- Published: 16 July 2019

- ISBN: 9780143795957

- Imprint: Viking

- Format: Trade Paperback

- Pages: 272

- RRP: $29.99

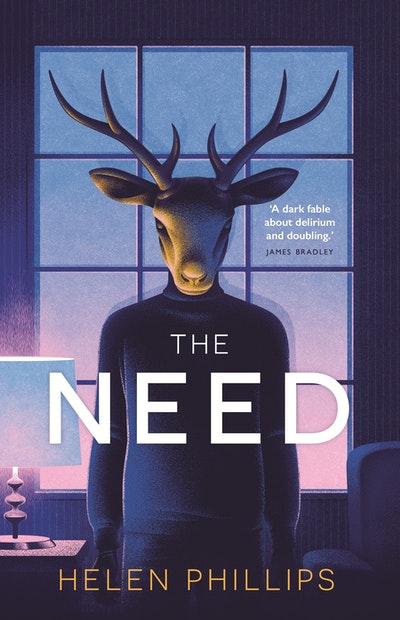

The Need

Extract

1

She crouched in front of the mirror in the dark, clinging to them. The baby in her right arm, the child in her left.

There were footsteps in the other room.

She had heard them an instant ago. She had switched off the light, scooped up her son, pulled her daughter across the bedroom to hide in the far corner.

She had heard footsteps.

But she was sometimes hearing things. A passing ambulance mistaken for Ben’s nighttime wail. The moaning hinges of the bathroom cabinet mistaken for Viv’s impatient pre-tantrum sigh.

Her heart and blood were loud. She needed them to not be so loud.

Another step.

Or was it a soft hiccup from Ben? Or was it her own knee joint cracking beneath thirty-six pounds of Viv?

She guessed the intruder was in the middle of the living room now, halfway to the bedroom.

She knew there was no intruder.

Viv smiled at her in the feeble light of the faraway streetlamp. Viv always craved games that were slightly frightening. Any second now, she would demand the next move in this wondrous new one.

Her desperation for her children’s silence manifested as a suffocating force, the desire for a pillow, a pair of thick socks, anything she could shove into them to perfect their muteness and save their lives.

Another step. Hesitant, but undeniable.

Or maybe not.

Ben was drowsy, tranquil, his thumb in his mouth.

Viv was looking at her with curious, cunning eyes.

David was on a plane somewhere over another continent.

The babysitter had marched off to get a Friday-night beer with her girls.

Could she squeeze the children under the bed and go out to confront the intruder on her own? Could she press them into the closet, keep them safe among her shoes?

Her phone was in the other room, in her bag, dropped and forgotten by the front door when she arrived home from work twenty-five minutes ago to a blueberry-stained Ben, to Viv parading through the living room chanting “Birth-Day! Birth-Day!” with an uncapped purple marker held aloft in her right hand like the Statue of Liberty’s torch.

“Viv!” she had roared when the marker grazed the white wall of the hallway as her daughter ran toward her. But to no avail: a purple scar to join the others, the green crayon, the red pencil.

A Friday-night beer with my girls.

How exotic, she had thought distantly, handing over the wad of cash. Erika was twenty-three, and buoyant, and brave. She had wanted, above all else, someone brave to look after the children.

“Now what?” Viv said, starting to strain against her arm. Thankfully, a stage whisper rather than a shriek.

But even so the footsteps shifted direction, toward the bedroom.

If David were home, in the basement, practicing, she would be stomping their code on the floor, five times for Come up right this second, usually because both kids needed everything from her at once.

A step, a step?

This problem of hers had begun about four years ago, soon after Viv’s birth. She confessed it only to David, wanting to know if he ever experienced the same sensation, trying and failing to capture it in words: the minor disorientations that sometimes plagued her, the small errors of eyes and ears. The conviction that the rumble underfoot was due to an earthquake rather than a garbage truck. The conviction that there was something somehow off about a piece of litter found amid the fossils in the Pit at work. A brief flash or dizziness that, for a millisecond, caused reality to shimmer or waver or disintegrate slightly. In those instants, her best recourse was to steady her body against something solid—David, if he happened to be nearby, or a table, a tree, or the dirt wall of the Pit—until the world resettled into known patterns and she could once more move invincible, unshakable, through her day.

