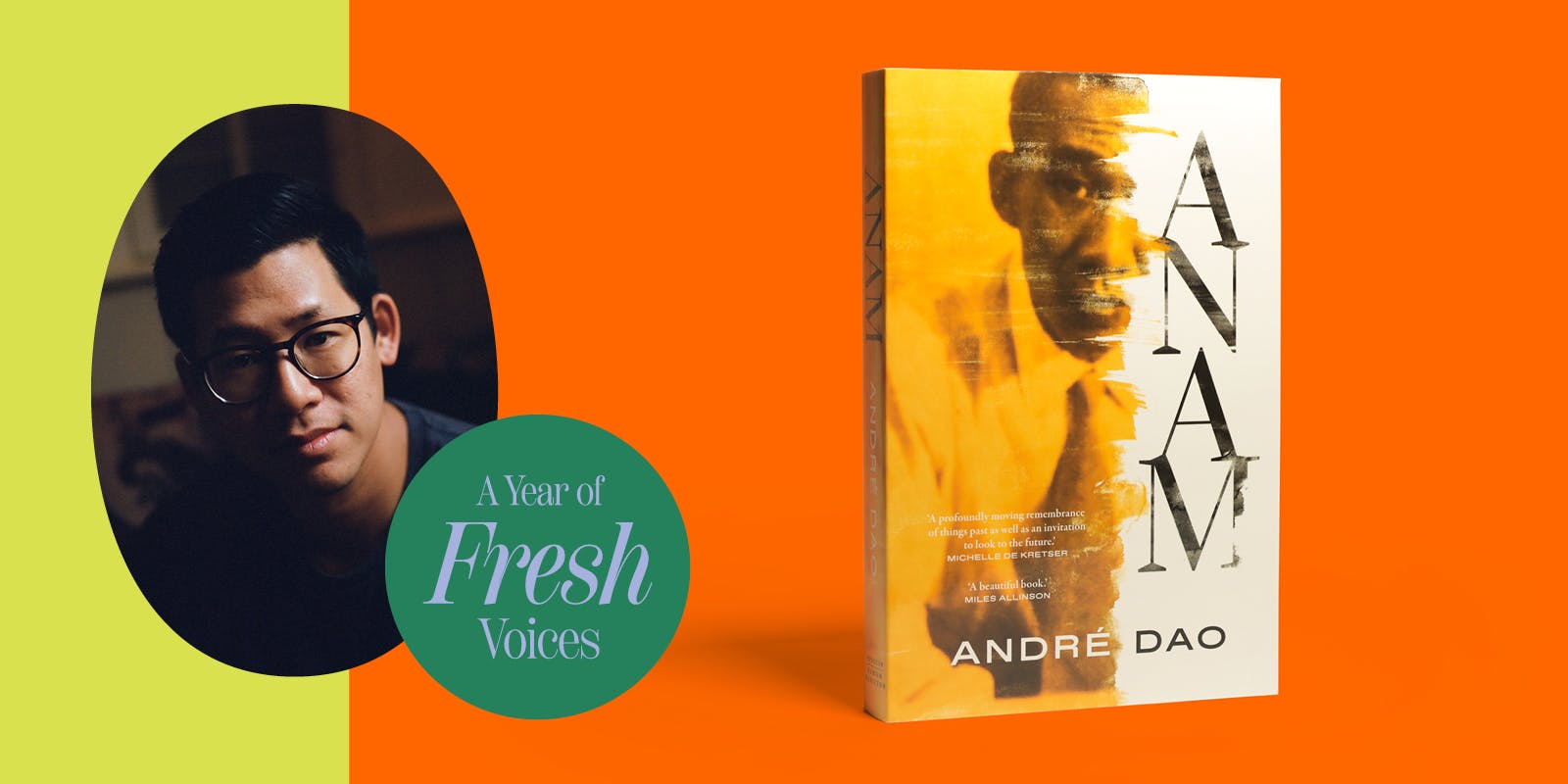

The debut author talks about his writing process and how reading inspired him to become a writer.

What was your writing process like for Anam. Did you have a writing routine or any regular rituals?