Yes, David said whenever she brought it up; he knew what she meant, kind of. His diagnosis: sleep deprivation and/or dehydration.

Viv squirmed out of her grasp. She was a slippery kid, and, with only one arm free, there was no way Molly could prevent her daughter’s escape.

“Stay. Right. Here,” she mouthed with all the intensity she could infuse into a voiceless command.

But Viv tiptoed theatrically toward the bedroom door, which was open just a crack, and grinned back at her mother, the grin turned grimace by the eerie light of the streetlamp.

Molly didn’t know whether to move or stay put. Any quick

action—a hurl across the room, a seizure of the T-shirt—was sure to unleash a scream or a laugh from Viv, was sure to disrupt Ben, lulled nearly to sleep by the panicked bouncing of Molly’s arm.

Viv pulled the door open.

Molly had never before noticed that the bedroom door squeaked, a sound that now seemed intolerably loud.

It would be so funny to tell David about this when he landed.

I turned off the light and made the kids hide in the corner of the bedroom. I was totally petrified. And it was nothing!

Beneath the hilarity would lie her secret concern about this little problem of hers. But their laughter would neutralize it, almost.

She listened hard for the footsteps. There were none.

She stood up. She raised Ben’s limp, snoozing body to her chest. She flicked the light back on. The room looked warm. Orderly. The gray quilt tucked tight at the corners. She would make mac and cheese. She would thaw some peas. She stepped toward the doorway, where Viv stood still, peering out.

“Who’s that guy?” Viv said.

2

Eight hours before she heard the footsteps in the other room, she was at the Phillips 66 fossil quarry, at the bottom of the Pit, chiseling away at the grayish rock.

She had been looking forward to it, an hour alone in the Pit, the absorption into the endless quest for fossils, the stark solitude of it, thirty yards removed from the defunct gas station, away from the ever-increasing hubbub about the Bible, away from the phone calls and emails and hate mail, away from the impatient reporters and scornful hoaxers and zealots swiftly emerging from the woodwork.

“Almost a decade of mind-bending plant-fossil finds, a bunch of them unplaceable based on our current understanding of the fossil record,” Corey had griped last week, “and no one but us and a handful of other paleobotany dorks gave a damn about this site until now.”

As Molly stood in the Pit, her focus eluded her, the obsessive focus that had been the trademark of her working life, the longtime source of mockery and admiration from her colleagues and her husband alike. Your freak focus, David called it.

Now, though, she was just outrageously tired: soggy logic, fuzzy vision. It was inconceivable that in forty-five minutes she would be standing in front of a tour group, saying things.

The night prior, Ben had awoken every hour or so to howl for a few moments before dropping back into silence. Again and again she almost went to him. Finally, at 3:34 a.m., she entered the children’s room to find him standing naked in the crib, gripping the wooden bars. He had somehow managed to remove his red footed pajamas by himself, a skill she would have guessed was still months off. When he saw her, he stopped shrieking and smiled proudly.

“Good for you,” she whispered, nauseated with exhaustion.

She lifted him out of the crib, anxious about the possibility of waking Viv, and sank down into the rocking chair to nurse him. She shouldn’t do it. It was bad for his freshly grown teeth to have milk on them at night. He was too old for night nursing. But in the dark, disoriented, she sometimes gave in, less to his nagging and more to her own desire to hold a person close and, effortlessly, give him what he most wanted.

Yet tonight, for the first time ever, he didn’t want to nurse. Instead, he pressed his head against her clavicle and then patted her cheek four times before leaning away from her, leaning back toward the crib.

“Shouldn’t we put your pajamas on?”

He was woozy, though, already almost asleep again, and anyway the radiator was going too strong for this uncannily warm early spring, so she returned him to the crib in just his diaper.

She had finally fallen back to sleep in her own bed when there

was a mouth an inch from her face.

“I’m carrying a tree.”

“What?”

“I’m carrying a tree.”

“You’re carrying a tree?”

“No! Not a tree, a dream!”

“You’re carrying a dream?”

“No! I-HAD-A-SCARY-DREAM.”

She and David had a running joke about how they both feared their kids at night the same way that, as children, they’d feared monsters under the bed. Beasts that would rise up from the side of your bed, seize you with sharp nails and demand things of you.

She shouldn’t do it, but she did: hauled Viv into bed, parked the kid between her body and David’s, which slumbered through everything, even through Viv’s sleep dance, her spread eagle evolving into pirouette evolving into breaststroke, her almost-four years swelling to take up far more space in the bed than their combined sixty-eight.

So you wake up ill with tiredness but it’s your own fault for not being better, stricter. So you stand there at work wondering what you have to offer the world, just your strained, drained body and your weakness. But somehow you crouch down again, again you hack at the unyielding earth.

And that was when she saw it.

That unmistakable brightness, the warm color of childhood, a wish in water.

A penny, lodged deep in the dirt at the bottom of the Pit.

A new penny, that glow of the recently minted.

So, the most current artifact of the five to date: the Coca-Cola bottle, the toy soldier, the Altoids tin, the potsherd, the Bible. Her strange discoveries had taken place gradually, over the course of the past nine months, starting with the Coca-Cola bottle her first week back at work after Ben’s birth (she had picked it up, tilted her head this way and that, trying to figure out whether the oddity lay in her or in the font). Just the tiniest dribble of random objects amid the tsunami of plant fossils. But, here, another find, only a month after the Bible.

As she photographed the penny and recorded its GPS coordinates (hoping her own stupid footsteps hadn’t already altered its location), adrenaline blasted through her fatigue. She ought to leave it in situ and call Shaina to find out how soon she could drive across town to come take a look. Shaina was the first person Molly had contacted when she found the Coca-Cola bottle, needing the archaeologist perspective from her old grad-school friend. But from the start Shaina had taken a dubious stance on the objects: she complained that Molly and Corey and Roz, all with their typical paleobotanist’s disregard for the maintenance of the stratigraphy, had long ago made any meaningful archaeological analysis very nearly impossible. “You work by way of sledgehammer,” Shaina had said. “I work by way of sieve.”

“But you think the Bible was really printed in the early 1900s?”

“Look,” Shaina had said over beers at the nearest bar, “for all I know, some high-tech prankster buried that Bible in the Pit hours before you uncovered it.”

“And the others?” Molly pressed.

“Same. Sure, like, with the potsherd: yes, interesting, it’s not a pattern I’ve ever seen before. But it’s so small, and with no organic material found nearby that I could use to confidently carbon-date it . . . Yes, sure, I’m weirded out by an old Altoids tin that’s slightly the wrong shape. Yes, I’d like to identify somewhere, sometime, another plastic toy soldier that was manufactured with a monkey tail. I’ll study them a bit more because I can tell you care a lot. But there’s just not really enough to work with.”

The penny glinted up at Molly. She and it, alone together. This was what had drawn her to a field that involved unveiling the layers of the earth, unsure what you were seeking: this throb of fascination. She used the tip of her trowel to dislodge the penny.

“Excuse me,” she said to the penny as she pried it out. Minted this year, she noted as she slid it into a baggie from her pocket. She would postpone any further examination until she was back in the lab. She wanted to pause here, between not-knowing and knowing. She looked up: above her, beyond the twenty-foot walls of the Pit, the sky was the color of milk.

3

She had no choice but to look out into the living room herself.

What could she do to make sure he would shoot her and spare the children?

“Did you really see a man?” she whispered.

Viv smiled up at her.

“Move,” Molly said, trying to scoot her daughter out of the doorway with her hip.

But Viv, sensing her mother’s urgency, tensed her muscles and refused to budge.

“Viv,” she said, suddenly nonchalant, “go on out to the living room. I’m putting B down on my bed and you can’t bother him while he sleeps.”

That was all it took. Viv let go of the doorjamb, jumped onto the bed beside her brother, began harassing him with coos and kisses.