I started working on a version of Anam over a decade ago, and in that time my writing process has changed immensely. But there was one routine that helped me complete a full draft around the time that I decided to make the novel more autofictional. At the time, I was studying and our daughter was six months old, meaning time and (mental) space to write were scarce. So I committed to writing for a minimum of ten minutes a day, using pen and paper. Sometimes I could barely get to the ten-minute mark – I would be checking my watch and it seemed as if time had barely moved. On other days, the ten minutes would become thirty, an hour would pass and the words would be flowing. By the end of the academic year, doing this every day, I had more or less a full manuscript.

How did you first come up with the idea for the book?

The novel is based on the lives of my grandparents, especially my grandfather, who was a political prisoner in Vietnam for a decade. So in a general sense, the idea for the book came when I first started to learn, in a fragmented, non-linear way, this family story. The idea for this specific version of the book – a novel that is narrated by a Vietnamese-Australian writer who shares many of my biographical details – came as a kind of solution to the many failed drafts I wrote over the years of that story.

What was your big break into publishing?

I think winning the Victorian Premier’s Literary Award for an Unpublished Manuscript changed everything for me. Up until that point, I had thought of this book as really being quite niche – I hadn’t realised or perhaps hadn’t allowed myself to hope, that it might find a wider audience.

How long have you been working on this book?

I guess it depends on which version of ‘this’ book we’re talking about, and what we mean by ‘working’. I started writing this final version of the book – as an autofictional novel – about six years ago. But I first started writing down bits of my grandfather’s story around 12 years ago, when I started to interview both him and my grandmother about their lives. And then, before that – I have been thinking about this story, and how to tell it, my whole adult life since I first came across the Amnesty International newsletter adopting my grandfather as a ‘prisoner of conscience’.

What was the publishing process like (finding an agent, submitting manuscripts, etc.)?

As I said, winning the VPLA prize made a huge difference – my agent, Clare Forster at Curtis Brown, got in touch when I was shortlisted, and from there it was Clare, and the UK-based Karolina Sutton, who championed the manuscript with publishers. That was very validating, and a huge relief, to have such talented and experienced people in my corner, who knew exactly who was most likely to respond positively to my book.

What most excites you about your book being published in 2023?

I think the public conversation about race, colonialism and literature has changed a lot since I first started putting this story on the page over ten years ago. A big part of that is the emergence of collectives and organisations like Liminal Magazine, and the many younger writers from diverse backgrounds producing politically committed, imaginatively innovative work. It makes me hopeful about the kind of discussion that Anam might be able to generate in 2023.

Do you have a favourite book or author?

I could never name one book or author. Even narrowing down to formative influences on Anam leaves too many – though E.L. Doctorow’s The Book of Daniel was always a kind of model for what I was hoping to achieve. Latterly, Brian Castro’s Shanghai Dancing was important to me, while Alexis Wright’s Carpentaria inspired me to take imaginative risks. This also brings me to Viet Thanh Nguyen’s The Sympathizer. Then there’s Maria Tumarkin’s Axiomatic, Arundhati Roy, and the writings of Jacques Derrida . . . like I said, too many to name!

What inspired you to become a writer?

Reading. I can’t retain what I read – or even really understand what I’ve read – until I’ve written about it.

What surprised you most about the publishing process?

My partner, and first reader, Catherine McInnis, is an editor. So along with being responsible for sharpening my prose over the last twelve years, she has also forewarned me about the publishing process – so, thanks to her, no surprises.

What did you want to be when you grew up and why?

A lawyer, like my grandfather. Or a writer.

If you could go back in time and give your past self one piece of advice, what would it be and why?

Early on in the process of writing this book, I met with a couple of editors who encouraged me to write this story as a fairly straightforward memoir. One of them even said that they expected it shouldn’t take me more than six months! For a long time, their advice got in the way of my writing – I was too focused on what I imagined they wanted me to write. So if I could go back, I’d tell myself to take such advice lightly – so, in a way, to mitigate my previous tip about finding literary communities by saying that as essential as meeting others and speaking with them has been, writing a novel has also necessarily been a lonely pursuit. I had to find my novelistic voice for myself.

What is the best writing lesson/tip you ever received?

That some things – perhaps all the important things – take us ten years to digest before we can write (well) about them. (Credit here to my friend Ellena Savage).