The ploy bought Molly perhaps forty-five seconds before the baby woke or the big sister tired of the provocation. She hurried to the doorway. A peculiar half laugh rose in her: hurrying to see who had broken into their home, just as she was always hurrying to get ready for work, hurrying to put the groceries away, hurrying to take a shit, every single thing in life shoved between the needs of a pair of people who weighed a cumulative fifty-seven pounds.

Who’s that guy?

But as she looked out at the living room, she saw only its normal end-of-day chaos, a scattering of Cheerios, a ruin of blocks, the crayons splayed like many fingers pointing. Usually the sight would have wearied her, but at this moment, colored by her relief, it seemed terribly beautiful.

It was an open, spare room—no place to hide. Just couch, bookshelves, chairs, dining table. The only possible hiding spot—as she’d learned last month when, for an entire weekend, Viv refused to do anything except play hide-and-seek—was inside the squat, ugly coffee table that doubled as an enormous toy box. It had been so coffin-like in there that she had begun to miss them fiercely when she heard their voices, their footsteps (David’s surprisingly heavy for such a skinny man; Viv’s quick, frantic; Ben’s so dainty, halting and sticky), moving through the rooms as they searched for her. But no casual intruder would realize the coffee table was hollow inside.

Everything was fine, fine, fine.

She strode to the kitchen. Turned on the overhead. Opened the freezer to pull out the peas.

In the bedroom, Viv screamed.

4

Her makeshift office was at the back of the gas-station-turned-research-lab-and-display-room, in what had once been the candy aisle of the Phillips 66. She pulled her wallet from her bag, unzipped the overstuffed change purse, was lucky enough to find a penny also minted in the current year.

She placed the penny from her wallet on an examination tray. She had never in her life looked so closely at a penny. The phone on her desk was ringing but she ignored it. She tugged open the plastic baggie, shook the penny from the Pit out onto the examination tray along with a sprinkle of Pit dust, and wrote beneath the penny on the left CONTROL and beneath the one on the right PIT.

What would it be this time? A president other than Lincoln? Or the profile of a leader unknown to her? The word PEACE or ORDER rather than the word LIBERTY? A sunburst instead of a shield? An alphabet she didn’t recognize? Or, more likely, some subtle shift of typography or proportion barely perceptible even to her eye trained in tracing the faintest veins of ancient leaves.

Just then her milk came down. It often came at moments of high emotion. That slight ache or buzz, valves pressured into opening, the simultaneous relief and frustration, her bra damp in two focused spots. Reminder: Mother. Reminder: Animal.

Her breast pump was somewhere in the darkness beneath the old metal desk. When had she last rinsed the shields and the valves? It was a hassle to clean them. She would need to scrub them before pumping. If she were more on top of things, she would have taken them home to boil them in hot water for five minutes.

But for now: the two pennies, side by side. Mundane and sacred at the same time. She thought of her children.

The penny from the Pit. Heads side: above Lincoln’s profile, the words IN GOD WE TRUST. To the left of his profile, the word LIBERTY. To the right, the current year.

She searched for a difference in Abe’s facial expression; was he perhaps a tad more wry, a tad less stern, in the penny from the Pit?

But eventually she had to admit that the penny from the Pit was identical to the penny from her wallet. The difference would lie, perhaps, on the other side.

Her bra damper by the second.

Because her fingers were quivering, it took two tries before she managed to flip over the coin from her wallet, three tries for the coin from the Pit.

Tails: beneath the declaration UNITED STATES OF AMERICA, a shield emblazoned at the top with the phrase E PLURIBUS UNUM, and, on a banner in front of the shield, the words ONE CENT.

On both, the shields were the same shape, each bearing thirteen stripes. Beneath the shields, the same miniscule LB on the left-hand side and JFM on the right-hand side.

Two identical pennies.

She felt ridiculous. So she or Corey or Roz had accidentally dropped a penny at the bottom of the Pit. So what.

She picked up both pennies and put them in her wallet.

The burden of the milk.

Her fatigue returned like a hand pressing down on her skull.

The Need Helen Phillips

Speculative fiction of the highest calibre: one woman fights to retain her sense of self amidst the chaos of work, motherhood and alternative universes.

Buy now